Review Essay:

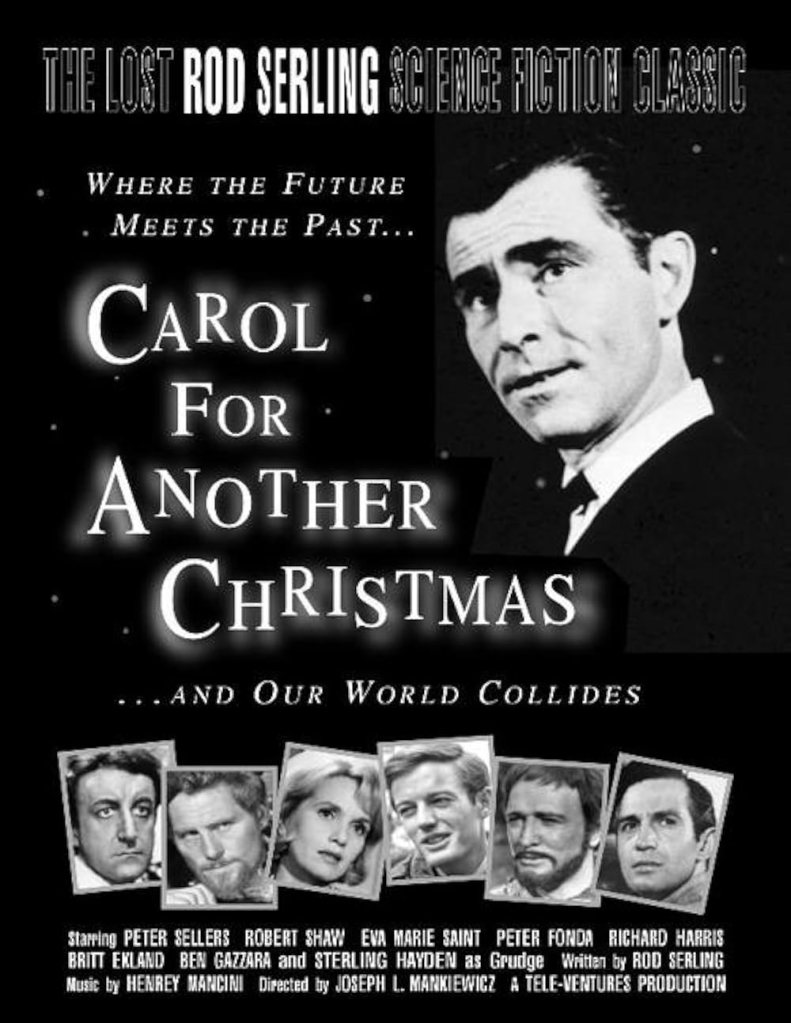

At the outset, I’ll remind you that Sundays at FTTH are Christmas Carol days. Each Sunday, as I did last year, I’ll be bringing you a different adaptation of Dickens’s absolutely timeless classic. Like last year also, I’m aiming for a mix of versions, some of them more traditional and some more experimental: today’s film, a 1964 television movie entitled Carol for Another Christmas, definitely belongs in the latter camp. Anyone familiar with The Twilight Zone will immediately recognize the layered depth of a Rod Serling screenplay, as one of the masters of television suspense and speculative fiction creates something uniquely American out of the classic English story. And you may notice as the film progresses that it feels a lot more cinematic than television movies normally would, especially those of this era: that’s because this is a film directed by four-time Academy Award winner Joseph L. Mankiewicz, director of The Philadelphia Story, of All About Eve, and, maybe most crucially for our purposes, of 1938’s A Christmas Carol, a faithful and widely-beloved adaptation of Dickens’s novella starring Reginald Owen. Mankiewicz, who never directed another TV movie, knows the right ways to evoke the spirit of the tale even as this version of it does away with almost all of the trappings we normally expect from this story, and what remains here is truly powerful, even unsettling, on a level that I think everyone should watch, and maybe especially every American living in 2025 should.

