Review Essay

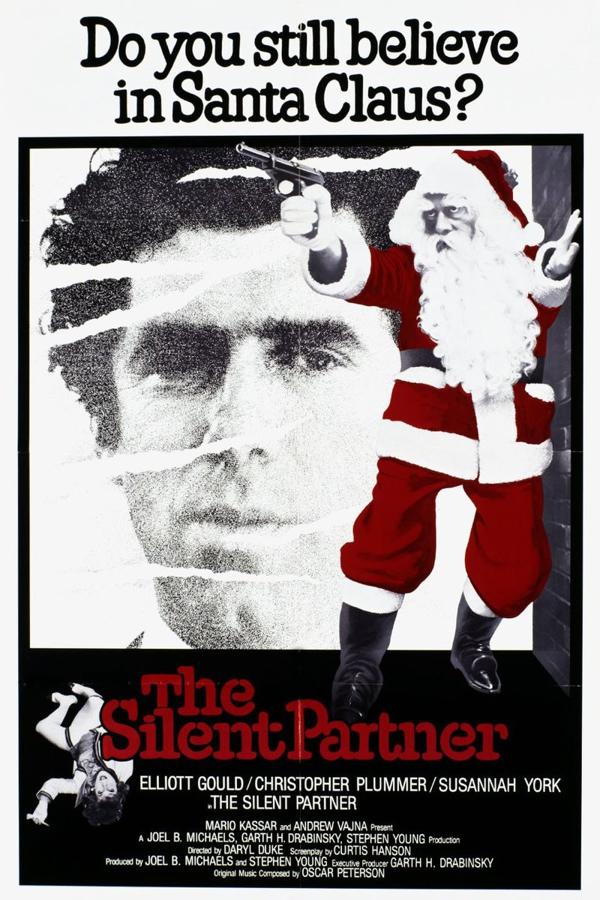

Last year, I commented in my review of the Albert Finney musical Scrooge that I’d selected it in part because the 1970s have a dearth of holiday feature films, and that if I wanted to cover at least one movie from each decade from the 1930s to the 2020s, one of my few other options was “a Santa Claus bank heist filmed in Canada.” Well, it’s a new year and I need a new 1970s representative lined up, so here we go, folks. A couple of readers last year encouraged me to give this one a try, and I appreciate them steering me to something very different artistically, since I’m enjoying exploring the scope of what a “holiday movie” might be. But be forewarned—this film’s very graphic, both sexually and violently, and it’s the violence (and often the sexual violence) of this film that ultimately made it too tough a viewing experience for me to enjoy it much.

There’s plenty of reason why The Silent Partner seems at the outset like a potential hidden gem—in addition to just the amusing nature of the premise of a Santa Claus bank robbery, I notice right away that our main character, the timid bank teller Miles Cullen, is played by Elliott Gould back in his undeniable leading man era, and one of his colleagues is played by a young, fresh-faced John Candy. So far so good, right? Add to that the fact that, as I eventually realize, the crooked Santa is being portrayed by the famously talented Christopher Plummer (in an admitted lull in his long and illustrious career) and it just seems like this film should pop off the screen. The film’s great at evoking the 1970s by just capturing the era as it was—big hair and earth tones, the smoky haze of the air anywhere indoors adding a slightly dreamlike quality—and as a guy who grew up just a few years later, a lot of the imagery made me nostalgic for the media of my youth, at least initially. I was hopeful.

The plot is engaging also, in the first act, when the dominos are aligning. Through a slightly implausible set of occurrences, Miles Cullen realizes that there’s a Santa Claus who intends to rob his mall bank branch, and who specifically plans to come in right after a major retailer has dropped a huge wad of Christmas cash off as a deposit. Planning in advance, he arranges to hide the cash in his lunchbox, so that the Santa robber will walk off with a MUCH smaller heist, while taking the heat for the thousands in missing cash that Cullen will pocket. The robber can’t complain to anybody, of course, given his criminal liability, and thus Cullen will slip away laughing with the perfect crime. The only thing Cullen hasn’t thought about is that the crook under that Santa costume, a hardened tough named Reikle, is absolutely ruthless enough to hunt him down and cause no end of pain and suffering in pursuit of getting the cash he knows Cullen screwed him out of. At that point, it’s a cat and mouse game: Reikle can’t kill Cullen until he knows where the cash is, and Cullen can’t escape Reikle because he isn’t really capable of the kind of violence it takes to permanently rid yourself of a guy like that once you’ve stolen “his” money.

