Review Essay

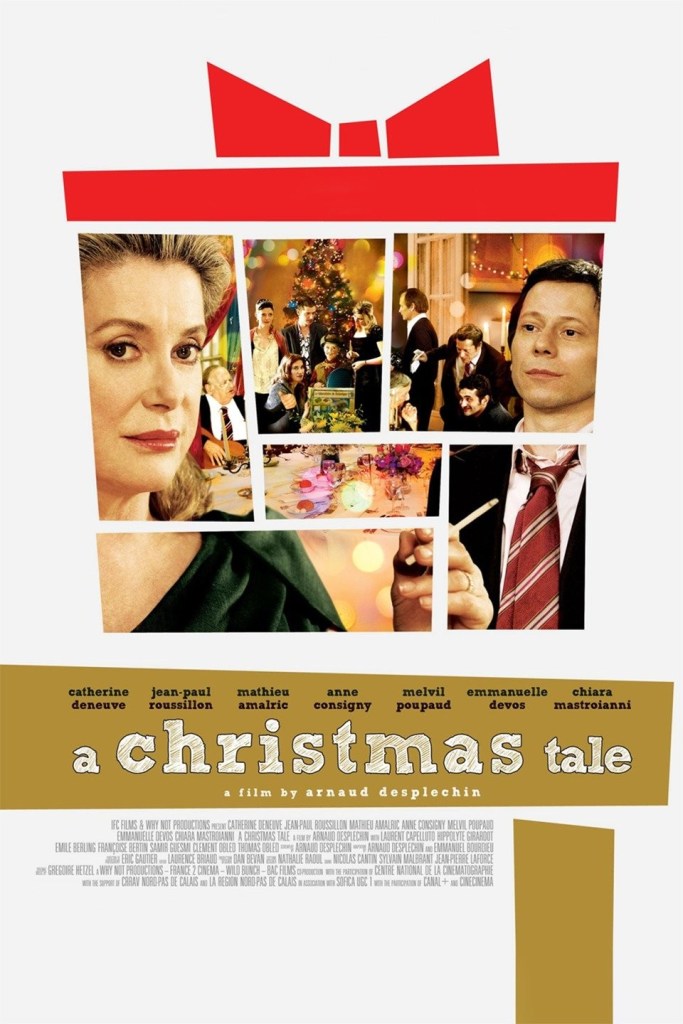

One of my favorite bands—in fact, if I’m thinking about “bands” as opposed to individual musicians, they’re probably my favorite band—is The Mountain Goats, which has been the primary outlet for the remarkable songwriting talents of one John Darnielle for the last three decades plus. I mention TMG for a couple of reasons, as I try to figure out how to tackle 2008’s A Christmas Tale, a very French movie about a dysfunctional (and very French) family gathering on the titular holiday. A good Mountain Goats song often has a lot to say about damage—about what it’s like to be a person who’s been damaged, who carries that damage inside yourself, and about what it’s like to understand your own capacity for damaging others (whether you’re going to explore that capacity actively or not). A good Mountain Goats song also often has a lot to say about love—about love as it is outside of the storybook, where in our real lives love can be as painful as it is pleasant, as catastrophic as it is consoling…how love (in its myriad forms) is the one source of solace in the restlessness of life but also how the itch of love (in those same myriad forms) can sit uncomfortably under our skin in ways we will never be at peace with. A great Mountain Goats song is usually about both love and damage. A Christmas Tale, if it’s working for you, is going to work like a great Mountain Goats song. The position I’m going to have to advance, alas, is that A Christmas Tale never fully works for me, but I at least respect what it’s attempting—art that is aggressive and polarizing and honest about things that might be hard to hear.

