Review Essay

It’s often the case at Film for the Holidays that I’m criticizing (if not lambasting) some movie that other people really love, sometimes a lot of people. Yesterday’s salvo at Scrooged, for instance, presumably ruffled at least a few feathers: that movie has its fans, and I get that I might have irritated some of them with my reading of it. So sometimes it’s good for me instead, I think, to try to make the case for a movie that most people don’t like very much, since I don’t just want to seem like a guy taking potshots. Certainly that’s the context of today’s post, in which I really had a good experience watching Kasi Lemmons’s adaptation of the Langston Hughes play Black Nativity, a film that seems to have left audiences and critics alike feeling disappointed at its mediocrity. I’ll confess, I’m not sure I get why people disliked it, and I’ll do my best at least to explain what it is that moved me about the film.

This movie adaptation takes the Hughes original—a retelling of the original narrative of Jesus’ birth through the lens of the Black experience in America and richly infused with gospel music—and encases it in a new narrative written for the screenplay, the story of a fatherless boy named Langston, growing up on the streets of Baltimore. When he and his mother, Naima, are about to face eviction from their home, Langston is packed off via Greyhound bus to New York City, where the grandfather he doesn’t know presides over a thriving Black church in the heart of Harlem. Langston doesn’t understand a lot of the context of his life: who was his father, anyway, and where’d he go? Who are his grandparents, and why have they been estranged from his mother for so long? How can he, a boy on the cusp of manhood, stand up for himself and his mother, and provide the home he knows they both need—can he, in fact, do that at all? And, speaking of context, what does it mean to him and to those around him to be Black Americans at this point in history—why is he named Langston, and what does the legacy of the civil rights era mean to people living generations in its wake? It’s a film trying to do and say a lot…and I think it succeeds.

