Review Essay

Folks, welcome back for another season of holiday movies and musings: it was such fun last year to share some media experiences (both the sublime and the ridiculous…and whatever the heck Ghosts of Girlfriends Past was) with so many of you, and if you’re new to Film for the Holidays, a special welcome to you! As a reminder, these film reviews will be appearing once a day like clockwork from now through the morning of Christmas Eve. You can just remember to pop back here to see them, or click that floating Subscribe button you hopefully see somewhere on your screen to receive the posts via email. All of last year’s categories for notes and ratings are sticking around this season, which I hope will help you both figure out how (or if) to add some films to your holiday experiences and encourage you to explore some titles not even on this year’s list. With all that said, let’s get on with the review of this truly classic motion picture.

My approach to Miracle on 34th Street is definitely influenced by the fact that I know it to be the #1 Christmas movie on the recommendation list constructed by Connie Willis. Willis is one of my favorite authors of all time, on any subject but especially on the subject of Christmas, which she has used extensively as a setting for short stories for decades now, and her passion for this particular movie in the various Christmas anthologies she’s edited is unrivaled. I had the chance to talk with Willis this summer (on many subjects, including the subject of holiday movies), and since then I’ve been asking myself how I would rank Miracle, myself, as someone who absolutely grew up with this film as an annual tradition, but who I think never had quite the same passion for it that its true fans express. The conclusion I’ve come to is that the movie is essentially a perfect object in that it achieves exactly what it sets out to accomplish, and my only issue with it is that the thing I go to holiday media to hear isn’t quite what it sets out to say.