To some extent, your ability to have a good time watching this movie will depend on your patience with a cast of characters who are, almost without exception, neither charming nor interesting. Cullen’s sad sack bank teller desperately wants a woman, and he’s surrounded by people having a ton of semi-fulfilling sex, including a lucky-in-love John Candy—moreover, the environment at the bank is so sexually charged that one of his fellow tellers is a young woman walking around in a tight shirt that says “bankers do it with interest”, a walking HR problem if HR had meaningfully existed in 1978. Anyway, I’d love to tell you that rooting for Cullen feels like I’m pulling for the underdog, but somehow Gould’s portrayal of Cullen never felt appealing to me: he’s sleazy, he’s selfish, he hides a fair amount of misogyny under his “nice guy” exterior, and ultimately he risks way too much danger (and not just for himself) in pursuit of an amount of cash he himself admits isn’t really life-changing. I want him to “win” because Reikle is a monster, and because I know the screenplay has Cullen set up as the hero, but knowing that the movie wants me to think of Cullen as the hero ends up becoming an unsettling experience, since for me, men like Cullen are guys I don’t identify with and don’t want to. And I don’t think the movie is at all self-aware in wanting to explore Cullen’s flaws, though others might see it differently. The same goes for basically every character in the film, other than Reikle, a character the movie’s working overtime to present to us as evil incarnate since that justifies everybody else’s actions (to some extent).