The premise of this film unfolds in the following way: wealthy American industrialist Dan Grudge is essentially alone in his enormous mansion on Christmas Eve, attended only by a couple of servants who know to steer clear of him in his current bleak mood. He is mourning, as he seemingly always does, the loss of his beloved son, Marley Grudge, who died serving in WWII on Christmas Eve, 1944, and whose spirit hovers underneath this film even if he does not make himself visible and audible as an apparition in the way we might expect. A knock at the front door brings a visitor—Dan’s nephew Fred, who mourns his cousin also—and Dan and Fred find themselves immediately at odds as two people who agree on nothing but their fondness for the absent Marley. Fred is a liberal idealist, someone working for international cooperation and peace, which Dan dismisses as dangerous foolishness. Grudge thinks the world can go hang itself, and let America take care of Americans…are you getting restless, yet? Rod Serling’s not going to let you off the hook here, politically—to the contrary, the politics of all this are its point. Dan acts and speaks like someone who thinks America belongs to him and not to Fred; that, moreover, America needs someone like Dan to protect itself from Fred. When Fred tries to soften his uncle by wishing him a “merry Christmas,” Dan’s reply is that he is “in no mood for the brotherhood of man.” Each man is sure that the other one’s ideology will lead to conflict, to global war, to the calamity that threatens the lives of the whole world’s peoples. And while Fred does not issue any ominous prophecies—much like Dickens’s nephew Fred, he merely leaves with words of compassion and hope—something about the exchange ignites the visitations that will haunt Grudge this night (and haunt him they do). Fred leaves and Dan suddenly thinks he can see his son’s reflection in a window. There is a figure who disappears the moment Dan tries to focus on him. The record player in Marley’s room fires up the Andrews Sisters, whose harmonious glee is suddenly eerie, almost unearthly…only, when Grudge runs upstairs to turn it off, he finds that it is all in his head. The player is silent. And then we are in the fog, with him.

The Past / Present / Future structure of the story is retained, but each sequence is radically altered from what we know in Dickens. In the past, Grudge finds himself on a naval transport ship in an endless dark mist-covered ocean, a vessel carrying the bodies of the dead. The vessel’s pilot is the only other seemingly living soul aboard, played by a young Steve Lawrence in maybe the only dramatic role he ever took, but he’s cast well here. His youthful face and voice take Dan back to the end of WWI, a war that he’s still angry about as one that killed a bunch of “suckers” we sent to die for democracy. When the Ghost asks him if Marley was a “sucker”, Dan is startled into understanding the meaning of what he’s been saying. He backs down a little but struggles to explain what he really thinks, and he and the Ghost argue over what really led to a second global conflict, and what he thinks will keep us from a third. The solemn, mournful reality of the dead soldiers around them contextualizes everything they say, and ultimately it’s too much for Dan, who leaves the ship, only to find that the Ghost has brought him to his own past more directly….to Dan Grudge, a commander in the U.S. Navy, with his WAVE driver, a young woman named Lt. Gibson, at Hiroshima in September 1945, one month after the bomb fell. Haunting doesn’t begin to cover how intense and horrifying it is to watch Grudge confront his own memories of the Japanese school girls he encounters there, bandaged and faceless, so wrapped in gauze they resemble mummies, if not the shrouded dead on the transport he just left. He and Gibson, both profoundly shaken by what they are seeing and hearing, argue over the morality of what has happened here, with Grudge defending the necessity, even the morality, of the A-Bomb, and Gibson demanding that he set aside his “simple arithmetic” and deal with the human cost of the conflagration, even quoting the Bible at him in her desperate attempt to waken him into sharing her outrage.