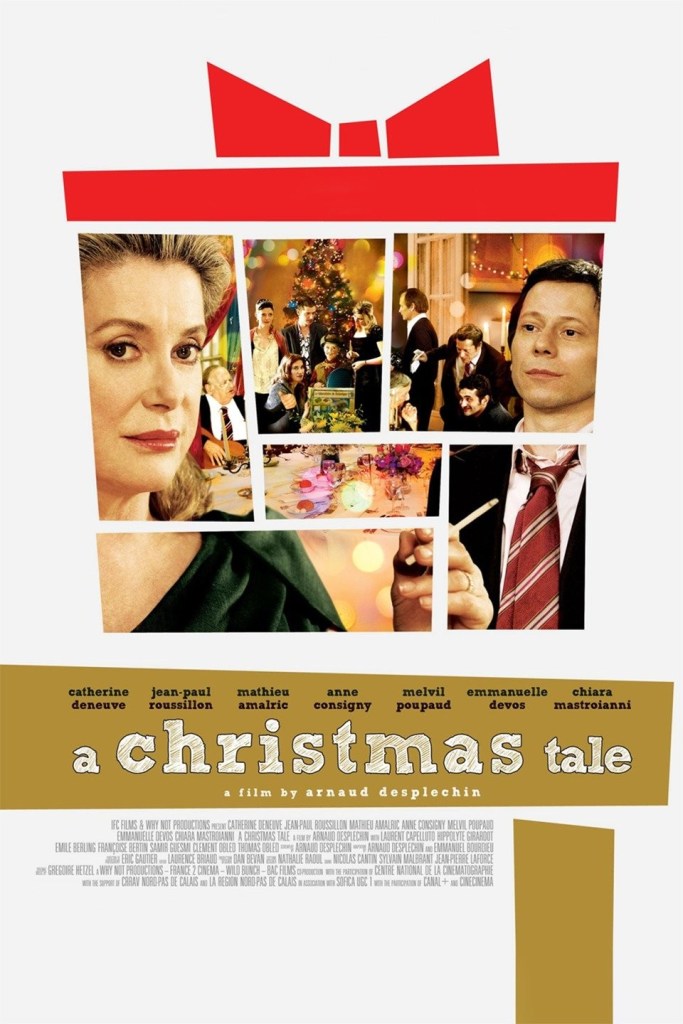

One of the ways it succeeds is by building a lot of thoughtful complexity into the conflicts between characters. As Langston goes unwillingly out of Baltimore via bus, we get to see his mother Naima (played by the multi-talented Jennifer Hudson) singing about the challenges of parenting that she keeps navigating because she believes in him more than she believes in herself, while also seeing his POV, in which he assumes his mother thinks of him as an obstacle and a burden, sent away to relieve herself of a problem. The duality of that parent/child misunderstanding is going to be revisited, of course, when we eventually contend with the much more deeply embedded divides between Naima and her parents (Forest Whitaker and Angela Bassett—friends, if this movie fails its audience, it’s sure not for lack of on-screen talent), and by then we’ve got this lens to help us anticipate that neither side sees the whole story. And even the parents’ side is complicated—a simpler, less thoughtful movie would likely give us a couple upset at their runaway daughter, waiting for her to apologize to them for all the grief they put her through. But here, when Langston starts to get some answers out of his grandparents, his Grandma Aretha says that they’re waiting for Naima to forgive them. And when he painfully confronts them about their absence from his life, almost shouting, “What kind of parents are you?” he hears the pain in their own experience, in the words of the reply: “We’re the broken-hearted kind.” This is a family so haunted by regret and so walled in by grief that they don’t know how to stop hurting each other, yet they also clearly have the capacity to understand that this isn’t a case of the right and the wrong—at least Langston’s grandparents get it on some level from the beginning, and he and his mother are on a journey towards understanding. As Aretha says, herself, at a later moment, “We’re so human. We’ve all done things. That’s between us and God.” Is that an acceptance of blame, though, or an evasion of it? Given her tone and her body language, I see Langston’s grandmother as accepting the reality of what she’s done wrong; her husband’s a more complicated guy, maybe in part because as a minister he’s a little more liable to moralize or try to explicate some ethical truth, but I also see him owning some part of the harm he’s done. When I compare this family and their emotional landscape to the much better reviewed A Christmas Tale, which I wrote about a few days ago, I don’t know—I just find this film a lot more thoughtful, and more willing to believe in our capacity to understand ourselves and each other, which is what I want this time of year, maybe.

Some of the elements in the movie, I’ll acknowledge, are a little too simplified for the sake of the screenplay: Langston’s arrest right after his arrival in New York City feels implausible even for a justice system that’s biased against Black suspects, given what we and the characters in that scene can clearly observe, and the connections he makes with the criminal side of NYC, both in the jail cell and then persisting on the sidewalks of Harlem once he’s free, might be a little too sanitized and convenient. The setup, though, is meant to keep Langston poised between pathways in life. Is he going to be a young man who’s proud of his heritage or one who’s ready to sell his birthright for a bowl of pottage, to use an analogy his grandfather, Reverend Cobbs, would appreciate? Is he going to walk down the sidewalk to the church where he’s the beloved (if wayward) grandson of a family he isn’t sure he belongs in, or to the street corner where, if he plays his cards right, he can pick up the weapon or the illegal goods that maybe can make him the cash he needs to halt eviction proceedings? Everywhere he goes, from a jail cell to a pawn shop to the front pew of Holy Resurrection Baptist Church, he is confronted by not only his legacy, but what his legacy means to generations of older Black men who are putting a burden of expectation on him that he’s not sure he wants (or is able to carry). I’m sure there’s a lot to this context I don’t understand as a guy who hasn’t lived Langston’s life (or Reverend Cobbs’s), but what I could understand of it had a lot of power. I’ll also accept that musicals are hard for a lot of modern audiences, especially musicals set in the real world—it can be a strange juxtaposition between gritty life in the street and a character singing their feelings, and if that’s part of what people reacted to negatively, well, I get it even if I think the musical elements are good more often than they are cheesy.

The movie reaches its high point on Christmas Eve, when Reverend Cobbs insists on Langston accompanying his grandparents to church. From the pulpit at Holy Resurrection, we develop a deeper understanding of what Reverend Cobbs means to his community, as he begins to expound on the story of Jesus’ birth, “according to my brother Luke.” Langston falls into a bit of a reverie here—a dream? A daydream?—and his dream sequence consists of elements of the original Hughes play, staged dramatically all around Langston as though the events of the gospels were happening in the streets of Harlem. The young pregnant woman his grandfather tried to help with a little money is the Virgin Mary; the crook he met in jail has a makeshift tent in an alleyway that Langston pleads for him to share so that the baby can be born. We get an angel and a promise, and as song and dance start to involve all of these characters, even Langston, in the narrative, the events and the words combine to present one of the movie’s basic thematic claims: that Christmas is about a baby who came to put right a world broken by sin, and what “sin” means here is the weight of having done things you regret, things that hurt others and left their mark on you too. From that perspective, we all need the opportunity for a renewal that hardly ever comes back around to lives that missed their chance at it the first time. This is a deeply religious claim about the metaphysics of salvation, of course, but it’s also a simple secular truth that in each new generation—the birth of Maria’s baby, the birth of Langston to Naima—there is a chance of healing where there once was harm. And it’s so overwhelming an experience for Langston that it shakes him right out of his pew. He won’t believe in redemption when he lives in such an unredeemed family; he can’t accept grace in the world if it’s so obvious there isn’t grace for him and his mom. He sprints out the doors of the church into the cold of a Christmas Eve night in New York City, alone.

