Review Essay

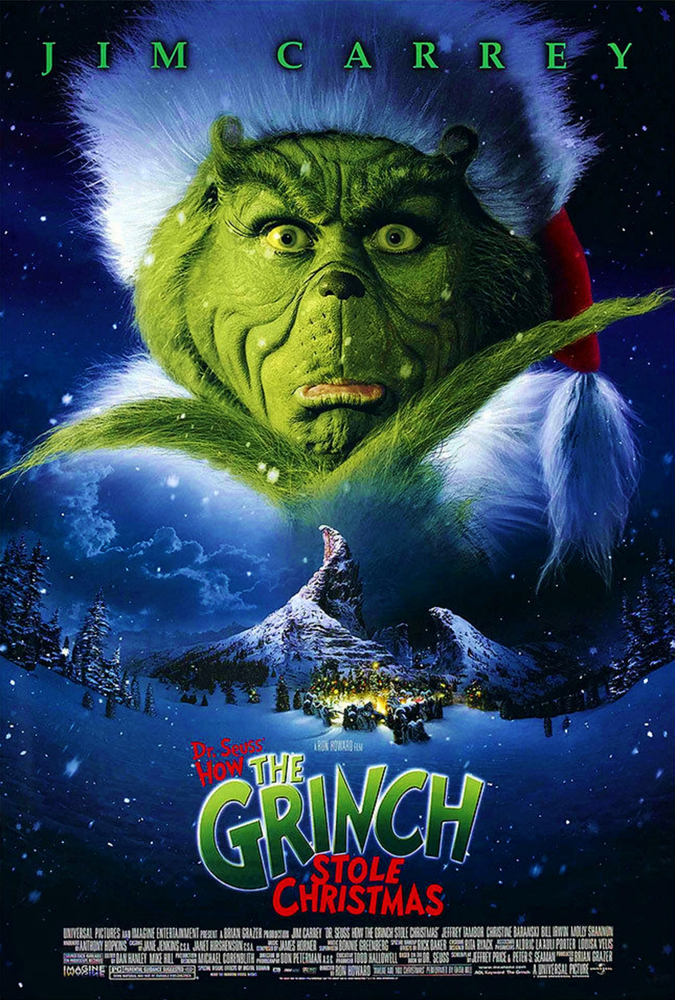

We might as well get this out into the open from the outset: I like the 2000 film, How The Grinch Stole Christmas. That’s a semi-controversial take already: the movie has long had plenty of detractors, and in some circles I’ve seen people make disparaging swipes at movies being “like that Jim Carrey Grinch movie,” as though it was shorthand for a bad holiday flick. But it may not be THAT controversial—the film’s a perennial holiday showing even now, 25 years (!) after it was released, and I think a lot of people have at least moderately fond memories of it. What’s probably going to be a little more startling, though, is my argument that, in fact, I love this movie, and I think it might be one of the best holiday movies ever made. And what will be sacrilege for at least some of you is my argument that it’s a far better film than the 1966 Chuck Jones animated version of Dr. Seuss’s original book, which a couple of generations (mine included) grew up on. It’s how I feel, though, and however hot the take, I’m going to do my best to persuade you that I’m onto something, anyway, even if you aren’t as taken with this movie as I am.

The basic premise of the Grinch tales in all their manifestations—and I’ll acknowledge up front, I’ve not seen the 2018 animated film or the televised Broadway musical, so I’ll have to leave them for some future blog post—is well known to almost anybody in the American cultural sphere. Somewhere in the world of Dr. Seuss’s imagination, there’s a town called Whoville, populated by the Whos, a people about whom all we really know is that they celebrate Christmas with enthusiasm. Neighboring this bucolic village is Mount Crumpit, and on the slopes of that mountain lives a sour, solitary creature called The Grinch, who hates Christmas (and, by extension, Whoville), because his heart is “two sizes too small.” He eventually gets fed up with the sound of holiday festivities and steals all Christmas accoutrements from the homes of the Whos, before his inevitable change of heart. It’s a simple story, fit for a children’s picture book, and I think it works just fine as Seussian spectacle (and as a short animated special). I wasn’t ever really in love with the original, though, I’ll admit: it’s not among my 2-3 favorite Seuss books, and of all the midcentury Christmas specials airing on my family’s TV in my childhood, it was honestly one of the least essential, as far as I was concerned. There just wasn’t much to the story—the animation was stylish and the voice acting was fun, but that’s about as far as it went.

