Review Essay

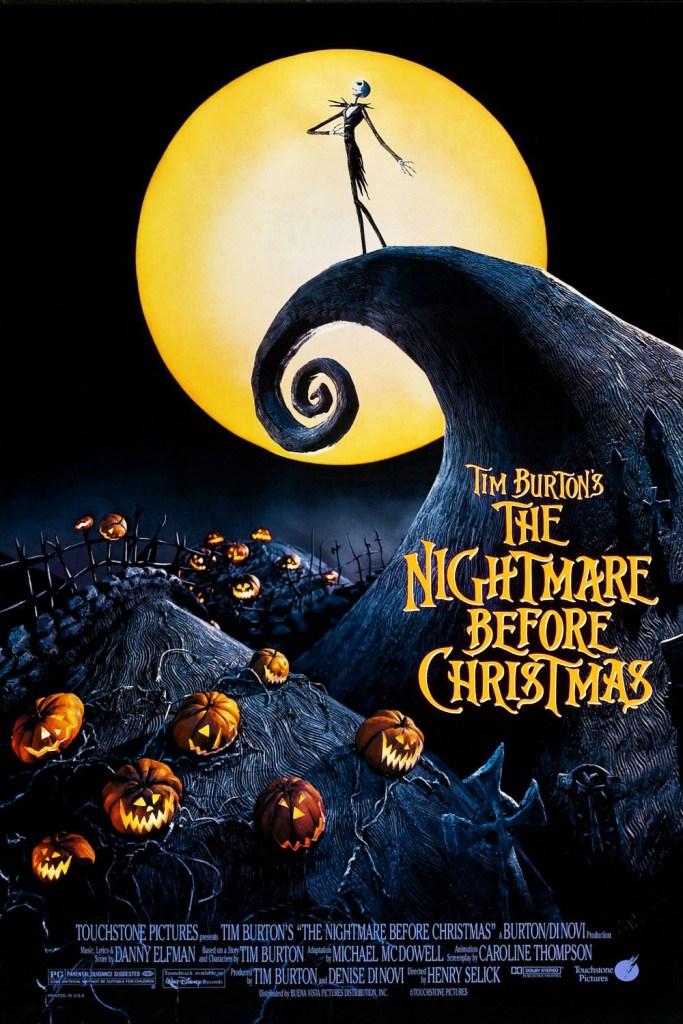

It’s kind of funny that The Nightmare Before Christmas lingers in the public consciousness far more as a Halloween movie than a Christmas movie, despite the fact that (with the exception of the opening scene) the film is really entirely about the late December and not the late October holiday. In a way, we make the same error in understanding that the denizens of Halloween Town do when Jack persuades them to celebrate Christmas—thinking that this experience should be primarily about the expansion of the empire of Halloween’s cultural material into Christmas rather than respecting Christmas as having a value of its own as an entirely different kind of celebration. If we look at the film itself more closely, to the extent that it’s about either holiday (and I’m about to admit some doubts on that front), it’s much more a film about Christmas and what it means, even if sometimes it’s speaking by means of its silence. The movie is a fitting subject, therefore, for the work done here at Film for the Holidays.

The initial premise of the movie is simple enough: the cultural (if not political) leader of Halloween Town, Jack Skellington, the Pumpkin King, concludes the celebration of Halloween one October 31st with a sense of depression and malaise. He’s tired of “the same old thing” and wants to rejuvenate his sense of identity by finding whatever it is he’s missing right now in merely putting on a more-or-less perfect Halloween celebration once a year. His sense of longing is echoed by another resident of Halloween Town, Sally, a stitched-together undead young woman who was created to serve the needs (never fully explicated) of the local mad scientist, Dr. Finkelstein. Sally wants independence from that life and some kind of connection with Jack, but she is both unsure how to get free and unsure how Jack might respond to an overture. When Jack fortuitously stumbles into Christmas Town via a tree-shaped door in the woods, he comes away certain that the cultural conquest of Christmas by Halloween Town will pose exactly the kind of thrilling challenge that will invigorate him again, whereas Sally’s deeply worried about the whole endeavor, foreseeing disaster if Jack pursues this path.

