Review Essay

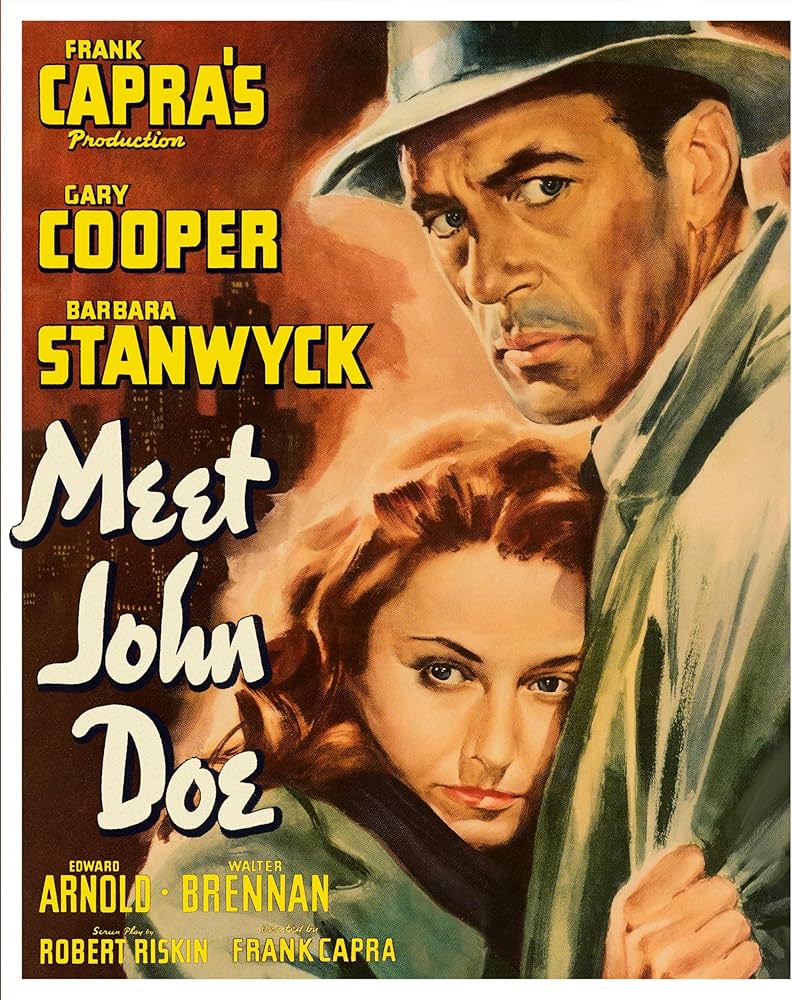

In the long list of 1940s holiday movies—this is the ninth film from that decade to be featured here at FFTH, and I can assure you, I’ve got many, many more on my potential slate for the years ahead—Meet John Doe is almost certainly among the less essential by a few metrics. Its director, its screenwriter, and both its starring performers are all better known for other motion pictures, so that this isn’t anyone’s iconic contribution to the arts. If we think just of the seasonal material, this is one of the ‘40s flicks in my spreadsheet with the fewest minutes of running time occurring on or near any winter holiday. It doesn’t usually get a primetime airing even for more niche audiences—Turner Classic Movies is playing it only once this December, at midnight on December 23rd. Heck, it’s not even the most canonically important Christmas movie of the 1940s to be filed under “Meet,” as those of you who read my Meet Me in St. Louis might have suspected: MMiSL at least offers a classic Christmas song, “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas,” to the cultural stew, whereas I don’t think there’s a single line of dialogue or any on-screen moment in Meet John Doe that would trigger an “oh, is that where that’s from?” in the memory of the overwhelming majority of Americans. And yet? And yet: it’s possible no other holiday movie of the 1940s is more pointedly about America in 2025. If you haven’t yet, this is probably a good year to meet John Doe.

The film’s working with a fairly high-concept 1940s premise: Ann Mitchell is a reporter for The New Bulletin who, on her way out the door after getting canned, decides to embarrass her now ex-boss by writing an incendiary article purportedly based on a letter from a desperate local man. This letter, signed pseudonymously as “John Doe”, decries the problems in the world and concludes with a threat to commit suicide by leaping off the newspaper’s tower on Christmas Eve (which, at this point, is still an unknown number of weeks or months away). When the article becomes a sensation, earning Ann her job back, there’s one problem: everyone wants to meet John Doe. So Ann and her editor (and, eventually, the newspaper’s publisher, D. B. Norton) decide to hire a man to play the part, a down-on-his-luck former bush league baseball pitcher named John Willoughby. As time goes on and Christmas Eve nears, the scheme comes under increasing pressure, not just because Doe’s threatened suicide will have to be confronted, but because in an effort to keep Doe in the public eye, Ann is forced to write (and Willoughby is forced to perform) increasingly bold political rhetoric that inspires citizens from all over the country to take action. The film’s inevitable crises—what will happen when John and Ann’s lies are exposed; what will happen when either John or Ann figures out that the other one is falling in love with them—are of course the major substance of the third act. So far, so good: not that Christmassy, maybe, but I’m not sure how “2025” it sounds, from this angle.