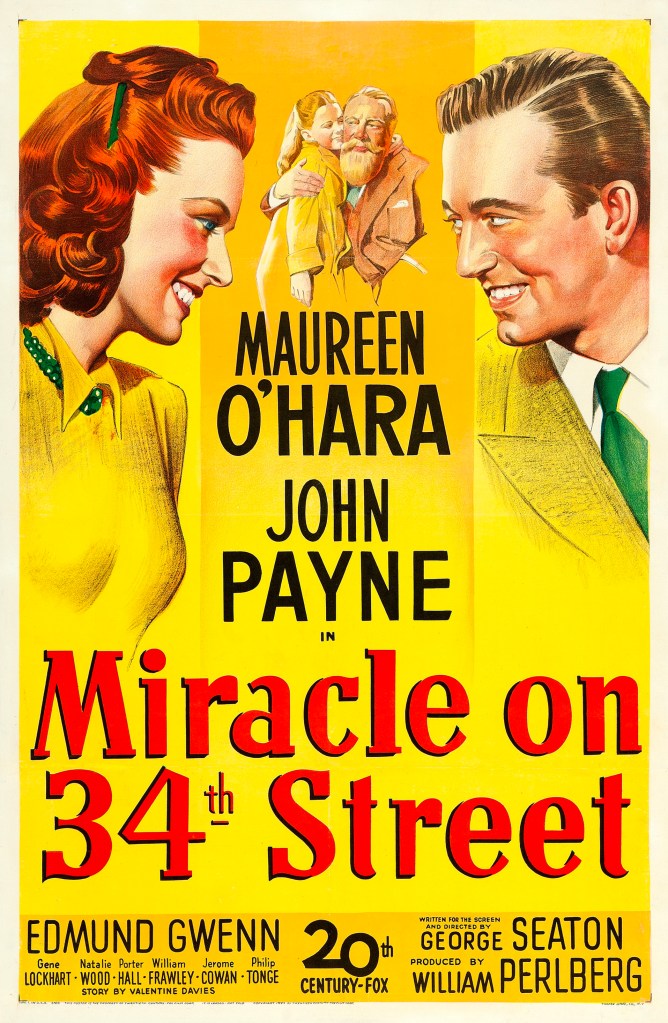

What’s the nature of this perfect object, first of all, if somehow I’m talking to a reader who’s never seen this film? The premise is both simple and silly once you write it all down: Miracle on 34th Street posits that, by the mid-1940s, Kris Kringle (Santa Claus) is living in an old folks’ home in Long Island, taking regular jaunts into New York City to breathe some fresh air, harass shop assistants who are trying to dress their windows for the holiday season, and give pointers to performing Santas as he meets them in the street. Our story begins when, having exposed an unfit Santa on a float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, Kris is hired by Doris Walker, a hard-working single mother and Macy’s employee, to not only take part in the parade but to work the “photos with Santa” line inside their flagship store on West 34th Street in the middle of bustling midtown Manhattan. Kris immediately busies himself with improving the lives of basically everyone he encounters, from Alfred, who sweeps up the locker rooms in the Macy’s employee changing area, to Peter, a kid who wants a fire truck that squirts water but which he will promise only to use in the backyard, to Peter’s mother who, let’s face it, seems like a lady near the end of her rope. Most centrally, Kris’s goal is to convince both Doris, an incredibly hard-boiled divorcee who has seemingly learned to shut out all hope or faith from her live, and Doris’s daughter Susan, a child raised on such pure common sense that the concept of an “imagination” is unfamiliar to her, to believe in him. In this, he has the enthusiastic help of Doris and Susan’s neighbor, a bright young lawyer named Fred Gailey who’s hot for Doris and sweet to Susan, and who is at least willing to play along with Kris’s eccentric notion that he is the real, the one and only, Santa Claus. Wild stuff.

The story as presented feels like it might make a sweet children’s movie—believe in Santa, young folks, and all will be well—but Miracle manages a deeper level of resonance than that, and I think a big portion of the credit clearly goes to the incomparable Edmund Gwenn in the role of Kris Kringle. Gwenn, who wins an Academy Award for the performance, seems to have been born to play Santa Claus, with a warmly smiling and almost cherubic face (if cherubs could grow beards), and perhaps the perfect voice for the part: both cheerful and chiding, he manages to hold a tone that sounds constantly ready to celebrate niceness but also unhesitant to let the naughty know they’ve really stepped in it. It’s that balancing act, a Santa Claus who seems capable not only of genial indulgence but also of genuine moral candor and outright confrontation of the unworthy, that transforms the film into something robust. There’s a wisdom to this Kris Kringle that seems to take at least a note or two from the character’s ancient roots in the stories of Saint Nicholas of Myra, a countercultural force, a figure whose principles are more important than his presents. Though he does love giving the perfect present.

In some ways, Gwenn’s perfection in the role is a liability: it is so easy to believe this man to be Santa Claus that Doris and Susan Walker (Doris especially) can seem to be dragging their heels needlessly. Natalie Wood’s Susan is a genuinely charismatic performance by a child actress. She has the range to not only emote successfully on screen, but even to play the part of a child who cannot act, as she does when she fumbles slightly her attempts to pretend to be inviting Fred Gailey to Thanksgiving dinner, or struggles to convincingly play a make-believe monkey. So I think to some extent she sells us on Susan as a real kid who would wrestle with the problem—a child who is so indoctrinated against Santa Claus that believing in him might spark an identity crisis. She also gets the slightly easier task of being the first of the two Walkers to open up to the possibility of Kris’s telling the truth, in famous scenes where she tests the reality of his beard or listens in as he effortlessly switches to speaking Dutch to offer greetings to a recently adopted refugee. Maureen O’Hara’s Doris has to be the rigid one, and it’s no criticism of O’Hara when I say that it does become just a little difficult to believe in a woman who refuses to let a primary schooler read fairy tales or pretend to be an animal for fun: I think that’s a challenge for the (admittedly Oscar-winning) screenplay, which has somehow to make this premise work, and if it’s stretched a little thin there, well, at some point we have to accept that this is a movie about Santa Claus and not a hard-hitting realistic drama.

