Review Essay

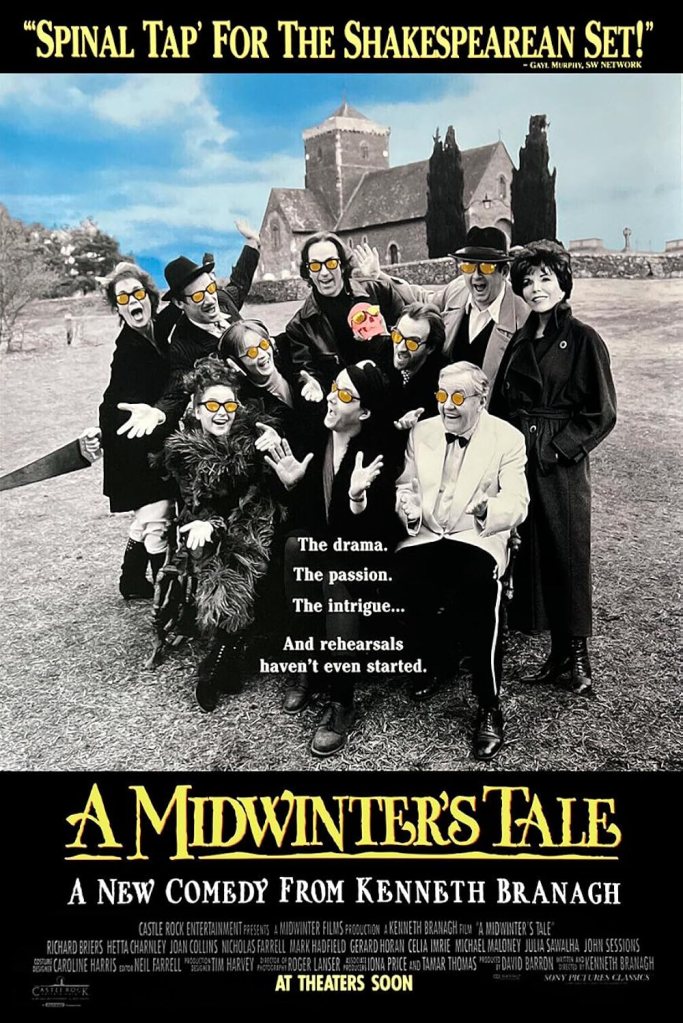

On the face of it, there’s little reason to think of any of William Shakespeare’s plays as holiday fare — sure, Twelfth Night name-drops the celebration of Epiphany in its title, but the holiday makes no appearance in the text. So when I tell you that Kenneth Branagh’s black-and-white arthouse dramedy indie film, A Midwinter’s Tale (titled In the Bleak Midwinter in the UK), nearly persuades me that Hamlet is as much a work of Christmas drama as Die Hard is, I do expect some pushback. But that’s only because you (probably) haven’t seen the movie yet. Because you haven’t yet come face to face with Joe, the play’s forlorn, neurotic, desperate director, as he turns to his rag-tag cast of community theater actors and admits, very much in the style of the Bard’s existentially depressed Danish prince, saying “As the Yuletide season takes us in its grip, I ask myself, what is the point in going on with this miserable, tormented life?” And then, slowly but astonishingly, he gets his answer, much of it mediated through the experience of staging Hamlet itself. I think this is a Christmas story most of us need, and yet one we rarely get.

Don’t get me wrong — so much of this film is a comedy, and a comedy that is pitched directly at anybody who’s ever been a theater kid for even a single high school semester, since so much of what the script finds funny is the embarrassingly human ways everyone from stars to bit players to techies behaves in proximity to even the smallest, most underfunded attempts to put anything on the stage. Weird warmup exercises, arguments over billing, bizarre character choices, chaotic dress rehearsals: it’s all here. The premise is one part Muppet Show and one part A Chorus Line — Joe is an actor/director who’s had his chances and they’ve come to nothing, so he’s hanging all his belief in art and humanity and himself on the possibility of staging an avant-garde production of Hamlet in a crumbling church in the English village he grew up in and ran away from, on Christmas Eve evening no less, in order to raise enough money to keep the building from being knocked down by a developer. He’s going to try to pull it off with a band of ludicrously panicky and self-doubting performers, none of whom he can afford to pay really (despite his implied promises to the contrary), driving them all off into the countryside himself in his dilapidated old car. “With live people in it?” he’s asked incredulously, early on. “With actors in it,” Joe replies, “there IS a difference.”