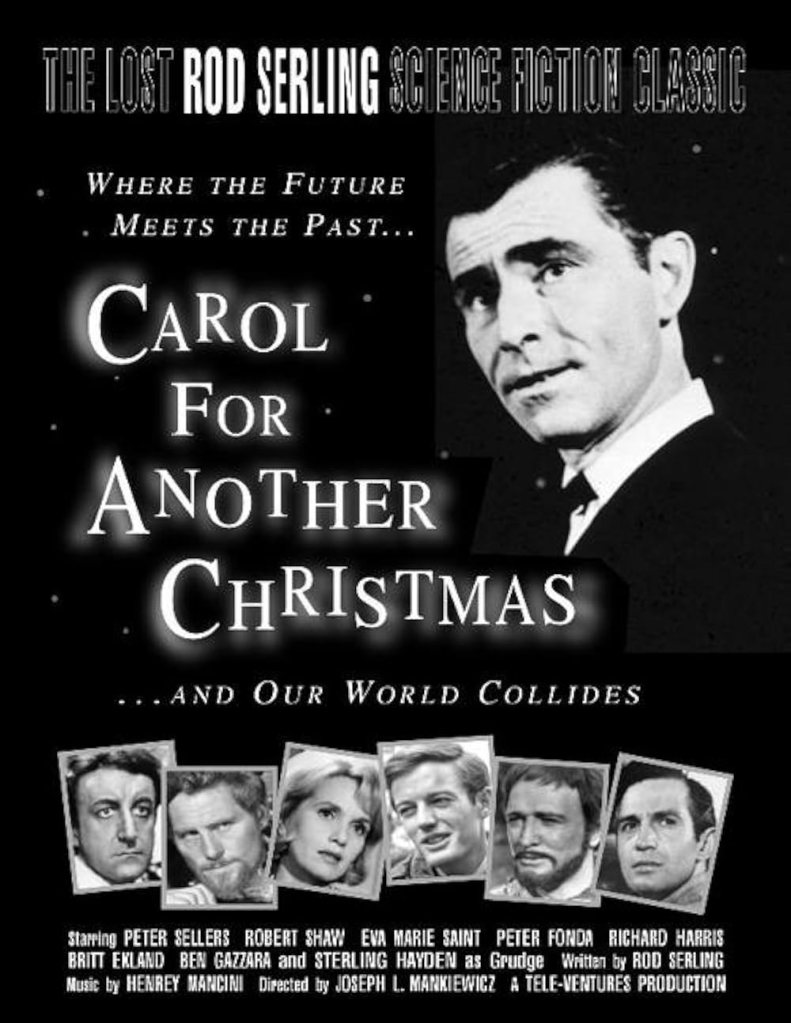

It’s Reikle and the world around him that moves this film from an unsettling watch for me into a really upsetting one. We see multiple acts of violence committed by Reikle against partly or fully nude women, at least one of whom is a sex worker, as he expresses his frustration and his dominance by hurting them. And “hurting” is too gentle a word—I don’t want anybody to be as unaware as I was, going into this movie, that one of the scenes involves the violent decapitation of a woman using the broken glass side of a fish tank. I’m obviously familiar with the fact that horror movies traffic in this kind of outlandish violence all the time, and maybe it doesn’t sound all that intense to you, but speaking as a guy who generally doesn’t watch movies like that, it was an incredibly tough scene to sit through. I think part of the sourness of all this is that I consistently felt the sex and violence were exploitative and not communicative. The woman Reikle murders exists only to be hot enough to have sex with Cullen, and then fragile enough for Reikle to destroy so that he can get back at Cullen, and then important enough to Cullen that he’s motivated by that killing to really ruin Reikle once and for all. But she’s not a person with her own ideas or angle that I can decipher—she’s not a character in this story the way Reikle and Cullen are. I won’t tell anybody they can’t find purpose in the horror of this movie at its most violent, but I couldn’t find it, and I couldn’t really give myself a reason in retrospect why most of the events of the film had happened, other than to engineer either naked women or gruesome violence (or both) onto the screen I was watching. I’ve handled both sexuality and violence really sympathetically here with regard to past films, too, in Carol and Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, so I’m confident it’s not that I’m automatically stuffy or Puritanical about what belongs in a holiday movie. I just want these choices to matter, especially when they’re exposing performers to really vulnerable or even potentially degrading moments on screen, and it’s troubling to me when I think that they’re not being treated with respect.

In the end, I’d say that the film also lets me down by never really knowing what story it’s telling. Cullen at the outset is this nebbishy nobody, someone so harmless that his boss reliably uses him as “cover” by having Cullen bring the boss’s girlfriend to the Christmas party so that the boss’s wife doesn’t figure things out. And yet at some point a switch flips and he’s openly defying a murderous criminal, tailing him home down dark streets and setting up elaborate schemes to entrap him. It’s just not clear why or how he knows how to do any of this, and if he was Kevin McAllister in Home Alone I would shrug and say, this is a child’s fantasy, who cares how Kevin knows to do these things? But this isn’t a child’s fantasy, and it’s too bleak to be a satisfying grownup fantasy (for this adult viewer, anyway…I could believe this is the fantasy of some Reddit incel but the less I think about that, the better). As a result, I don’t know how I’m supposed to understand who Cullen is or what he’s doing, which is a problem in a film that’s 100% about this guy’s triumphs and travails. Reikle, too, is weirdly underwritten: I can’t tell you whether Plummer was playing him as con man or as unhinged megalomaniac or as sadistic freak, and my sense is that the director wasn’t giving him much help to find the character either. I get the feeling that the filmmakers were most motivated by creating something for the male gaze—hot women and gritty violence and in the end the guy that everybody discounted (especially the women!) was the cleverest of them all and gets to both engineer some violence and have a hot woman, maybe even more than one.

