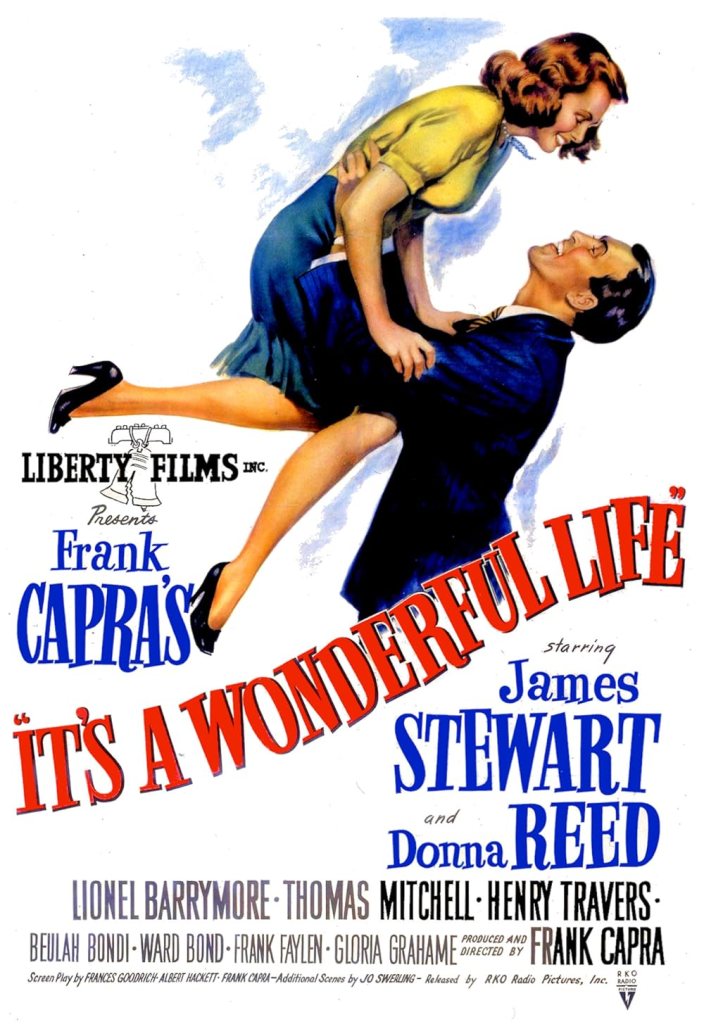

Review Essay

It’s so hard to talk about It’s a Wonderful Life, since for some of us every single scene is imprinted on our memories from childhood, the strangeness and wonder of this fable about life and hope and worth so indelibly associated with Christmas that it would be very difficult to say anything new or original. And for others, the film is unfamiliar — a “holiday classic” but one that’s long enough and black-and-white enough that you haven’t picked it up yet, perhaps especially because the movie’s fans tell you it’ll put you through the emotional wringer and that’s not necessarily something we all want to sign up for. What can I say about a movie many of you have either memorized or else long avoided? Well, it’s Christmas Eve and I guess there’s no reason to say anything other than what I think and hope it connects with you, wherever you’re coming from. If you’ve come here to spend any of these important holiday minutes with me, I owe you nothing less.

The premise of this film is well known, I think: a man named George Bailey is shown the world as it would have been without him, as though he was never born, and it transforms him. And it has something to do with Christmas, though I imagine when folks who’ve not seen it hear these summaries, it’s always a little puzzling what the connection really is. So, I’ll offer a different way of seeing this film, if that’s all right. The author of the short story on which this movie is based always acknowledged a debt to Charles Dickens and A Christmas Carol, and I think it’s evident here: the movie’s three great sections are George Bailey’s Past, Present, and a grim vision of what will become of the world without him (though, of course, to be precise, it’s the world as though he had never been). George is no Ebenezer Scrooge — the real “covetous old sinner” of this piece, Scrooge’s counterpart, is the malevolent spider in his web, Henry F. Potter, whom this film can neither explain nor redeem. Instead, our attention is on an ordinary man in so many respects, both kind and hot-tempered, both ambitious and loyal, a good man and a flawed one. We see him at his triumphs and at his most desperate. And so we learn alongside him as people more able to put ourselves in his shoes than most of us can ever fit into Scrooge’s. It’s a carol for an American life.