The genius of the 2000 film adaptation, in my opinion, originates in its need to bulk up a very simple story into a feature-length screenplay. As a result, the movie is forced to grapple with the Grinch as a character—why is he the way he is? What’s his history with Christmas, or the Whos? Depth is needed, and the script supplies it. Furthermore, the only Who with any persistent importance in the story from its original book form (Cindy Lou) has to be given a sense of connection to the Grinch also, and here I think it’s managed really successfully. The emotional investment she makes in The Grinch builds something powerful into the movie’s final act. It all matters.

I suspect that one of the reasons the 2000 film takes heat from long-time Grinch fans is that it more or less up-ends the moral landscape of the original story—and in doing so, it puts our society in an unflattering light. But that’s what I love about it. The original tale is a simple one: us nice Christmas-observing nuclear families are the good guys, singing our little songs and having our little feasts. The villain of the piece is the outsider: he does not look like us, he does not celebrate our holiday, and when our innocent celebration has made him angry, he tries to wreck our joy. The fact that we continue to be happy because we have right-sized hearts convicts him at the last possible moment, so that he can repent and be integrated into the Christmas celebration. Put it like that, and it doesn’t sound so nice, does it? No offense to Ted Geisel, but it sounds a lot like the kind of pro-conformity message that he is otherwise famous for undermining in stories like “The Sneetches.” The 2000 version, on the other hand, rightly understands that to the extent that there’s a plausible villain in this scenario, it’s the people of Whoville: they’re the ones whose material wealth is overflowing while a solitary creature is isolated outside their community, subsisting on their trash. Their obsession with celebration is so all-consuming that they don’t consider the side effects of it—all the noise, noise, noise, noise!—which would be bad enough if the Grinch was merely someone indifferent to Christmas. But of course it’s more complicated than that: from his youngest days, his experience of Christmas was isolating. The holiday celebrated in Whoville demanded a great deal of cultural conformity that was unhealthy—the Grinch is mocked openly for his differences, and ultimately is driven out of town by bullying and ridicule at a young age. Later, when the sound of the Whobilation’s Yuletide festivities is driving him crazy, the Grinch grabs a hammer to knock himself out with, saying, “Now, to take care of those pesky memories”: he knows that what bothers him here isn’t the noise, it’s the mistreatment that it now represents to him, because of his experience of the Whos. And of course, most of the people of Whoville aren’t evil (their Mayor being the prime exception to the rule). They’re just cheerfully complicit in some pretty cruel abuses out of a desire to remain comfortable and untargeted, themselves—they’ll quietly allow a powerful, arrogant blowhard to stand in public at a microphone, abusing outsiders for his own self-aggrandizement and making up passages from The Book of Who to suit his demented purposes while dismissing the one true believer willing to stand up to him in public and insist that the community’s values are actually imperiled. Yep, if you thought you could escape the politics of 2025 here, I’m afraid I can’t let you. What an incredibly apt movie for the moment.