The film’s politics, though, bring it directly to our doorsteps: this is a film by Frank Capra, yes, that Frank Capra, the director of It’s a Wonderful Life, and a number of other films slightly better remembered than this one. Capra’s passion for civic engagement, for the role of the everyday man in the leadership of the country, and for the dangers posed by rich fat cats to the public order, are all on display here. The film opens with someone literally chiseling the words “free press” off the sign outside the Bulletin Building, since the paper’s been bought and the new media ownership want to cut loose a lot of “dead wood” so that they can print more sensational things, regardless of how true they are. That’s Ann’s great mistake in the film, of course—at first the John Doe letter is her mockery of her new editor’s prioritizing fireworks over facts, but when she realizes it’s her ticket not just to getting her job back but to probably a pretty substantial raise, well…she just can’t resist. Ann’s a real journalist, but in this film, she lets herself become a political operative (but one whose political machinations aren’t really well known to the general public). The last 12 months or so have been bad news for the freedom of the press, bad news for the independence of journalists in recently acquired media properties, and bad news for anybody who thinks political journalists can’t also be political operatives and certainly not secret ones. A film that’s critiquing these things has something to say to me, right now.

And there’s a lot more here that starts to feel eerie: why does Willoughby agree to participate in this lie? Well, he’s unemployed and in need of a job…having lost his last one due to an injury he couldn’t afford healthcare to fix. Part of the bargain he strikes with Ann’s editor, Henry Connell, is that he has to get the arm surgery he needs from one of the finest doctors in the country. The owner of the New Bulletin, too, is a magnate whose force dominates the whole country: D. B. Norton is so rich he can buy anybody, and he seems to have what is effectively his own police force in a trained security team we see in action on a couple of occasions. His clear intention is to become President of the United States, and when he realizes how potent a political force these John Doe editorials can be, he deceitfully takes control of the scheme from behind the scenes, knowing that the entire operation is designed not to help the working man, the “average John Doe”, but rather to further entrench Norton and his cronies into positions of power that they can exploit for their own private gain. I mean…you can’t see me but I’m just gesturing wildly in every direction, here, as if to say, “did someone make Meet John Doe in 2025 and send it backwards via time machine?” Certainly we know something about devastating lack of access to healthcare and billionaire domination of the news media and a rich man thinking he can just buy authenticity from his dupe supporters who won’t realize the ways in which he’s using them for his own personal gain. Capra is making a film about the knife’s edge on which American society sits in 1941, an age of progressive reform, yes, but also the age in which fascism erupted around the globe. He knows that a “John Doe uprising” would be as potentially dangerous as it is potentially rejuvenating to the body politic—that, in the wrong hands, a populist movement that was allegedly an expression of the voice of the people (but actually a ventriloquist’s dummy in the hands of the master corporate puppeteers) could wreak great harm. Uh…2025 says, pointedly, “you think so?”

The challenge of Meet John Doe is its intense earnestness—Gary Cooper is almost too perfectly cast as John Willoughby, since Cooper was one of the straightest arrows on the silver screen in 1940s, and making him a man who’s haunted by the sale of his integrity in exchange for a little security maybe hits the nail too squarely on the head. The always electric Barbara Stanwyck is, on the other hand, not quite settled into the role of Ann Mitchell, I think in part because she’s got to play Ann as the deceiver who lies not just to the country but to John Willoughby while also presenting as the loyal friend and romantic interest whose sincere caring for John will be all that holds him together once the rest of the scheme is falling apart. Sure, a lot of romantic comedies play both sides of a coin like this, but this really isn’t a comedy at all—there are occasionally fun moments, but really this is genuine drama, even melodrama, and once we understand the heightened stakes, in which Ann’s lies aren’t just little personal matters but lies that could bring a nation to ruin, it just becomes harder to know why we (and John) are forgiving her, other than that she’s Barbara Stanwyck and she’s got charisma in spades. The earnestness does also tend to lead us to scenes in which big important things are being said, but the dialogue isn’t as true to life as the best stuff that, again, every single major contributor to this motion picture achieves in some other work.