I don’t want to narrate the whole film to you because I want you to watch it – to encounter it with eyes and ears that are ready for (but not guarded against) what Serling and Mankiewicz are trying to say. Dan Grudge, in an attempt to escape the horrors of the past, finds his way to the Present and a new Ghost….but only by walking through the doorway at Hiroshima that led into the room where the Japanese children were being housed. The film rarely misses an opportunity for symbolism of this kind—we can only understand the present by literally walking through the doorway of the horrors committed in the past. The Ghost of Christmas Present takes Dan to the realities of an America in the 1960s that, my friend, I wish I could tell you did not feel like America in 2025. It is a sobering and troubling experience to understand how little our society learned from the 1960s, as Dan encounters the world’s needs and is forced to make sense of how little is being done about them. He and the new Ghost find themselves just as at odds as he was in the Past, with the narrative of a wealthy American man repeatedly wrecking itself on the truth of the reality he has chosen to ignore. It was powerfully convicting stuff, for me. And the Future is maybe the most audacious reimagining possible, as a new Ghost leads him into a post-nuclear-conflict America, where the town meeting hall Grudge knows well is now a shattered ruin, inhabited only by the Cult of the Imperial Me, a sect devoted to the “truth” that there is only one person who matters, and it is Me. The Me at the head of all these disheveled, chattering Mes is played by Peter Sellers at that level of manic, malicious energy that maybe only he could have delivered in 1964—the performance is astonishing, as is the world Serling imagines. Dan Grudge has to reckon with the chaos and violence of a world in which “looking out for yourself” has become the one watchword of humankind—a hellscape so bleak that, when one character unexpectedly advances the argument that we can have law and ethics and honor and decency because “these things were not destroyed by the bomb”, the appeal is not only laughable to the other survivors, they find the suggestion that humanity can be good so insane that it amounts to treason against the “non-government” of the Me People. The violent conclusion of this sequence is not visually graphic (this is a TV movie from 1964, after all), but in emotional terms it could hardly be more unsettling. Grudge is so tormented by what he has seen and heard that he throws himself at the Ghost of Christmas Future’s feet, begging to know what happened to him in this desolate future and whether these events could be altered or whether Fate had already committed the world to this end. And then he is looking up at the curtains, and the picture of his son Marley. The bells are ringing. It is Christmas morning.

In the same way that the film thus far has been a dramatically altered version of the Dickensian events, the conclusion to the film is different also—Grudge is not a gleeful, celebratory presence in this epilogue as much as he is a chastened, bewildered, shaken version of himself, a man still reconstructing his own sense of himself and his world in the unexpectedly gentle morning light. We do not entirely see beneath his surface, but it is clear from what little he says and does that something has happened to him, and that something is happening to him, still. Perhaps the same thing that Serling and Mankiewicz hope is happening to us, the viewers, as we reflect on what we have just experienced. The film offers no easy answers, but the door that Serling holds open to the future is clearly one that assumes Fred has won the argument with Dan about what it will take for the world to live in true and lasting peace.

What, then, is this American Christmas Carol in another guise—who is it for? My feeling is that it’s for all of us. In a way, I think Serling has given us what we no longer really encounter in the Dickens versions of this story—a genuinely convicting and unsettling understanding that WE are being haunted by these ghosts also, that the message of peace and brotherhood is not some easygoing “let’s all hug at Christmas” lark but a truly daunting and monumental undertaking that demands more from us than we might ever otherwise be willing to give. This version of the story, unlike so many others, offers us very little in the way of transformation and hope because Serling does not know from the vantage point of 1964 whether we really will transform ourselves, and therefore cannot offer us too much in the way of encouragement that it will, in fact, all work out for the good. Speaking from the vantage point of 2025, I think perhaps his reluctance was warranted. We learned too little from the 20th Century, and much of what we “learned” as a society was, I think, clearly the wrong lesson, something that has led us into what I will euphemistically call our current predicament. There is an honesty to this version of the story that is not always easy to sit with, but perhaps the time has come again (as it did in 1964) for us to sit with the honesty that art can give us and ask, what next? What now? Will we learn, as Scrooge does in the original novella, to let “the Spirits of Past, Present, and Future strive within me,” so that “the shadows of the things that would have been may be dispelled”? I think we can, and that, muted as it is, this version of the story expresses the kind of hope that we can really believe in—the conviction that all of us, or at least enough of us, may be able to change the course of the future, and bring a better Christmas into being than we would otherwise receive.

I Know That Face:

As I mentioned, the young pop singer Steve Lawrence appears as this film’s version of the Ghost of Christmas Past: later in life, he plays Peter Medoff in The Christmas Pageant. Eva Marie Saint, who in this movie portrays the ethically convicted WAVE, Lt. Gibson, makes appearances as Martha Bundy in 1988’s I’ll Be Home for Christmas (note: ‘90s kids, this is NOT the Jonathan Taylor Thomas flick you’re thinking of) and as Emma Larson in A Christmas to Remember, and IMDB claims that her first ever film role was in 1947’s TV A Christmas Carol, though it gives no indication of her role (I’m assuming one of the Cratchit kids, most likely?). And Pat Hingle, the irritatingly (to Grudge) persistent Ghost of Christmas Present, will later play the Bus Driver in One Christmas, and Joe Hayden in Sunshine Christmas.

