Review Essay:

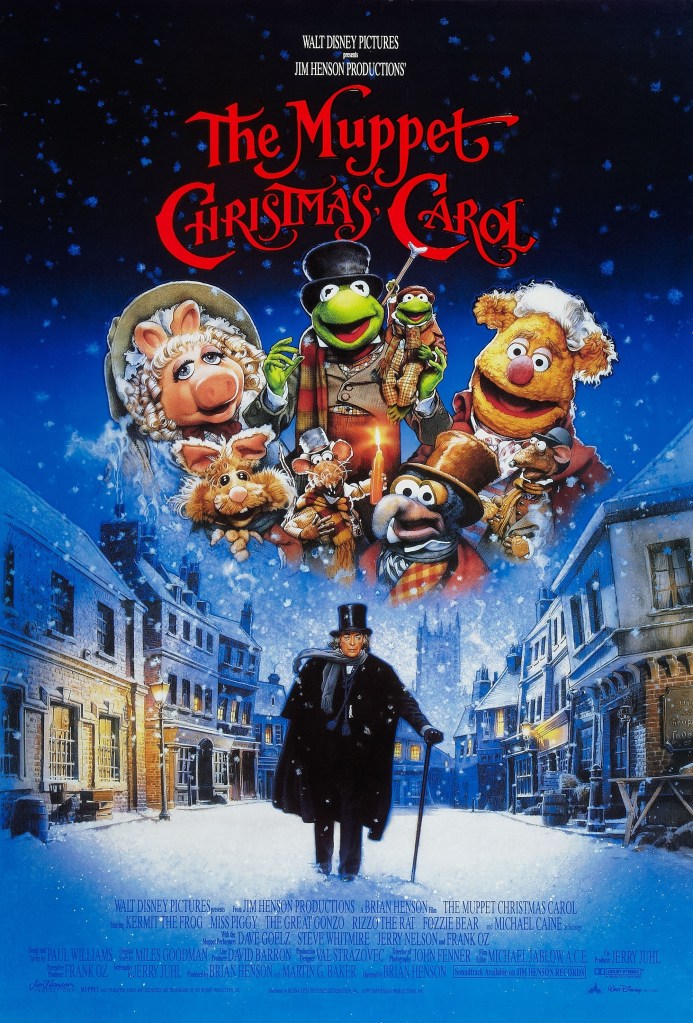

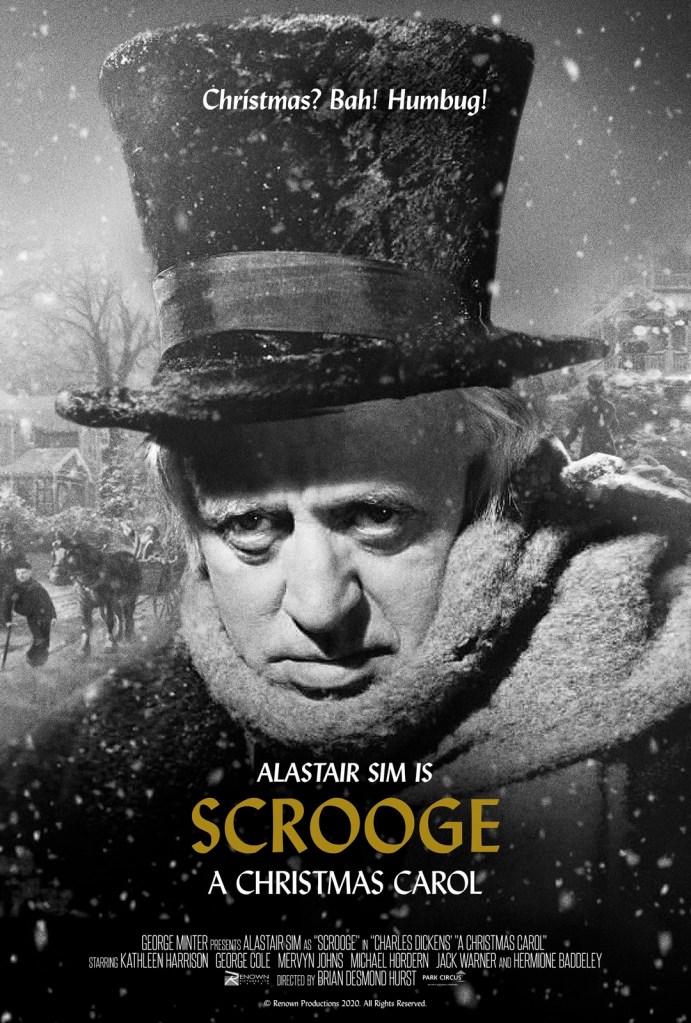

Cheers to you, friends, and thanks for sticking around through most of a blog season, at this point. The end (and Christmas!) is in sight. It’s the last of this year’s Christmas Carol Sundays at FFTH and I knew from months ago where I wanted to finish up this sequence. My first year as a holiday movie blogger, I wanted to finish the quartet of Christmas Carol adaptations with my personal favorite of the many I’ve seen (the Muppets), and this year, I wanted to pay homage to the one I grew up on, my mother’s favorite, the 1951 film, Scrooge, starring Alastair Sim. I hadn’t seen it in many years, but I remembered that in my childhood, whenever it was on television, it was important to my mom to watch it, and my memory was that I’d really liked it. I added it to the schedule and hoped it would meet my high expectations, and the great news is, I feel like it fully did so.

Every really good adaptation of Dickens’s novella has some kind of thematic hook—a way of reading his story that, both in what they include or exclude from the original tale as well as in what they choose to add to the narrative, shows what the filmmakers believe is central to its message. The hook for this film is fear, and I think one of the things that surprised me most (in a great way) is how much the exploration of that fear turns out to be a key that unlocks a lot of really interesting elements in characters and scenes I know so well that sometimes it feels a bit silly to keep coming back to new adaptations thinking I’ll find something here.

For this incredibly faithful rendering of Dickens’s text, the first emergence of fear as a central preoccupation is in Alastair Sim’s magnetic performance as Scrooge. Where other Scrooges on film tend to push other kinds of emotions forward—anger, for instance, or cruelty, or arrogance—Sim’s old moneylender looks haunted from the moment he appears on screen. Some of this is just the hand Sim was dealt by time and fate: his huge, hooded eyes (reminiscent in some ways of Peter Lorre’s) are, by the early 1950s, better at expressing that kind of paralyzed anxiety than they would be most other kinds of emotion. But let’s not sell Sim short: he’s doing a lot of work, too, as a performer to evoke the sense of his fear. We see him darting away from interactions (startled by the man on the steps of the Exchange, for instance, or quietly but firmly insistent that the child carolers move on from the sidewalk outside his office), and indeed, the one flash of his anger early in the story only emerges in response