It’s that kind of self-deprecating, joking tone that pervades this affair. It’s shot with restraint by the normally egotistical Branagh (I mean, love him or hate him, Kenneth’s self-regard has a gravitational field the size of a dwarf planet) who in a rare move doesn’t even cast himself in the film, though the actors on screen are a wonderfully talented collection of folks, more than a couple of whom will be very recognizable to anybody who enjoys British movies and/or television. After a cringe-inducingly funny collection of audition scenes, Joe’s selected his ensemble and the cast relocates to the old church which will serve not only as their theater but also as their living quarters for the last couple of weeks of December. We get to know what it is about each of these people that makes them self-deluded enough to join this absurd enterprise, and what it is about each of them that makes them vulnerable while they’re doing it. And it’s not about Christmas at all, in part because every single one of these people is running from the kind of stability that would give them somewhere better to be on Christmas Eve than working effectively as a volunteer playing five bit parts in Hamlet to an audience that’s likely to be largely (if not entirely) plywood standees. But also it’s exactly about Christmas, because it’s about the connections you find when you’re not looking for them, it’s about the ability to find something larger than yourself to care about when you’re scared of who it is you are or have become, and maybe most of all it’s about the kind of grace that human beings in all their bustling, silly foolishness badly need yet so rarely manage to find. In the meltdown I quoted from in the first paragraph, at another point, Joe shouts at the cast, overwhelmed in the knowledge of his grief that he’s failed them and they’ve failed him and all of them have failed Shakespeare and the village church, “It’s Christmas Eve, for Christ’s sake, you should all be with your families!” Only to have the person he maybe has failed the most say back to him, “We’re WITH our family!” That’s the kind of dramatic gesture only an actor could make, maybe, in such a way that it’s both not true at all and also it’s deeply, deeply true. Made true by saying it, even, perhaps.

The script makes fools of each of them, individually, but it also denies nobody their moment to say something genuine and loving. Even the most seemingly horrible member of the cast — a proud, bitter homophobic old Shakespearean named Henry, played with flair by the immensely talented Richard Briers — has the capacity for warmth. In fact, what we see in him over the course of the play is maybe its greatest argument for our capacity to be redeemed, since Henry’s growth is pretty profound: he goes from sneering contemptuously to rushing with compassion to support someone in pain, and we can see on screen what it is that’s changing him as this unfolds. Now, managing that tone may be where it loses some of you — it’s hard to switch gears between chuckling at someone’s antics and holding your breath as that same person admits some private burden they’ve been carrying this whole time. But to me, again, that’s the Christmas magic of A Midwinter’s Tale, because that very balancing act, it seems to me, looms as a presence in most of the holiday’s best art — Scrooge’s malicious glower transformed into gleeful generosity; George Bailey’s suicidal panic giving way before Clarence’s angelic whimsy; the madcap comic antics side-by-side with the painfully real deprivations of the Herdmans in The Best Christmas Pageant Ever.

Ultimately, A Midwinter’s Tale is an argument about art — as Hamlet relentlessly breaks down each of the performers, one of them observes to Joe that “Shakespeare wasn’t stupid”. That, in fact, he has as much to say about grief, about fear, about family and friendship, about the human condition now as he ever did. Not because of all the humans who ever lived only one kid from Stratford-upon-Avon ever figured us out, I think, though maybe Branagh would make that argument. But to me it’s more that the film argues that, by giving themselves to an enduring work of art, the people involved come away from it greater than they were before. That the sacrifice of making something — even if it’s only for themselves; maybe especially if it’s only for each other — isn’t a subtractive experience but an additive one. Sharing this film with all of you is one part of why I wanted to write a blog called Film for the Holidays, because I think the additive possibilities of art are pretty potent this time of year, and I’m hoping at least a couple of you find this film works for you the way it works for me. And even if it doesn’t, I hope you at least get some laughter out of it, and a smile or two at the (too-neatly-wrapped-up) ending — I watch it every December, and I never grow tired of it, myself.

I Know That Face: This is a stacked cast of British character actors, and therefore this crew has done a lot of fun Yuletide appearances on screen. Michael Maloney (who plays the play’s director as well as its star, Joe) played Bob Cratchit in a 2000 TV movie version of A Christmas Carol. Richard Briers (the aforementioned Henry Wakefield, a self-described “miserable old git”), as his final role, voiced Mouse in Mouse and Mole at Christmas Time, and had previously voiced Rat in Mole’s Christmas, a TV adaptation of The Wind in the Willows. Nicholas Farrell (who plays the many-roled and many-accented Tom) appeared as none other than Ebenezer Scrooge in the 2022 A Christmas Carol: A Ghost Story, as well as being the Duke of Glenmoire in Christmas in the Highlands. And, in a fun cross-over, Mark Hadfield (who plays Vernon, part actor and part ticket seller) is in another Kenneth Branagh film, Belfast, playing George Malpass who, within that film, is playing Ebenezer Scrooge…opposite John Sessions (who in A Midwinter’s Tale plays Terry, the gay actor presenting Queen Gertrude in drag): Sessions in Belfast appears as Joseph Tomelty, who interacts with George Malpass’s Scrooge playing the role of Jacob Marley (in what ended up Sessions’s final screen credit).