Spirit of Christmas Carol Present:

This is maybe a weird claim to make (given that he never addresses the film’s “Scrooge” aloud, as the character obviously does in the original), but Marley’s initial ghostly haunting is really incredibly effective here, more so than in many more straight adaptations. It’s obvious why Grudge would be shaken by the manifestations he hears and sees, and it establishes the basis of the ghost story effectively. To the extent that the original novella is about giving us an emotionally resonant series of confrontations with Scrooge’s underlying moral sense, this movie is knocking it out of the park: at times, honestly, it’s even more affecting than anything Scrooge undergoes, or maybe I should say that I feel the conviction of it more keenly than I do when Scrooge is the one under the microscope. In a way, then, this adaptation is faithful to the underlying reality of the original story, even if it gets there by making some pretty radical alterations to the text. And of course we do get the consistency of our “Scrooge” character waking up on Christmas morning, clutching the curtain that had been Future’s robe.

Spirit of Christmas Carol Absent:

I don’t get into this as much in the review because I’m more excited to talk about what works in this adaptation, but I do have to be honest: there are elements missing from the story that I do think hurt it dramatically to some extent. The moral weight of the dead Marley doesn’t really pay off in the long run here—there’s just not a lot of things for Dan to make amends for in terms of personal harms done, and therefore we don’t really have the sense on Christmas morning that he has a lot of people to settle up accounts with (other than nephew Fred). If Grudge’s servant Charles (who does appear in some of the ghostly portion of the movie) is this version’s Bob Cratchit, that story’s been shaved a little too lean to make it work. We don’t have the same thrill of recognition when Charles shows up, and we don’t see much of a reckoning on Christmas morning, since they just don’t have the same relationship dynamic. And maybe most importantly, one of the most central planks to any Christmas Carol rendering is the idea that Scrooge has some kind of joy in his past (his love of his sister, and his romance with Belle, even just his genuine joy at the overly festive generosity of his old employer Fezziwig) that he can rediscover and re-awaken within himself, which he does on Christmas morning. But if Dan Grudge was ever more idealistic, we don’t see it, and I think therefore we are less sure of his transformation than we might otherwise have been. I think the Past section of this screenplay could have been structured to give us more of an idea that Dan had something to recapture about himself, but either Serling doesn’t really believe that about the American avatar he’s writing, or else he dropped the ball.

—

Christmas Carol Vibes (6/10): This is a fun adaptation in that it does sit between the really faithful examples and the ones that are borrowing nothing more than a couple of names or moments from the classic story. We’ve got a rich old guy haunted by someone named Marley and challenged by an idealistic nephew Fred who encounters three ghosts on Christmas Eve and is affected by them – that’s really effective at making it feel like A Christmas Carol. But the changes to the structure (the loss of the Cratchits in particular as a way of externalizing and dramatizing both the risk and the potential reward of a future that might go one of two ways) and simply the look and feel of the film take it to a very different place. This is much more comprehensible, in a lot of ways, as a long-form Twilight Zone episode than it is as an adaptation of a work by Charles Dickens.

Actual Quality (9/10): In terms of how much this connected with me as an audience member, I’m probably selling it short. This was a profoundly affecting viewing experience, and one that I think worked on me in exactly the ways Serling intended it to, so as an act of persuasion (some might call it propaganda, even), it’s a 10/10. In terms of its quality as a dramatic work, I have to rein it in just a little, since if I stop and think about the loose ends, or the ways the Past/Present/Future sequences do or don’t sync up, I can see ways in which I would improve the film. A fair amount of the dialogue is not especially realistic, as characters argue more as representatives of an ideology or way of thinking than they do as real people with more subtle understanding of the world (though of course the Ghosts are not “real people” per se, so I think that’s less of an issue in this film than it would be elsewhere). But the difference between a 9 and a 10 here is not all that material—whether or not this is flawless film-making (I don’t think it is), it’s a movie that is not throwing away its shot, and that matters. And it’s grown in its power the more I’ve thought about it since watching it, which I think is always the sign of a really good work of art.