The film’s successful communication of the creepy delights of Halloween Town (realized, of course, both by Henry Selick’s amazing talents as an animator and by maybe the best score Danny Elfman ever composed, which would be saying something) is, I think, part of how we come to mistake the message of this movie. It would be easy, if you haven’t seen it in years or only know it through cultural osmosis, to think that the thesis of Nightmare is that Christmas would be cooler/edgier/more awesome if it had a lot of ghouls and frights and toys with teeth, etc., and Jack Skellington & Co. basically save Christmas by making it hip again. Those weird juxtapositions of Christmas cozy and Halloween horror are the really memorable moments in this motion picture, unquestionably. But the message is in fact completely the opposite: Jack sucks at doing Christmas. The residents of Halloween Town create a Christmas that is so chaotic and stressful that worldwide panic ensues, capped off by a military assault on Jack and his (undead?) flying “reindeer”. Jack is so cavalier about the wellbeing of his Yuletide counterpart, “Sandy Claws” (as the Halloweenians call him), that he leaves the security of “Sandy” to three known juvenile delinquents whose primary allegiance is to the one genuinely bad person in Halloween Town, a sociopath named Oogie Boogie, who proceeds to subject an innocent and panicked Santa Claus to abuses designed to culminate in his murder. I don’t mean to “spoil” a 30-year-old classic that surely almost all of my readers have seen at some point in their lives, but the final outcome of all this is certainly not a newly Halloweenized Christmas, but to the contrary a sense that the two holidays belong very much in their respective corners. This is a story about the importance of a world with BOTH Halloween and Christmas, and of knowing which side of that line to be on.

And that’s what’s always going to be at issue in a project proceeding from the brilliant though often one-track mind of Tim Burton, who generates this film’s original story and acts as producer. Burton is good at celebrating outsiders (and, despite all his successes and riches, at playing the role of the “outsider” himself) but usually he considers it impossible for them to make peace with the society Burton finds both appalling and weirdly appealing. Edward Scissorhands does not find himself integrated into the world around him, any more than Lydia Deetz finds a way to be happy in the world away from the Maitland house. I get the sense that Burton privately thinks Jack’s Christmas is in fact more fun than the real one, but also genuinely believes that it’s just not plausible that Jack’s version would catch on among the “normies” who want to find something pleasant in their stocking rather than something lethal. We are allowed to visit Burton’s Halloween Town and admire its delights, but only he and his stable of outcasts are going to find it a happy place to settle down.

You may not think this a very fair take about a film you love—though, to be clear, I’ve watched this movie happily dozens of times, and I can sing along with it in numerous places, so it’s not a film I dislike! I just think that, viewed through the lens of the holidays it purports to have something to say about, Nightmare’s message in the end is that Christmas people should do their thing and Halloween people theirs. Jack maybe has a renewed sense of vigor at the end of the story, but it’s only a vigor that he ought to apply to making Halloween better, rather than dabbling in something else. This was a film about people initially feeling hollow, aimless, wistful, and in the end, it’s arguing that they can be shaken back to life through a shared sense of crisis, but that probably they should have left well enough alone to begin with. That’s the only sense I can make of the Sally subplot, in which she has a vision, argues for what ought to happen, and then is vindicated almost completely by what occurs. Sally was right, and Jack should have listened—as another character tells him at the film’s conclusion, in fact. Some kind of freedom is possible (as experienced by most of our characters, by the end), but we also need to know where home is, and not to wander too far from it, whether that home is the picket-fenced suburbs or the iron-fenced cemetery. And what IS the Christmas that Jack doesn’t really understand? It’s snowfall. It’s nice toys. It’s a predictable and cheerful celebration in which nothing strange or unexpected happens. Not exactly the most ringing endorsement of a holiday, especially from a movie that has taken such delight in depicting the truly macabre people who make up the population of Halloween Town.

Luckily, I also don’t think that we’re forced to accept the messages art gives us without any agency of our own. We can argue that the characters (and the screenplay) misread this situation, and that other, better outcomes were possible. Part of the magic of Jack’s big number, “What’s This,” is that there is actually something profoundly wonderful about stepping outside the boundaries of your life and seeing something new. I can’t explain why Burton wanted to make a movie that argues Jack shouldn’t ever step through the door into Christmas Town again, but I can at least make the case, for myself, that I think Jack knew a lot more about Christmas’s power than he seems to implement when it comes down to celebrating the holiday, and I would have been glad to see a movie give him (and Christmas) more credit for already having a lot on the ball. After all, when he pitches Christmas at the town meeting, he seems to come from the point of view that the holiday isn’t much like Halloween at all—he’s constantly deflecting weird inquiries and at one point he basically breaks the fourth wall to tell us in the audience that he anticipated that he would have to ham up the relatively innocent figure of “Sandy Claws” to make Christmas sound intense enough to get people’s attention. Why he forgets all this in practice for the next half hour of the movie is not really something I can explain. Furthermore, I’m not sure it’s true: Christmas is a much spookier holiday than Burton gives it credit for being. Its most famous modern tale is a ghost story. Its original narrative is a story of terror (one of the characters appearing in every nativity set is an angel whose opening line is “Do not be afraid!”) and murder (Herod and the slaughter of the innocents) and squalor (both the stable and the shepherds). It is neither a neat nor a tidy holiday—it’s only the sanitized commercial version of Christmas that seems that way, and it’s a disappointment, I think, that Burton didn’t apply his considerable talents to unearthing something more vital in it than he did.