The treasure that Meet John Doe repays us with, though, is, ironically, its intense earnestness. The message is clear from the opening scene in which we see the frightened faces of aging newspapermen, waiting for a punk kid to emerge from an opaque office and gesture aggressively at the many people being “let go” today. Capra sees a country that is being run on behalf of capital and not community—a society that prizes wealth over welfare—and he’s desperate to shake the viewer awake to the danger of it. Sure, Ann’s a liar, but the opportunity she gains through her lies is the chance to tell the truth: through her pen, “John Doe” can denounce graft and corruption, and call for a spirit of moral renewal across the country. The fundamental message of the John Doe movement, as we see it rising, is a clarion call for continuing the progress begun by Roosevelt’s New Deal: as Doe, Willoughby says things like, “your teammate, my friends, is the guy next door to you. If he’s sick, call on him. If he’s hungry, feed him. If he’s out of a job, find him one.” Or, “tear down the fence between you and your neighbor and you’ll tear down a lot of hates and prejudices.” Or, “the meek can only inherit the earth when the John Does of the world start loving their neighbors.” These aren’t just appealing movie principles. They’re the principles I wish animated populism in America in 2025, when movements claiming to speak for “the common man” are far more likely to espouse principles like distrusting and fearing your neighbors who might be liberals or “illegals” or both, and are far more interested in finding ways to rebuild the fences of hatred and prejudice this country’s spent decades trying to remove (and not doing that thorough a job of it, if I’m honest). As corny as Frank Capra and Gary Cooper can be here, what they’re saying has incredible merit. Democracy cannot long survive in a society where we are committed to hating one another, and to the extent that we have the capacity to make democracy thrive, it’s got to have something to do with building a society where we care about and listen to one another. And, in case you’re wondering about those all-important holidays, yeah, the John Doe speeches bring up “the spirit of Christmas” (which seems to be approaching, though there’s not a lot of sign of it on screen) as an example of the kind of selfless compassion for those around you that the Doe movement is trying to awaken.

I can’t tell you if this movie’s going to touch your heart. It is not going to make any secret of its desire to do so, so if you prefer a motion picture with a little camouflage over its sentiments, this is going to seem much too bold. For me, it was impossible not to be moved by what Capra presents, especially (as I’ve been saying) hearing the echoes of all these messages in the resonant chamber that is an America under siege in the year 2025. As regular citizens come forward to thank John for his work, pushing their elected officials aside as obstacles who are out of step with what the country needs now, I think about the everyday people I’ve seen in the streets of the nation this year, demanding care for those in need, and standing up against abuses. The vision of these John Doe Clubs springing up all over America (and their leaders gathering at a political convention that can, yeah, seem a little Riefenstahl for my tastes) might be ominous, but I also wanted to believe in what the movie was telling me, that the members of such clubs are mostly turning out because they are lonely, and restless, and what they know they need more than anything else is to care about the folks living next door to them. I want to believe that regular Americans have that capacity for selflessness, in an age where it feels as though it has been squeezed out of us by the world, and when the film persuaded me of that, well, I was moved.

I won’t spoil the movie’s final act, but there’s so much in it that is plainspoken about what it takes to change a country, and asking whether or not we have it in us—either our leaders or the country as a whole. This is where the movie runs right at Christmas as a narrative, embracing the idea that the incarnation of God as human was, in a sense, a John Doe maneuver. God was down here, a character reminds us, just another joe on the street looking for a place to lay his head. At Christmas, can we turn away from our despair, in the belief that something better has come along and will keep coming along, if we remain faithful? This is a Frank Capra movie—of course his answer is, “yes.” Maybe no other artist of the 20th Century believed in us more as a people. Capra’s mouthpiece in this movie, by the end, is Ann’s editor, Henry Connell, who after going through his own transformation at one point tells John, “I’m a sucker for this country. I like what we got here! A guy can say what he wants and do what he wants without a bayonet shoved through his belly.” Capra was naive, of course, about his country, in which many “a guy” could not say or do what they wanted, not in 1941, not if their skin was a different color than Frank Capra’s. But I think Capra also wasn’t that naive, and that on some level he must have realized that these soaring odes to the country’s values were something akin to the poetry of Langston Hughes, who in the 1930s had written, “let America be America again—the land that never has been yet—and yet must be—the land where every man is free.” And yet must be. How will we get there, I wonder? Henry Connell tells us, in the movie’s final line, which he shouts defiantly at his former employer: “there you are, Norton! The people! Try and lick that!”