The message of Miracle is, as I’ve noticed revisiting it as an adult, surprisingly complicated in its politics. The film seems to wear its anticapitalist leanings on its sleeve: you notice even as a kid that Kris courageously stands up for sending parents to get toys from other stores, and as you get older, perhaps you pick up on the fact that Macy and Gimbel only embrace the idea because they realize it’ll turn even more of a profit, and not out of any real belief in the ideal. Alfred, the sweetly naive custodian, observes mournfully early on in the film that these days the worst of the “isms” floating around the world is “commercialism”. It’s all “make a buck, make a buck,” even in his native Brooklyn, he laments. Fred Gailey throws away his job for the sake of a higher principle, and Judge Harper risks his chances at re-election for the sake of his own principles (somewhat different from Fred’s). And yet. This is also a movie that never really takes Macy or Gimbel to task—to the contrary, you’ll come away from the movie feeling a great deal of sentimentality and even sweetness in connection with “Mr. Macy”, a person who did not exist (at least, not in 1947, by which time no Macy had owned the company for over half a century). It’s a movie that treats the material desires of its characters as laudable: nobody is ever told that the “real meaning of the holiday” is something other than getting the right present, and even the movie’s final climactic moment of awe-struck belief is something only occurring because a character thinks she’s just been “given” an extraordinarily expensive “gift” (that others will have to work rapidly behind the scenes to actually buy for her). This is a movie about faith, yes, and love, but it’s one that has no problem assuming that these things can co-exist happily with thriving post-war American commercialism and not encounter the slightest trace of a conflict. This is odd for an American holiday movie: we just don’t tend to think about it because for most of us we can’t remember a time when this movie wasn’t a Christmas classic.

To be clear, I am in sympathy with this film’s moral compass to a large extent. The truly odious Sawyer, who at the film’s start is an industrial psychology staffer for Macy’s, is a monster measured along any possible axis: narcissistic, cruel, misogynist, selfish, and vindictive. Violence may not be the answer but I can’t claim to be disappointed when Kris Kringle beats him over the head with an umbrella. Kris is a huge proponent of learning to love not only yourself but those around you, whether it’s getting Susan to realize that she can connect with the kids playing in the courtyard or opening Doris up to the idea that romance hasn’t passed her by forever. I like that: who wouldn’t (other than Mr. Sawyer)? And the movie is a huge believer in accidental grace, which I love as an undercurrent: good things happen despite people’s intentions rather than because of them. Doris Walker and Mr. Shellhammer hire a Santa Claus thinking he’ll be good for business, not for their hearts. Macy and Gimbel help beleaguered parents as a marketing scheme. Even the movie’s most famous sequence, the arrival at the courthouse of an endless stream of letters to Santa Claus that win Kris’s freedom, is of course the self-interested action of two overwhelmed postal employees who have realized it’s a pretty slick solution to an overcrowded warehouse. This is a truth about the world, and the ways in which goodness manages to survive even among people who are not trying in any particular way to be good. It makes me smile.

I know this review’s running long, and it’s a holiday weekend, so I’ll stop here, though I could say a lot more about this film: it’s a rich text and there’s a lot to find (and like) in it! To me, again, the movie undeniably does what it sets out to do basically perfectly—you wouldn’t think that you could merge a fantasy about Santa Claus working in a department store with a surprisingly high-minded courtroom drama, but it works incredibly well. I think what ultimately leaves me just short of calling the movie a masterpiece is my sense that its message isn’t quite profound enough for me. When Kris tells Fred, early on, that “those two [Doris and Susan Walker] are a couple of lost souls, and it’s up to us to help them,” that feels really true in my heart. And it’s weird to realize, at the end of the story, that they accomplish this by means of Fred dating Doris (I’m sure he’s a nice guy, but how is this “saving her soul”?) and Kris persuading Doris by means of his sincerity and Susan by means of an incredibly unlikely gift that he’s the real Santa Claus. They have learned to be a little less hard-headed about the world, but not in a way that feels inspiring to me, let alone soul-restored. It’s a sweet movie, a holiday treat, and I could watch Edmund Gwenn chew bubble gum or sing a song about Sinterklaas any day of the week and be happy about it. But it’s not a fable that speaks to my heart at quite its resonant frequency. If it does that for you though, dear reader, I am genuinely and unreservedly delighted for you, and I’m certainly happy to celebrate it as a worthwhile member of the Christmas motion picture canon here at the start of the FFTH season.

I Know That Face: Jerome Cowan, who in Miracle appears as the district attorney, Mr. Mara, plays the role of Fred Collins in 1950’s Peggy, a movie set around the Tournament of Roses Parade that rings in the new year in Southern California. Percy Helton, who here performs uncredited as a Santa Claus so inebriated that he’s pulled off the Thanksgiving Day parade float, makes a similarly uncredited appearance as a train conductor in another midcentury holiday classic, White Christmas, which I covered last year on the blog. And Alvin Greenman, memorable in his uncredited role as the sweet and simple young Alfred, is the only member of the 1947 film’s cast to appear in the 1994 remake: in that movie, he plays a doorman (also named “Alfred”).