And even if this movie’s not as good as I think it is, I’m not going to spoil for you what happens then. Black Nativity has a lot to say about it not being too late for any of us, if we’re willing to tell the truth, not just about the hurt done to us but the ways we’ve hurt others. We can be failures by plenty of society’s metrics without being unredeemable—in fact, I’d say this is a film that argues there’s no such thing as “unredeemable.” And an act of unexpected mercy can re-order not just one life, but the lives of many. Sure, there are ways that some of the film’s final confrontations are too clean, too simple. Family is messy, and so is the kind of sin that several characters bring to each other to acknowledge, to accept, to make amends for, and the movie pretends for our sake that it won’t be all that messy in the end if we can be grateful for what we have. I don’t think that’s true enough to the story this film has been telling. I’d say that, far more than “be grateful,” the message we need echoed back to us in the end is that, yes, broken people break those around them. But it is only people who can be authentic in their brokenness who will have the capacity to bring the kind of healing we all need. Regardless, though, the end credits roll on a Black church in the heart of Harlem, a community that knows a thing or two about injustice and hope and dreams deferred, where the choir and congregation are on their feet singing about the troubles of the world and what’s coming to end them all. It’s an exhilarating feeling, for this audience member, anyway. I hope it will be for you, too.

I Know That Face: Forest Whitaker, here playing Reverend Cobbs, Langston’s grandfather, was of course a different kind of distant grandfather as Jeronicus in Jingle Jangle: A Christmas Journey, which I covered last year. Tyrese Gibson, who plays Tyson (or “Loot”) in this film, appears in the role of “Bob” in The Christmas Chronicles: Part Two, the second in a series of Kurt Russell / Goldie Hawn Santa Claus movies that, I suspect, I will have to surrender to and watch at some point.

That Takes Me Back: There’s a pay phone in this motion picture….and it WORKS. I wonder if 2013 is nearly the last year you could put a working pay phone in a movie and not have it feel like a period piece. It sure took me back to having to carry around 35 cents in case I needed to call home. Oh, and one of the ways Langston learns something about his mother is that, when he gets to his grandparents, Naima’s room is full of CDs she left behind her, which express her musical taste (and how young she must have been when she left). I wonder how a modern movie would handle that….stumbling into your mom’s teenage Spotify playlists?

I Understood That Reference: This is the most elaborate / stylized “original Christmas” story I’ve seen in a movie – Joseph and Mary, the innkeeper, the stable, an angel speaking to shepherds in the field, etc., but all of it transformed by this gospel fantasia lens into the story as Langston understands it. That’s certainly the Christmas tale that Black Nativity is in conversation with, as the title makes no disguise of.

Holiday Vibes (7.5/10): We don’t get a ton of “holiday gathering at the family home” stuff, since this family’s in such a weird place, but New York City at Christmas is a pretty powerful energy all of its own, and for anybody who like me grew up with church experiences at Christmas being pretty formative, the experience at Holy Resurrection Baptist Church is very resonant. It’s good at evoking the time of year in lots of ways.

Actual Quality (9/10): Like I said, not a whole lot of people agree with me on this one, but I’m sticking with my own experiences here, and I thought this was a really powerful film. Some wobbles here and there, as noted above, but overall I felt really moved by the characters’ relationships to each other, I enjoyed the gospel music thoroughly, and I think if you’re either someone whose experience of Christmas is similar to the Cobbs family (lots of praying and singing) or if you at least can be culturally curious about the experience of Christmas in the Black American church as an outsider, I think this movie has a lot to say about how those spaces can and ideally should give life to people. 2025 has been a rough year and I’ll take the hope I’m given.

Party Mood-Setter? I’m leaning no, since so much of it is more emotional and intense than I’d normally look for in a background movie, but it’s also true that one of the movie’s big strengths is its gospel soundtrack and you can get plenty of joy out of that just letting it play in the background, I bet.

Plucked Heart Strings? I’ve got to admit: I was genuinely caught off-guard by the movie more than once, with a moment that felt emotionally real in a way I was not expecting. I was tearful by the end, and my guess is that lots of people might feel similarly moved: the emotions being tapped into here felt pretty universal to me, though as I’ve noted, apparently this is not a well-reviewed movie, so there’s something I’m missing (or something others are).

Recommended Frequency: I’d say that this is one I’d love to work into an annual rotation, and certainly one I think you should return to regularly, especially if you’re someone for whom the original story of Christmas “from brother Luke” is a meaningful part of your holiday experience.

Subscribers to Peacock can watch this one ad-free, and if you are happy to watch it with ads, our old standby, Tubi, has got your back again. All the usual places will rent you a streaming copy for about four bucks, and ten dollars will get you a Blu-ray/DVD combo pack at either Amazon or Walmart (Barnes and Noble didn’t have it when I checked). Worldcat says you public library users have options, though: about 700 libraries hold it on disc.