Scrooge? As rich American businessman (and former naval officer) Daniel Grudge, Sterling Hayden is playing a role he’s probably born to play, to some extent. I’d say that in this work, he’s effective but often one-note as a stern, jaw-clenching expression of America First thinking circa 1964. His performance is pretty restrained, sometimes so much so that he feels a little limited by the writing, but I think it’s also true that the world around him (both the Ghosts themselves and the theatricality of the visions they present to him) impacts the viewer in a stunning way that’s bound to overshadow almost anyone in the Grudge role.

Supporting Cast? I have to say, I think that all three ghosts are solidly cast and often riveting when they talk. It’s hard to say how much of that charisma is in the writing versus in the acting but it may not matter that much: it’s certainly true that that’s where the power is here, dramatically speaking. Charles and Ruby, Grudge’s servants, are almost wasted in roles that feel like they’re either underwritten or else sequences involving them maybe ended up on the cutting room floor. And nephew Fred is really effective up front as Grudge’s interlocutor and the advocate for a different future, but man, I wish we got more out of him in the finale—either Serling doesn’t know how to use him to draw Grudge out or he just didn’t think that Fred would have done such a thing on Christmas morning, with the bells calling him to his (presumably liberal mainline) church service and testy Uncle Dan seeming unsettled but not anxious for advice.

Recommended Frequency? I think that, if we can stand it, everyone ought to watch this film once, and encounter its artful confrontation of America in the world. It was tough enough to face that one time that I am not sure when I will do it again, but I know that what upsets me as a viewer is not the film, but my own complacency, my fear that in little ways I am a Daniel Grudge who neither thinks enough nor does enough for people suffering in the world, perhaps because I cannot see them from my dinner table in the way that the Ghost of Christmas Present forces Grudge to see them in his vision. I think that until the lessons of this particular carol have been learned, not just by me but by American society, it will always be a text to which we must return, to ask ourselves how much closer we are to peace and understanding than we were in 1964; to challenge ourselves to learn even better than Scrooge did what it means to honor Christmas in our hearts and try to keep it all the year.

If you’re persuaded (as I hope you are) to take the time this year to watch Carol for Another Christmas, I’m afraid that it’s exclusively licensed for streaming to HBO Max, which of course some folks subscribe to via Hulu or Amazon Prime. These days I normally offer DVD/Blu-ray links to Barnes and Noble (given some Amazon business practices many of us, I think very fairly, object to), but only Amazon has a DVD version….and the reviews suggest that the audio and video quality are terrible, so you may not want to drop cash on that. Even more disappointingly, that appears to be the only version available, held on disc (according to Worldcat) by a mere 11 libraries worldwide. I would never normally suggest accessing the film in other ways, since usually we have lots of options for access, but under the circumstances, perhaps you’ll be glad to know that there are some small accounts (surely illegally) uploading copies of this film on YouTube…I assume the copyright holders will take action sooner or later and that link will break, but for now, it’s there. I don’t know where they got their copy, but it doesn’t have the video/audio quality issues folks report about the DVD.

Wow. I cannot believe I have never even heard of this! It definitely sounds like a must-watch, but I’ll be honest, I don’t know if my heart can take it right now. I’ll put it on the list for sure, though.

LikeLike

Yeah, I am shocked the movie doesn’t have a higher profile — The Twilight Zone has such a huge cultural footprint that what’s effectively a Twilight Zone Christmas Carol seems like it should be universally known. Though maybe we’ve pinpointed the reason: like you say, this is a movie you’ve got to be ready to take on (and honestly, I think you’re right to try to choose the right moment). It doesn’t let anybody off the hook, and as time passes, it becomes harder and harder, I think, for us to escape the understanding that we did not learn the lessons of the Spirits, and that we have instead continued to labor in the forging of thicker, heavier chains, of the kind that Marley warns Scrooge about. I’m glad I watched it, but it’ll keep haunting me well into the new year…hopefully in ways that lead me to better action.

LikeLike