The film comes out of the gate like an accidental firearm discharge—an aging French man, Abel, looks at us straight down the barrel of the camera lens, saying “my son is dead,” and follows it up with a eulogy that clarifies that he has no real intention of mourning the six year old they are laying to rest. This is not a movie for the faint of heart. The premise that unfolds thereafter works like so: Joseph, the six year old, died of leukemia after no bone marrow match was found for him. The parents, Abel and Junon, even had an extra son, Henri, in an attempt to “make” a marrow donor, but it didn’t work. Now, decades later, all their surviving kids are grown when a new disaster strikes. Junon is diagnosed with leukemia. And so now, for a second time, as Christmas approaches, the members of this family must be tested to see if any of them are a match (and, if so, will a family this internally divided, this estranged from itself, knit together sufficiently that Junon will be given the gift her son Joseph never received?). If you’re thinking, “James, this sounds BRUTAL, why would you watch this,” friend, we try a little of everything here at FFTH. I wanted to explore another foreign language film this year, and I wanted to see how a Christmas movie tackled genuinely heavy subject matter. If it’s not for you, I hear you, but stick around to at least learn why this film is somehow not always as raw emotionally as you might think.

One reason I don’t think the movie’s quite such a heavy burden, as an audience member, is that I spent a lot less time grieving for these folks than I did staring at them in puzzled wonder. Their emotional registers are so differently calibrated from my own, and the kinds of conduct they condone (and engage in) are often really unexpected. Everyone’s at odds with everyone else, starting with the eldest surviving child, Elizabeth, who’d exiled her brother Henri (yes, “extra” kid, failed marrow donor Henri) from the family years ago in exchange for the money that saved him from ruin, and running all the way to Sylvia, wife to Ivan (the youngest brother—yeah, somehow, after “extra” Henri, Abel and Junon chose to have another kid), a woman who apparently was pursued as an object of potential romantic conquest by at least three members of this extended family and who, spoiler alert, is going to have a dalliance with at least one person she’s not married to before the movie’s over. And if you’re saying, wait, James, surely Sylvia is not knocking boots behind her husband’s back in one of the bedrooms at her in-laws’ house on Christmas Eve, my answers are a) yeah. Yeah, she is. And b) it’s not even clear how much she’s trying to keep things behind her husband’s back. That was one of the many moments I had, while watching this film, in which I shook my head gently and said, “Those French folks….they are different than I am, aren’t they?” Virtually everyone in this family has the capacity to go to battle against just about anybody else on screen, and within three minutes they can be kissing each other on the cheek and looking for another bottle of wine to open and share. The emotional roller coaster doesn’t come to a stop until the end credits roll.

The two most damaged players at the heart of this story are two men who barely know each other at the movie’s start but come to find a weird sense of kinship as it progresses. One of them is the self-destructive, narcissistic rage monster, Henri, who clearly never had the chance to recover from his knowing from the youngest possible age that he was a failed experiment, a child born to rescue the older brother he could not save. Everything about Henri—his addictions, his chaotic love life, his aggressive and cruel demeanor—is completely explicable based on all we know about him and two tragic deaths in his past. His father calls him “Henri Misery” as a nickname, and at one point when Henri asks his mother why she doesn’t love him anymore, she laughs and tells him that she never loved him in the first place. Here’s the thing, though: they all seem drawn to each other regardless of these cruelties, either because they’re a family that does feel a love they can’t put into words, or else because what holds them all together is some force other than love. The other significantly troubled family member is Elizabeth’s son, Paul Dedalus, a teenager with a history of mental health issues who’s been hidden away from Henri due to Elizabeth’s totally broken relationship with her brother. Paul’s having hallucinations, he’s experiencing suicidal ideation, and he’s treated like a fragile china doll by his mother, who expects the family to observe all her rules around keeping him calm and safe. Henri and Paul, of course, are seemingly the only two members of the family who might be fit candidates for the bone marrow transplant, and so fate throws them together with Junon, their mother/grandmother, as the family argues over who should do it if both of them can (or whether either one or both of them will be disqualified for health reasons). One of the film’s more moving if inscrutable sections occurs when, on Christmas Eve, it’s only these three members of the family who decide to walk together to midnight mass, despite none of them having given any indication of interest in religious observance previously.