I Know That Face: Christopher Plummer (here playing Reikle, our primary villain) narrates a Claymation short film in 1998 called The First Christmas, and in 1990 narrates two other holiday films, namely Madeline’s Christmas and The Little Crooked Christmas Tree. Plummer also appears as Scrooge in 2017’s The Man Who Invented Christmas, which maybe someday I’ll add to my rotation of Christmas Carol adjacent films. Indeed, Dickens makes a lot of intersections with members of this cast: Susannah York, for instance, (here portraying the much put-upon Julie) plays Mrs. Cratchit in the George C. Scott adaptation of A Christmas Carol from 1984. Ken Pogue, whose familiar weathered face appears in this film as Detective Willard, is a veteran of multiple Christmas outings: he’s Hank Fisher in 2009’s A Dog Named Christmas, Dr. Norman Ferguson in 2000’s The Christmas Secret, and back in the day he was Jack Latham in 1979’s An American Christmas Carol, in which Henry Winkler plays the miser Benedict Slade under a massive amount of old-age makeup. Most of all, though, you (like me) will have spotted a very young and unexpectedly trim John Candy who here is in the minor supporting role as the bank clerk Simonsen, but who we will all well remember as Del Griffith, the shower curtain ring salesman from the 1987 Thanksgiving movie, Planes, Trains, and Automobiles, as well as, of course, Gus Polinski, the Polka King of the Midwest, in 1990’s Home Alone.

That Takes Me Back: Everything about the bank situation for Miles Cullen was so reminiscent of days gone by (for me): some of you out there have safety deposit boxes, but I haven’t opened one in decades. I can’t remember the last time I was counting out a cash deposit at the bank….maybe back when I ran the staff soda machine at the high school I taught at? And I also can’t remember the last time I handled carbon paper, despite it being everywhere in my youth. Oh, and while this is less specific, I just have to say, every single coat I saw on the Canadian extras roaming around whatever mall this was filmed at reminded me of the coats I was buying in the late 1980s from the local thrift store: I don’t know why it was the winter coats, in particular, that felt nostalgic to me, but it was. Maybe it’s that I didn’t have much occasion as a 10 year old boy to wear a tight t-shirt that said “bankers do it with interest”.

I Understood That Reference: I’ll give it to The Silent Partner: Santa Claus is all over this movie, both cheerfully and violently. It’s really the one successful holiday element in an otherwise not at all Christmassy movie. I wouldn’t say the film deals much in the details of the various Santa legends, but maybe that’s for the best.

Holiday Vibes (3/10): It’s all about those mall scenes—ringing bells and Santa outfits, decorations up at the bank, etc. But they’re done with pretty early on, and once the initial heist takes place, we’re fast-forwarding well beyond the holiday season and not headed back there. Christmas is a bit player here, and since it occurs at the beginning instead of at the end of the film, I think it loses even a little more weight in terms of impact.

Actual Quality (3.5/10): There’s something interesting about the plot machinations here—Cullen’s creativity in solving his problems is interesting, and while neither Gould nor Plummer is really given a great role to play, they’re both talented enough to elevate at least some of the scenes into something more gripping and memorable. For me, though, that’s about where it stops: in the end I don’t think the plot or the characters make enough sense on their own terms, and I’m sure not excited about the ways this story is being presented. It feels far more hackish and less purposeful than I was hoping for.

Party Mood-Setter? Haha, dear reader, I hope you are not throwing any parties in which a violent decapitation would seem like chill background media. If you’re watching this movie at a gathering, I think it must be because this is a film you want to pay full attention to.

Plucked Heart Strings? I mean, there’s emotion in the horrifying acts of violence against women here, but that’s not really what I’m talking about in this category. Ultimately those women aren’t made real enough by the script to be people I’m moved by. I’m just upset, and that’s not the kind of emotion you’re reaching for from a holiday film, or at least that’s how I feel about it.

Recommended Frequency: I’m really not sure how to recommend this movie, which I doubt I will ever watch again—it will work for audiences that are ready for it, but I’m not entirely sure who that is. I think it might well work better as a horror thriller than it does in any kind of Christmas context, but if you like a Santa slasher movie (and I know many such films exist), this is probably one for you to try. Good luck with it.

If, despite my warnings, you’re up for a viewing experience with this film, it can be rented from most of the big players in streaming land for a few dollars. You can buy it on Blu-ray if you’re really sure this is your thing, though I might suggest a quick try at your local library first (Worldcat says about 300 libraries have it on disc) to see if you’re really sure it’s worth owning. And if you’re in line at the bank in front of a guy in a Santa costume, I say, why not offer to let him go ahead of you?