It is a very mild disappointment, though. The more I break this movie down, yeah, I can sure pick the plot and premise apart, but I don’t particularly enjoy doing that. My critique of its missed opportunities is honest, and I think it’s a valid assessment of the film we’re given. But more than critiquing it, I want to enjoy it, and I do: I find Jack charming and the residents of Halloween Town amusing and I sing along happily with almost every zany musical number. In the end, the experience of the art has to matter as much as the analysis of it, right? Anyway, it’s a movie that gives a lot to a lot of people, and I’m one of them, and if you’ve not seen it before (or not in a while) I hope I’ve steered you to it in a way that will help you both delight in it and engage with it thoughtfully.

I Know That Face: William Hickey voices the decrepit, predatory Dr. Finkelstein here—he’s Clark’s Uncle Lewis in National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, which I covered with criticism in a post on the blog last year, and in a 1987 television movie called A Hobo’s Christmas he plays a character named (well, surely nicknamed) Cincinnati Harold. Ken Page, who in this film provides his memorable bass voice for Oogie Boogie, appears as Dwight in 1990’s The Kid Who Loved Christmas, an emotionally heavy television drama with an all-star cast of Black performers. Paul Reubens, who made such a career out of playing charming oddballs and who voices Lock (one of “Boogie’s Boys”) in this film, shows up again as a voice actor in the direct-to-video Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas, in which Reubens plays Fife, a piccolo who plays turncoat against the villain at a crucial moment. Most famously, of course, Reubens plays his character of Pee-wee Herman in lots of settings, including as the titular star of 1988’s Christmas at Pee-wee’s Playhouse, and, bizarrely, as a performer in the 1985 Bryan Adams music video, “Reggae Christmas”. Yikes. Lastly, Catherine O’Hara voices Sally in this movie; she’s familiar to most of us from lots of other projects, but in the holiday realm in particular, she plays Christine Valco in 2004’s Surviving Christmas, as well as the aging character actress Marilyn Hack in For Your Consideration, a Christopher Guest film that ultimately is at least Thanksgiving-adjacent. Oh, and of course she is Kevin’s frantic but seemingly not-that-attentive mother Kate in both Home Alone (which I will cover someday on this blog) and Home Alone 2: Lost in New York (which features a cameo appearance by one of the worst Americans of all time, so I probably am going to skip it for the rest of my life).

That Takes Me Back: It would be hilarious if I spotted elements from life in the demented chaos of Halloween Town that reminded me of growing up in the suburbs outside of Seattle, but no, I’m afraid the delirious world of Tim Burton / Henry Selick didn’t spark anything nostalgic for me.

I Understood That Reference: Jack skims A Christmas Carol and a book called Rudolph, as he seeks “a logical way to explain this Christmas thing”. He later divides chestnuts by an open fire, in an echo of “A Visit From St. Nicholas.”

Holiday Vibes (4/10): This is a film with a ton of talk about Christmas and preparations for it, as well as some of its actual celebration, and Santa Claus (ahem, sorry, Sandy Claws) is a major supporting character, so it’s not nothing! But as I note above, the movie’s intentions here definitely seem to carry it away from much real engagement with Christmas and towards the emotional journey of the main characters (and their realization, in the end, that Christmas isn’t for them). So, it’s doing some of what we look for, but it’s missing a lot.

Actual Quality (9/10): Again, separate from the message and however we feel about it, this is an incredibly well made film: a great voice cast, great music, great stop-motion animation. Sure, I have some mild irritation at the Burton of it all, but even there, I admire a lot of what Burton’s capable of as a filmmaker. I’ve just come to find his stuff a little empty and self-aggrandizing over the years, and while there’s still some gems in his filmography, there’s fewer “10s” in there than I used to think, at least in my opinion. Even if Burton’s wrong about Christmas, though, he knows how to make a compelling story, and so do all the other artists who worked on this.

Party Mood-Setter? If this feels like the holidays to you, absolutely: the songs invite you to sing along and the story’s lightweight enough that you don’t need to focus at all. But if it’s not “holiday” enough for you, I think it’s a little too weird a presence to be in the background.

Plucked Heart Strings? I’m sure some people feel a deep resonance with Sally (and delight that she gets Jack at the end) but I don’t think anybody here is fully realized enough to make an emotional response happen for me.

Recommended Frequency: Oh, this is annual at some point in my household—whether in October, November, or December—and we all know the words to at least most of the songs. If it isn’t for you yet, it’s worth trying to add it to your holiday rotation, in my opinion. Proceed with a little caution, though, about what the movie’s really trying to persuade you to believe.

If you want to give the movie a whirl, it’s on Disney+, of course, since Disney paid for it in the first place. It can be rented anywhere you think of renting a streaming film, and several versions are available on disc at your Barnes & Noble. But there’s no need to pay for it: hundreds of libraries, according to Worldcat, carry this one on disc.