And yet, what I think is most impressive about this movie is that the Grinch’s critique of the society bordering him is—for a movie in which Jim Carrey is a huge wisecracking green Yeti, essentially—pretty nuanced. In a crucial scene, mid-film, The Grinch is given a triggering Christmas “gift” by the Mayor, in front of the whole town: it’s a reminder of the Grinch’s trauma, and the gathering treats it as a chuckle-inducing anecdote. Remember that day where we made fun of you so badly that you fled into the mountains to live as a hermit….when you were, like, 8 years old? Kids do the darnedest stuff, don’t they? (I’m telling you, this film is wiser than it has any right to be about how “good” people do bad things.) Anyway, you’d expect the guy to blow up in that moment: this is personal, it’s painful, and he could say so. But he doesn’t confront Whoville until their town’s materialism is the thing on display, because I think on some level, the Grinch understands that that’s the real problem. A society that’s more focused on the superficial, on presents and costumes and conspicuous consumption, is a society that loses touch with its own heart. He doesn’t tell them it’s what leads them to hurt an outsider like him. He doesn’t believe in their capacity to understand that truth, really—he has no faith in the Whos, and they’ve done little to deserve such faith, in any case. This is what makes the triumph at the end of the story something powerful—it’s not just some mountain gremlin returning everyone’s Christmas ornaments so they can have the party they’d been planning on. The Grinch comes back to them because they showed him that something he didn’t believe in was real—that this community could learn to find more joy in each other as people (him included) than they ever had in their stacks of Christmas presents. He apologizes to them for how he’s behaved because they’ve earned his trust on a level he never imagined.

And yes, I know, I’m talking in soaring thematic terms about the ethical messages of a movie primarily intended to give us Jim Carrey making a fool of himself on screen. Well, look, Jim’s not for everybody (and I don’t feel a ton of affection for some of his wildest comedic performances), but to me putting his manic energy inside this huge green fur suit is a match made in heaven. My wife and I can (and do) quote half his lines all year long, from “Nice kid…. Baaaaaad judge of character.” to “One man’s toxic sludge is another man’s potpourri!” to “Oh no….I’m speaking in RHYME.” I can imagine, of course, responding negatively to some of Carrey’s antics, but I just think it works for the character—it lightens what might otherwise be too heavy a story, honestly, to have the Grinch be someone who’s responded to being ostracized by becoming a standup comedian, transmuting his pain into a PG-friendly Don Rickles routine.

The other thing that gives this movie its needed heart is the performance by Taylor Momsen as Cindy Lou Who—sure, the character is earnestness personified, but that’s her dramatic function. What I appreciate about Cindy Lou, and this only increases with time, is the way she expresses something far more mature than a child performance normally would. This Cindy Lou is not merely some little kid woken up by the Grinch’s theft, as she is in the original. She’s someone wrestling with the question of why Christmas doesn’t feel the way it used to—asking herself what the magic was, and where it’s gone. This is not, I acknowledge, something an elementary schooler would normally feel. But speaking as a kid who was a melancholy elementary schooler (somewhere I still have the Last Will and Testament I wrote at the age of about nine), it tracks. More than that, though, what Cindy’s wrestling with is what we all wrestle with, no matter what holidays we do or don’t celebrate: where does our capacity for that childhood sense of wonder and delight go? Is it just nostalgia for something that never existed and we’re smart enough to see that now, or was it real and we can find it again? Given all that, it’s a really lovely (and touching) message that Cindy discovers that we can have that holiday happiness again, but only if we get our heads on correctly about what the holiday’s actually about. We can’t find the joy in ever-increasing material consumption—the joy isn’t there. It’s in the hearts of people who see and hear each other, of people who not only have the capacity to love but who put that capacity to work. It’s in a community that, rather than seeing outsiders as threats to their stability, can look at those outsiders through the lens of the values they claim to profess, of welcome and inclusion and care. THAT’S what can leave us singing “Fahoo, fores; dahoo, dores,” hand in hand with our neighbors.

And I think folks forget what high-quality craft goes into this film—Anthony Hopkins’s narration providing a lovely, lyrical insight into the story. Incredible production design, from the costuming and makeup worn by the ridiculous Whos to the junkpunk vibes of the Grinch’s “lair” that’s filled with what are apparently his inventions. A great symphonic score by the always reliable James Horner, and a sentimental song that seems to have stuck around in the Christmas pop canon in “Where Are You, Christmas?” I think the admittedly larger-than-life presence of Jim Carrey in outlandish makeup slinging one-liners leaves people misremembering that that’s all this film has to offer. Again, I know mileage varies. A lot of you won’t get out of the movie what I see here. But if you love it also, well, I hope I’m helping articulate some of the things that we might both be seeing in this film.