I Know That Face: Gene Lockhart, who here plays the somewhat compromised Mayor Lovett, was seen on this blog earlier this year as Judge Henry Harper in Miracle on 34th Street, and he also plays the role of Bob Cratchit in the 1938 version of A Christmas Carol. Harry Holman plays the other important civic leader we see in this film, Mayor Hawkins—in a long career of mostly uncredited roles, one of his last appearances is as the uncredited Mr. Partridge, who becomes so overwhelmed at the big high school dance that he gives up and jumps into the swimming pool in that famous scene from It’s A Wonderful Life. J. Farrell MacDonald, who in this movie portrays “Sourpuss Sam”, a neighbor whose deafness is taken by other “John Does” for snobbery, is all over holiday motion pictures in uncredited roles: he’s an uncredited sheriff in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, he’s an uncredited policeman again in 1947’s Christmas Eve, and he gets about three lines of dialogue as the man whose “great-grandfather planted that tree” that George Bailey’s car had (or hadn’t) run into in It’s A Wonderful Life. And of course we can’t forget Barbara Stanwyck, here in the slightly underwritten role of Ann Mitchell, who of course is so memorable in films already covered by this blog, whether we’re talking Remember the Night last year or Christmas in Connecticut this year.

That Takes Me Back: It is wild to me, to think that once a letter to the editor might have meant anything to people in power, let alone be so persuasive that it’s plausible on any level that it would yield action on public policy. Oh, for the age of the citizen. I always smile a little at milk delivery (one of my grandfathers was a failed milk truck driver, who learned the hard way what happens when you forget to set the parking brake – well, his story was that the brake had failed and honestly, I wasn’t there and he was so let’s give it to him) and at soda jerks, since the image of a soda fountain is somehow both impossibly remote to me and something that would have been fairly ordinary to my parents in their youth, I think? As a map fan, too, I always like spotting a map on screen that reveals the era: in this case, it’s a map of the United States that includes only 48 states, a then-accurate accounting.

I Understood That Reference: The only hint I caught of it was Ann Mitchell calling Jesus Christ “the original John Doe”, though I think (especially under her desperate circumstances) even the original John Doe would be forgiving of the fact that Ann takes some journalistic license in how she retells the story of Christmas to suit the needs of her audience.

Holiday Vibes (2/10): So, Christmas is super important to the characters rhetorically at a couple of points, and certainly the timing of Doe’s alleged Christmas Eve suicide keeps the holiday a live conversation subject throughout, but it’s kind of shocking how completely absent really any of the trappings of the holiday are here. As a measure of “vibes” I have to just acknowledge that even when it’s definitely Christmas Eve and the characters are talking about the fact that it’s Christmas, this is a film that doesn’t really lean into that Christmas feeling.

Actual Quality (8.5/10): I can’t pretend that this film is a smooth, successful motion picture in every respect: the dialogue is often clunky or didactic, the narrative is at times pretty hard to treat as plausible, and when I think of the best stuff both Capra and Stanwyck have done on this very blog, I know this isn’t either of their best work. Again, though, I’m reviewing this film at the perfect historical moment to want to lean into it and listen—to think about how much of it is a fantasy as opposed to the kind of renewal that’s really possible. And these are undeniably still talented folks, who, sure, have made even better movies, but those movies were GREAT, and therefore I think it’s no accident that this movie is still pretty good.

Party Mood-Setter? Definitely not: it’s just not holiday enough, though the film’s pleasant as a companion. You have so many better options.

Plucked Heart Strings? There’s something moving about the people’s faith in John, and Ann’s impassioned speech at the end. I’m not sure how misty-eyed it made me, but I don’t think it’s inaccurate to say that I felt a lot of the things it was asking me to feel.

Recommended Frequency: If you’re going to watch this at any point in your life, this is a good time to do it. The country could use a plain-talking John Doe (and a savvy newspaper lady like Ann Mitchell) and I hope we get the real deal someday.

Meet John Doe is in the public domain after a failure to renew copyright, so there’s a lot of free copies floating around (many of them from poorer, older prints of the film, so if you try out a streaming version and the quality’s poor, I’d look for another one). If you don’t mind ads paying for your streaming, you can watch the film for free at Tubi, Pluto, Plex, the Roku Channel, or Fandango at Home. If you’re a subscriber to Amazon Prime, you can watch it ad-free there, and I think subscriptions at some other more niche sites (like MGM+) carry it also, but I wasn’t able to check them all. You can get it on disc, of course, if you like to own your physical media—Barnes and Noble’s got it in Blu-ray or DVD, as is almost always true. Worldcat says there’s a disc for checkout at over 1,100 libraries worldwide, too, so I bet you can watch it for free just by using your local library!

I know tomorrow’s a busy day for many of us, but I hope you’ll have time to swing through for the blog’s final movie of the year: it’s a short film, and I think you’ll find, if you can uncover a free half hour in your Christmas festivities somewhere, the work might add something really pleasant to the experience. I’ll tell you all about it, of course—see you then.