That Takes Me Back: It’s a little wild when Doris tells Shellhammer that she won’t miss the parade since she can see it from her apartment building: this is near the very end of the era in which a person could not watch the parade on television (it was first televised locally in New York City the year after this film was released, and has been televised nationally since 1953). I think of these parades so much as a television spectacle that it’s kind of amazing to consider the decades in which they were an in-person only event. Susan saves her chewing gum overnight, which is kind of amazing to me: I remember doing that as a kid, but gum is such a cheap commodity that I’d never think of doing it now. I wonder if it’s just my age that affects this (or my income), or if this is something nobody does anymore? Would a modern kid relate at all to the song “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose Its Flavour (On The Bedpost Overnight)”?

I Understood That Reference: In terms of references to other Christmas stories or media, obviously this movie is chock full of Santa lore. There are references to the North Pole, of course, and Kris Kringle’s next of kin on his employment card consist of all eight reindeer (including the accurately spelled “Donder”). Donder’s name will be permanently altered in the public memory in just two years after the release of the song “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” which refers to him as “Donner”. Rudolph’s omission from a Santa film is probably also a “That Takes Me Back” moment really—though the character of the scarlet-snouted reindeer who guides Santa’s sleigh had been created back in 1939, it’s not until a 1948 cartoon short and the 1949 song that he springs into the limelight so completely that he’ll be inextricably tied to Santa from then on.

Holiday Vibes (9/10): From the parade that (for many of us) kicks off the holiday season to a party with not one but two Santa Clauses dispensing gifts next to an enormous and lavishly decorated tree, this movie touches on so many aspects of the season (busy department stores, children making lists of desired gifts, etc.). And, as with a few other true classics, I just think this film is so embedded in my memory that even its less Christmassy elements are associated with the season somehow, from Mrs. Shellhammer and her triple-strength martinis to Fred Gailey’s facts about the United States Postal Service. It maybe doesn’t hit on every single element I’d look for in a holiday movie but it does really well on this front.

Actual Quality (9/10): And again, I don’t want to be mistaken: it’s doing a great job on the “quality” front, as well. Despite my critiques, I think it’s a really well-crafted piece of entertainment, and one with a lot of heart—it more than deserved three Academy Awards and a Best Picture nomination, and it’s a worthy addition to the list of films that we treat as more or less mandatory to be shown and shared at Christmastime. That scene where the mail shows up at the courthouse is thrilling every time.

Party Mood-Setter? A film so familiar to so many of us more or less HAS to work in this setting—especially because it’s a movie with key moments you can check in for and then a lot of fairly low-key scenes that work fine in the background of cookie decorating or catching up with old friends. It’s better if you pay full attention but it is very pleasant company if that’s all you’re after.

Plucked Heart Strings? I’d say we get close, in a moment or two, where Doris’s faith in Kris is sincere and that’s moving, but it’s more a fantasy story than it is one that wants a lot of sincere heartfelt emotion.

Recommended Frequency: Oh, come on now, you know this is an every year kind of movie, or at least it sure is for me. If you’ve somehow made it this far in life without seeing it, it’s time to dive in. If you haven’t watched it since you were a kid, I think you’ll find it bigger than you remember: how much you find yourself connecting with the themes it advances will obviously vary, but I think it’s a movie that rewards re-watching, and I hope you’ll give it your time this holiday season.

Luckily for you, it should be fairly easy to watch Miracle on 34th Street. Right now, it appears to be streaming for subscribers on Hulu, Disney+, and Amazon Prime Video. If you want to rent a streaming copy, it looks like Google, Apple, and Fandango at Home would all be happy to help you out (for a small price). Barnes & Noble will gladly sell you a copy on Blu-ray or DVD, and Worldcat’s data suggests that nearly every conceivable library system has access to a copy if you just want to borrow one.

One thought on “Miracle on 34th Street (1947)”