to the touch of his nephew Fred’s cheerful, welcoming hand on his shoulder. Scrooge lashes out in response, pounding the desk and shouting, as though it’s that kind of intimate human contact that frightens and upsets him more than anything else in the world. Other than that, though, the Scrooge we get in these sequences is softer of voice, more restrained than many Scrooges—still a covetous old sinner, to be clear, but it’s apparent that he’s been made the way he is, somehow, by his experience of fear. He seems baffled by Fred’s happy, impoverished marriage more than he is wrathful about it, as though it’s not possible for him to make sense of a life lived outside of the fear of not having his wealth to protect him, and in one sad moment at dinner on Christmas Eve, we see him retract his request for extra bread with his meal once he realizes it will cost a haypenny. It’s a reminder that Scrooge’s severity isn’t just for people under his thumb—he’s just as severe with himself. The miserly impulses of his heart are less a cage he’s trying to trap the poor inside, and more a prison he feels chained within, as well.

Scrooge’s fears are amplified by a number of decisions made by the screenplay that I think add a lot of texture to the story: Ebenezer, in this film, had been the means of his mother’s death as she died in childbirth, and he’d lived a remote and deprived life after his father rejected him. When his older sister (in this version), Fan, comes to get him from school, he tells her how overjoyed he is to be with her again, and she promises him that he will never be lonely again, “as long as I shall live.” But of course Fan does not live; she dies bearing Fred as Scrooge’s mother died bearing him. He opened up his heart once before and lost the one safe harbor in his whole world—no wonder he shrinks from humanity, and from Fred’s kind hand in particular. Furthermore, we learn over the course of the Christmas Past sequence that Scrooge’s whole life is a kind of haunting: his pinched, chilly office was once the warm, friendly office belonging to Mr. Fezziwig, an office that young Scrooge and his partner Marley basically forced Fezziwig out of, years ago. Scrooge’s life, too, is lived in a shadow—he inherited Marley’s house and furniture upon Jacob’s death, which means that of COURSE Marley’s haunting him here, this is literally the man’s home, and the bed from which Scrooge rises to see the first two spirits is the bed that Marley died in. To me, this enriches the film so much: I understand better both why Scrooge doubts the apparitions he at first encounters, and why he comes to believe in them so fully.