I Know That Face: Molly Shannon, who here plays Betty Lou Who (Cindy Lou’s decoration-obsessed mother), is a veteran of seasonal projects: she’s Tracy in The Santa Clause 2, she plays a fictionalized version of herself in It’s a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie, and in 2004’s The Twelve Days of Christmas Eve she plays Angie, a kind of angel who gives the protagonist 12 attempts to get Christmas Eve right (a la Groundhog Day). But she can’t match the even more holiday-infused track record of Christine Baranski, the Grinch’s love interest here as Martha May Whovier—Christine’s playing Regina in 2020’s Christmas on the Square (a Dolly Parton project), she’s Ruth in A Bad Moms Christmas (a comedy I fear I’ll have to review one of these years), and she’s Lee Bellmont in Recipe for a Perfect Christmas. Christine also voices Flo in Timothy Tweedle the First Christmas Elf, and she’s Prunella Stickler in Eloise at Christmastime, and of course as a sitcom regular (on Cybill, as Maryann Thorpe) she appears in Christmas episodes, including season 3’s “A Hell of a Christmas.” I would be remiss if I didn’t take the chance to shine the spotlight on the director’s dad, Rance Howard, who’s Whoville’s “Elderly Timekeeper”—he voices Rudolph in Elf Sparkle and the Special Red Dress, he plays a blind man in Holiday in Your Heart (a LeAnn Rimes vehicle), and back in 1986 he was in his own Dolly Parton project, A Smoky Mountain Christmas, playing Dr. Jennings. Lastly, we have to tip our cap to Jim Carrey, the Grinch himself, who of course got a much more negative review from me when I reviewed his work as nine different people in Disney’s A Christmas Carol.

That Takes Me Back: The whole village is wired in series, so that a single loosened bulb on the Whoville Christmas Tree turns out the lights all over town. It reminded me, for a moment, of having to test every single bulb in the lights on the tree in order to figure out what had gone wrong.

I Understood That Reference: Of course, as the Grinch prepares to deploy his plan to steal Christmas, Santa’s been there ahead of him. In any case, the Grinch is aware of the Rudolph narrative, since he riffs briefly with his dog, Max, about the reindeer’s having saved Christmas.

Holiday Vibes (8/10): Christmas in Whoville obviously both is and is not like Christmas anywhere else: there’s a lot here that “feels holiday” as Cindy Lou’s dad would probably have said, and of course my watching it routinely each December must add to that feeling. To me, the feast and the presents and the decorations certainly create the right kind of feeling…but even more so, the message of love and our capacity to create community together is just what I want to feel at this time of year, and I’m glad it helps me do this.

Actual Quality (9/10): Look, I know this isn’t a flawless masterpiece—any movie where one of the jokes is getting a sleeping man (however odious) to kiss a dog’s butt is definitely not hoping to win any awards. But I also think it absolutely deserves a much better reputation: it takes what is, frankly, a reactionary message about insiders and outsiders in the original tale, and transforms it into a much more thoughtful exploration of ostracism and its consequences. It’s also funny, and sweet, and the whole movie takes place inside of a snowflake, like the one on your sleeve. It’s great in my book, anyway.

Party Mood-Setter? It’s absolutely quotable enough to just be rolling in the background while you do other things, and the story’s cultural saturation is so high that a Grinch on the screen probably won’t be too distracting to party-goers, even though it easily could suck people in.

Plucked Heart Strings? I find some of Cindy Lou’s struggles pretty easy to identify with, but they don’t exactly make me mist up. It’s an effective emotional arc, but I think you probably won’t need to watch the movie with a tissue box next to you.

Recommended Frequency: I’m not sure how to get through a year without watching this one. It’s just too deeply ingrained into my memory (and my wife’s). If you’ve never seen it, or just haven’t in a while, I hope you’ll consider giving it another spin.

This movie is fairly easy to access, though not necessarily for free—you can stream it if you’re a member of Amazon Prime, or Peacock, or Hulu. You can pay to rent it from most of the usual places too, it looks like. Barnes and Noble will sell it to you on disc, and around 1,500 libraries have a copy to check out for free, according to Worldcat.