But I’m drowning in this film, friends—I’ve already written so much and I’ve managed to say so little. I took over a dozen pages of notes while watching this incredibly complicated, layered foreign film and I’m still baffled by half the things I even understood well enough to write. Every possible combination of characters in this family seems to have its own special energy, whether of kinship and affection or of hostility and struggle (usually both). There are unsettling moments and eerily calm ones. At times it feels like a very normal family gathering at the holidays and at times characters speak so mercilessly to each other that you can’t believe they stay under the same roof without one or both of them burning the house down around their ears. Sometimes conversations involve characters discussing things or taking actions based on knowledge I don’t really understand how they came to possess. I probably missed something in the flurry of subtitles, but I think it’s also possible the movie intentionally maintains at least a mildly dreamlike state of ambiguity, where things don’t fit together as neatly as I might have expected.

As I suggested at the outset, I’m just not sure this works, even for me, a guy who’s open to art that explores some pretty complicated feelings. I think it’s one thing for me to try to understand the psyche of a difficult, selfish person in a three minute rock song, and another to watch that person on screen for a couple of hours dealing out unrelentingly vicious commentary at almost everyone he encounters. I can feel compassion for Henri but I also feel trapped in the room with him, and when I feel that way it’s hard not to see his sister’s side of the story. I think the director feels a lot more compassion for the parents than I do—parents who, yes, lost a child young, a horror I hope never to understand—given how appallingly and borderline abusively they’ve conducted themselves towards and around their kids ever since. The film doesn’t seem all that interested in letting the story lead us towards resolution of most of these issues, though, and to the extent that anything gets “resolved” I would say I find the resolutions both implausible and unsatisfying. Sure, in real life, I bet these people would go on damaging themselves and each other, with no real guard rails in place to hold them back. But in real life, I wouldn’t stay at their house for several days at Christmas…heck, I probably wouldn’t pick up the phone when they called. So, why would I watch a movie about them?

And I think that’s the question that you’d have to answer for yourself: could it be that, by watching a deeply dysfunctional French family stumble their way together through the holiday under intense pressure from this urgent medical need, you could maybe process some of your own feelings about both the holiday and your family experiences? Might you gain a better understanding of some difficult people in your life, or be able to reflect on the ways you’ve abused your own power as it relates to those difficult people? I bet some of you could, and certainly the critics who reviewed this film seem to have almost universally found it really powerful and moving. The fact that I wanted that experience and didn’t really get it doesn’t mean that it’s not there to be gotten, after all. I just think that too often the film struck me as a document that wanted to believe in its own profundity more than it ever managed to express something profound. Abel at one point quotes a passage from memory—a passage from the works of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. It’s long and complex, and I can imagine it being rich with meaning, but it’s so out of character for him, and seems so unrelated to the other appearances he makes on screen, that it just felt like a director’s affectation. Affected, too, is the movie’s final moment—an atmospherically lit and shot scene in which a character delivers to camera the final lines spoken by Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. What on earth does Robin Goodfellow or a fairy-laden bucolic comedy have to do with this bitter, wintry French family drama, you might well ask, and that’s sure what I said out loud (I might have raised my voice) at the screen as the end credits rolled. Like, I’ve just told you the final scene in the movie, but if you stopped six minutes before the movie’s end and tried to guess which of the characters it is who speaks these lines, I bet you’d have no more than a 1 in 10 chance of getting it right, it’s that random. But I guess it’s “literary” or something. Anyway, it’s a challenging European art film, with some gruesome medical imagery, frank talk about death, and a little graphic sex—all of those things felt organic to the story, so I’m not complaining about anything being sensationalistic, etc., but I figure it’s good for you to know going in that for a movie called “A Christmas Tale” very little of it will be light-hearted or magical. Some smart folks have gotten a lot out of it, though, and if you try it yourself, I hope you do too.