The writing, then, is a real strength: I’ll say that, for me, the acting is a slightly more mixed bag. Sim himself as Scrooge is really wonderful, expressive in almost every scene at a level that engages me. Some of the supporting cast rise to his level, but others feel a little stiff or amateurish, which probably reflects just the relatively limited budget and simple approach of this small British production in the 1950s. Maybe the worst of the offenders, for me, is the Ghost of Christmas Past, about whom my complaint really is that he’s forgettable: there’s just not that much personality here on a level that would make his work with Scrooge more memorable. This fault is amplified slightly by the fact that the movie extends the Christmas Past sequence by quite a bit, adding in scenes to help convey how Scrooge changed over time. But these are minor complaints: truthfully, the movie committing to a deep exploration of Scrooge’s past is really effective, because it helps me understand how a young clerk who loved the joy of his kindly boss did grow into the walking black hole of this aged Scrooge, towards whom money is drawn and out of whom no good human emotion seems likely to emerge. And the other side benefit of this long exploration is that it gives the old Scrooge time to make sense of things—he starts to anticipate what each next scene will reveal, and he pleads not to have to face them. This is true in a lot of adaptations, but I think Sim more than any other Scrooge I’ve seen manages to persuade me that by the time the Past section is done, he’s basically been convinced of what he’s done wrong in life. The key to Sim’s version of the man, then, is that even knowing he’s done wrong, he’s still not ready to change, and that brings us back around to fear: Scrooge pleads with both Christmas Present and Christmas Yet to Come that he is simply too old, too far gone. He begs them to leave him in peace as a lost cause and go find “some younger, more promising creature” to transform. This is a Scrooge whose depression has so chained down his heart that even when he knows he is a bad man, he cannot believe himself capable of good. And so the Present and Yet to Come sequences become less about punishing Scrooge and more about forcing him to understand that he has ample opportunity to have an impact, right now and before he’s in the cold ground. It’s marvelously effective.

As a result we get a different vision of the Present than most adaptations supply: we see far more about the whole Cratchit family (and not just Tiny Tim), who really are poised to be helped by a man who can create wealth and opportunity for a bunch of young people on the verge of adulthood. Our glimpse of Fred’s party skips the guessing game entirely (no need to skewer Scrooge further) in exchange for a longer conversation between the partygoers in which Fred can defend his belief that Ebenezer has the capacity to change, and show up as a guest someday. Again, that party’s full of exactly the kind of young people Scrooge was once, people who, as I think he must understand, are about to make the same choices he once made, and maybe could live differently than he has. And most poignantly (here departing again from Dickens), Scrooge’s once-betrothed, here named Alice instead of Belle, is a woman working at one of those poorhouses Ebenezer’s such a big fan of—an angel of mercy to those in desperate need. I said critically of Scrooged that I thought giving him a love interest to reconnect with was too cheap, because it reduces Scrooge’s reforming to being transactional, something he’s doing to “get the girl”. So what I love here is that Alice is never mentioned again—we understand, as Ebenezer surely does, that she’s out there. That a more compassionate, more loving man might even find a bridge of connection to her, in the future. But there’s no guarantee of this, and I think it’s quite possible he never even sought her out: that he understood that the Spirits’ message was not “hey….guess who’s still single?” but rather “you jerk, the only good thing about the poorhouse is the kindness of people too good to stand in a room with you: it’s time to grow up.”

And then Scrooge’s Christmas Day here is such a moving and happy celebration: Sim, who has played the man’s fear so successfully, can unleash the relief of this unlikely chance to live a better life with incredible joy. I like the elevation of his servant, the “charlady” as she calls herself, in prominence as a character here, so that he can have an extended dialogue about how he’s feeling and what he’s thinking about, and apply his generosity directly to the woman he’s frightening. And because this is a story of how a fearful man found the courage to trust other people instead of hiding from them, Scrooge’s arrival at Fred’s house has never hit me with more emotion. Everything about it, from how gingerly he steps across the threshold to the gentle encouragement he gets from the maid at the door to Fred’s wife getting up to extend her arms to him in welcome, and lead him in a merry little dance, is so fully expressive of the gladness of complete redemption. Scrooge can change because loving community is possible, and because (to follow the logic of Dickens’s original tale) in Christmas we are given a holiday that asks us to create that kind of welcome for others. Even if in some ways it feels a little too easy for the old moneylender, in other ways that’s just the dream the story asks us to believe in. As Scrooge himself comments in nearly the film’s final scene, “I don’t deserve to be happy. But I can’t help it!” What better description of grace could there be?