That Takes Me Back: It’s fun to have this look back at the very end of the era in which you’d take out a newspaper advertisement for a casting call — I have to assume, at least, that by the turn of the century these things were mostly digital. I just had to call the year 2000 “the turn of the century”, folks: that one stings. Anyway, other nostalgic stuff here: well, as I’ve remarked before, payphones are incredibly nostalgic, and I can’t imagine there are as many great dramatic possibilities these days in films as there were when you could put a group of people in an unfamiliar setting and force them to hike multiple blocks just to use the phone. In one of the movie’s pointed arguments about community versus commerce (which is yet another Christmas-adjacent angle I just didn’t have room for in the review essay), a character comments that kids these days care about Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. And kids did, back then! It’s funny to reflect on the fact that Hamlet’s clinging to the edges of our pop culture more effectively than the Power Rangers do these days — the characters could have used that perspective in the argument in question, I think.

I Understood That Reference: There’s not a ton here that intersects Christmas tales in particular, but at one point Margaretta, the agent who very reluctantly put up just enough money for this production to keep the cast from starving, suggests Joe could contact Santa Claus for some cash when he comes to her appealing for more funding. I chuckled, anyway. Oh, and this doesn’t really count, but this came out the year after The Muppet Christmas Carol: I highly doubt Branagh intended a nod at that film rather than at the Muppet Show “let’s save the place” esprit de corps of the movie he was making, but I’ll admit, when I see two members of the cast huddled in their church lodgings under matching Statler and Waldorf comforters they seem to have pulled out of a rummage sale bin, a) I want those comforters for myself, badly, and b) I do think of Jacob and Robert Marley, this time of year.

Holiday Vibes (3/10): I mean, in literal terms, I should probably set this even lower — despite the Christmas Eve timing of the performance, neither Hamlet nor anything around it is specifically holiday themed. I do just think that, as I argue in the review, this is a film that in fact is very concerned with the things we think about and reflect on in the holiday season. And by now I’ve watched this so many Decembers that it just feels like Christmas to me, so my real number’s at least a couple points higher, and I can easily imagine that for many of you, your real number might end up a point or two lower.

Actual Quality (9/10): I can’t tell you this is a perfect film, even if it’s one of my favorites to watch this time of year. The ending is a little too rushed and has a couple of weird loopholes, and any 1990s comedy is going to have at least a couple of jokes that make you uneasy (though I do think this movie mostly deals pretty critically with the problematic things characters say). So much of it works, though — a brilliantly talented cast getting to play both the comedy of throwing together a production of Hamlet and the painful drama of that play itself and also the feelings it stirs up in those performing and watching. I really think it’s wonderful, and I think you might find you like it, if you give it a chance.

Party Mood-Setter? Haha, do I think you should just throw this monochromatic indie dramedy on in the background while you’re making ornaments? No, I don’t think it would work in that setting for anybody other than me (though I would show up at your house, take one glance at the screen, and announce “now, THIS is a PARTY”).

Plucked Heart Strings? I can only answer this for myself, and for me, yes, it gets to me. It’s much more a comedy than a sentimental film — at least, in terms of run time there’s far more comedic material than there is sentimental/serious, and in my own memory of the film is far more of laughing than misting up. But there are a couple of scenes that are so poignant — I don’t see how they could go by without affecting you a little, and they sure do affect me.

Recommended Frequency? For me, again, this movie is in the rotation every single year, without fail. Would it carry that same holiday weight for you? I hope so, but I can easily imagine this is more of a curio for a lot of folks — a once every few years movie, maybe even a “just once is enough” movie. If I get a vote, though, I’m sticking that movie into your catalog of holiday films and encouraging you to watch it when I come over.

If somehow I’ve persuaded you to give this one a go, sadly, here’s where I tell you there’s no free streaming version available to you: you can rent it on Amazon Prime or Apple TV, though, if you’d like to stream it. You can own it on DVD, like I do, or on Blu-ray, like I now want to do after discovering they made a Blu-ray version sixty seconds ago when I Googled this, by purchasing it on Amazon or elsewhere. And it’s more widely available than you might think via the library: Worldcat, at least, reports over 200 libraries have it on disc, if you’d like to try it out for free.