I Know That Face: Anne Consigny, who plays the rigid daughter Elizabeth here, appears as Suzy Elisabeth in 2017’s Let It Snow, which is not to be confused with the 2019 Let It Snow that I reviewed three days ago. And Emmanuelle Devos, who here is Henri’s buxom Jewish girlfriend Faunia, who ducks out of the Christmas celebration to go and not celebrate Hanukkah with her own dysfunctional family, shows up as Beatrice Barand in 2023’s Noël joyeux.

That Takes Me Back: At one point we see family members getting wood from outside and moving it into the house for the fireplace, which was a regular nightly duty as a kid in the wintertime, for me. I’m happy not to have a wood stove any longer, but there are things I miss about it, and the smell of the woodpile on a cold December evening is among them. Also at one point one of Abel and Junon’s grandkids appears on screen dressed as a knight for the little impromptu Christmas play they’re staging, which reminds me of a brief and mortifying appearance I made in my church’s Christmas pageant as a child: I was dressed as a knight, and the passing Good King Wenceslas (a church teenager) caught his robe on my cardboard “armor”. As an adult I know the audience’s laughter wasn’t AT me at all, but as a kid of course it felt like I was the butt of the joke.

I Understood That Reference: We do catch glimpses of the creche at Abel and Junon’s home, where the grandkids wonder when Jesus will show up. Slightly later on, Faunia and Henri have a couple of brief exchanges that allude to Christian practice/Jesus as a central figure for the holiday, in connection with Faunia’s identity as a Jewish woman who wants to duck out before Christmas itself is fully under way.

Holiday Vibes (7.5/10): There’s no question that we are fully immersed in a household at Christmas, where things like a big family dinner and a Christmas play occur, not to mention the trip to midnight mass, etc. But big chunks of the movie take place outside that immediate context, and also Christmas itself is usually sidelined by whatever emotional trauma a character was working through on screen. Overall, this is a fairly Christmassy movie but not achieving peak levels of holiday.

Actual Quality (7.5/10): It’s very hard to give a fair rating here. Critics would place this as a 9 or a 9.5, as far as I can tell. In terms of my moment-to-moment comfort with the film, it played a lot like a 5 or a 5.5, much of the time. It ages a little better in the days after seeing it than I had expected it to, though, so that I don’t think a 5 would be a remotely fair rating, and I can certainly see the good craftsmanship in it. I’m splitting the difference then, but I want to acknowledge to you that I think the movie’s pretty polarizing, and that you’ll probably have one experience or the other, rather than a “7.5, fine but nothing special”.

Party Mood-Setter? I mean, I kind of still have no real idea what I watched, so I am reluctant to rule it out, but I don’t think it would work. It’s just too dense with characters and exchanges and subtext for you to not pay attention to it. Also, unless you are a speaker of the French language, you’ll have to be reading the subtitles to follow it, which isn’t great for a background movie.

Plucked Heart Strings? You know, it really seems like I should have been emotionally invested, but all these characters are so inscrutable that I couldn’t say I really connected with it at any point in this way. The meanest things they say to each other would hurt feelings in real life, but if they’re hurting feelings, it’s not usually obvious from the way anyone reacts.

Recommended Frequency: Either I need to not bother watching it again or I need to see it six times so that I can actually follow all the nuances of the dialogue and the intersecting storylines enough to really appreciate it. I have no idea which of those two things I’m going to do, genuinely. I think if a complex art house French family drama sounds like your idea of a good time, you should try it, and if it doesn’t, this really isn’t the movie that’s going to convince you to love foreign cinema.

You ought to have easy access to watch the film, if you did want to try it out. It’s streaming (with ads) on Plex, Philo, and Sling TV. You can pay to rent it on Apple TV and it looks to me like some streaming services will let you get it via subscription (maybe a subscription to the IFC streaming channel, or Criterion?). Barnes and Noble will sell it to you on Blu-ray or DVD, if it’s something you love enough to own, and if you’d rather just snag the disc for free at the library, Worldcat suggests you have hundreds of options.