I Know That Face: Kathleen Harrison, who here appears as Scrooge’s charlady servant, is in IMDB’s credits for the 1974 TV movie Charles Dickens’ World of Christmas, but I have no idea what role she played. Michael Hordern, who portrays Jacob Marley (both living and dead), is the voice of the narrator for the British TV series Paddington Bear, which includes the 1976 episode, “Paddington and the Christmas Shopping”. Hordern also voices Badger in the 1980s stop-motion animated series The Wind in the Willows which aired several lovely Christmas-themed episodes, and the man wasn’t done with Dickens by a long shot, it seems, since he voices Jacob Marley again in the award-winning animated 1971 film A Christmas Carol (which I will definitely get to on the blog someday), and he appears in live action as Ebenezer Scrooge in a 1977 TV movie A Christmas Carol, one of dozens of such productions that I’ve simply never heard of. Hordern’s joined in 1971 by Alastair Sim, in fact, who voices Scrooge in that film, reprising his role in this one. And I learned to my surprise, in digging into this cast, that there’s a crossover I hadn’t spotted with another earlier film this year: Roddy Hughes, who here plays good-natured old Fezziwig, has I think a single line as a chemist dispensing medicine in The Crowded Day.

Spirit of Christmas Carol Present: This is a fairly comprehensive version of the original tale, including a lot of things I love to see. A couple in particular caught my ear and eye: not many productions leave in the comment by Marley that he’s procured this chance for Scrooge, with Ebenezer replying, “Thank ‘ee, Jacob.” It’s a sweet note of grace early on. This is one of the very few adaptations that manage to leave in Scrooge being taken by Christmas Present to a coal mine where the workers are singing carols together (alas, we don’t also get their visit to a lighthouse, as in the original). And Christmas Present here gives us a brief glimpse of those starving, near-feral children, Ignorance and Want—less unsettling than the Disney version I watched earlier this year, and I think therefore more affecting?

Spirit of Christmas Carol Absent: As I mentioned, we don’t get the guessing game at Fred’s where the company’s meaner to Scrooge than they are earlier in the evening: it’s an unusual cut, but like I noted, I think I get why emotionally the filmmakers wanted something else. We also don’t get the young couple rejoicing because Scrooge’s death may give them a chance of keeping their home, exchanging that time instead for a very long dialogue scene with “Old Joe” the ragpicker, who’s buying up whatever the dead have left behind.

Christmas Carol Vibes (10/10): The evocation of the original tale, and this time and place, is so effective. There are adjustments, as any adaptation would have to make, but here they’re so in line with the tone of the novella that I had to double check a couple of these innovations to make sure they weren’t in there and I’d forgotten them. If you want the feeling of reading the book, this will suit you to a T.

Actual Quality (9.5/10): Thanks to a well-paced screenplay and a really effective performer in the role of Scrooge, this is a nearly perfect film to immerse ourselves in. Sure, I complained about a couple of semi-flat performances, but really, you hardly notice: the rest of the film keeps chugging along with great skill. I can’t believe it’s taken me this long to revisit it, since it deserves more attention than I’ve given it.

Scrooge? Sim is tremendously successful at imbuing him with humanity: making Scrooge a fearful person instead of a furious one unlocks a way of understanding him as a victim as well as a villain. He’s younger than he looks, too—a mere 51 when this was released—and as a result he has the physical energy to be able to really leap about giddily on Christmas morning, enough that we can believe his housekeeper was rattled. Definitely a top tier performance, and one that is the secret to the movie’s success.

Supporting Cast? This is a slightly more mixed bag—Mervyn Johns is genial but less memorable as Bob Cratchit, and I’d say both the Spirits with speaking lines are just a little underwhelming. Glyn Dearman does a good job with a Tiny Tim who’s right on the edge of being too perfect for even this heightened fable, though, and Rona Anderson probably gives the best performance I’ve ever seen of Scrooge’s betrothed (with apologies to Meredith Braun, who does such a lovely job as Belle in the Muppet version, but Rona’s been handed more dialogue and more screen time, and that makes a difference). Also, as I note, we get a lot more “Christmas Past” time here, which means that we see a lot of Marley and Fezziwig we wouldn’t normally (as well as the actor playing a young Ebenezer), and all of that goes really well. I’d say that this isn’t really the movie’s strength but there’s plenty to enjoy in it.

Recommended Frequency? I haven’t been watching this version every year, given how well I knew it from my childhood, but this viewing made me feel like it really ought to make it into my annual rotation. Sim is so good at the role, and the emotion of the story hit home for me as a result.

You can watch this film pretty easily, if you like: Tubi has a copy, as does Plex, if you don’t mind the ads. If you’d rather pay for an ad-free experience, you can rent it from Amazon Prime. I own a digital copy from Amazon (which I assume is the same version they stream) and I’ll mention that the audio levels are slightly off in some sections: if you notice that kind of thing more than others, I figure it’s best to be forewarned. The film is available under its alternate title of A Christmas Carol (I wonder where they got that?) on disc at Barnes and Noble, and though it’s not as universally accessible as some films, it’s in several hundred libraries, according to Worldcat, and therefore I hope you can borrow a copy for free that way, if you so desire.