It carries with it that same background of Christmas religious observance that Dickens employs in his novella: we open on a snowy Christmas Eve in the town of Bedford Falls, and all we know is that behind every closed door and window, simple and heartfelt prayers are being offered for a man named George Bailey, whom we have not yet seen. And then, in the movie’s weirdest device, we are in some astronomical photograph, as blinking galaxies and stars represent God, Joseph (whether an angel or the adoptive father of Jesus is unclear), and of course, Clarence Odbody, AS2 (Angel, Second Class). Clarence is tasked with assisting George Bailey out of a terrible condition — far worse than being sick, God observes, George is discouraged. He is contemplating suicide. The next hour and a half, then, unfold for Clarence the life of George Bailey, with a particular emphasis on Christmas Eve, 1945, the day of George’s profound despair, as this novice angel tries to “win his wings,” a metaphysical situation that is never really explained further.

I think what must surely be challenging or even off-putting to a new viewer is the character of George Bailey himself — Capra plans to take full advantage of the fact that, as I observed in writing about The Shop Around the Corner, Stewart had developed this screen persona by the 1940s that allowed him to play characters who were irascible and difficult and rude without losing the audience’s trust. Capra extends that quality down into the boy actor playing the younger version, as from the beginning we understand that George is brash and ambitious and self-confident to a fault…but he’s also wise beyond his years at times, and loyal to his sense of ethics, and always willing to make a sacrifice for someone in need. It’s why he taunts his kid brother Harry into a daredevil sled ride that forces George to leap into an icy lake to save him. He’s condescending about coconut and bragging about his membership “in the National Geographic Society” but one glance at a telegram and he realizes his boss is grieving — and he risks anger and even violence to save Gower, the druggist, from his own despair. Those scenes are hard to watch, but what’s hard to watch in them is what’s most human — some of us have known griefs as profound as Gower’s, a pit so deep we cannot see out of it, in which every human voice wakes further to agony. Some of us have had to be as brave as George, standing up to someone’s pain knowing it may cause us pain, ourselves — for the sake of helping them, of helping others. The emotions that come home in the movie’s justifiably famous closing scene are all laid in us here, bit by bit, as George’s life unfolds. We come to care about the people he cares about, and through them, we care for him.

If you’re a newcomer to this movie, please don’t feel it’s all death and sadness: there’s a liveliness to so much of the film. We get it from the banter of Bert and Ernie, the policeman and the cab driver (no, despite Internet rumors to the contrary, as far as we know Henson did not name two roommates on Sesame Street for these men). It shows up in the Bailey home, with criss-crossing dialogue and Harry balancing a pie on his head and Annie, the family’s maid, very rightly referring to the Bailey boys as “lunkheads”. Even if you’ve never really watched the film, I’m guessing you might know about the Charleston contest, as George and Mary accidentally dance their way into a swimming pool. What’s great about their flirtations that night is that George is just as complicated as ever, but Mary sees through him to the man he’s going to become. She’s not planning on “fixing” George Bailey, but she knows better than he does who George Bailey really is. What I love about the movie, though, is how it weaves its deeper ideas into the fun moments. Ernie the cabbie is George’s wisecracking friend, but it’s also a loan to him that becomes a rhetorical football between George’s idealism about the common man and Potter’s domineering sneers about the working class’s need to learn “thrift”. The chaos of that dining room scene at the Baileys surrounds a really serious conversation in which Peter Bailey (who, without knowing it, is having the last conversation he’ll ever have with his son) tries to convey to George what matters in life…and George both knows in his heart his dad is right and doesn’t want to give up his dreams for it anyway. And of course, George’s relationship to Mary is the hinge on which the whole movie turns, at every step.

I’ve heard complaints about the movie, over the years, about the ways it handles some gender dynamics, and I won’t defend any 1940s movie as wholly innocent of those charges: we just know better now, or at least some of us do. This is, I should note, still a lot better at giving women agency than much more modern films like Ghosts of Girlfriends Past, but that’s a low bar to clear. I do think, though, that sometimes those critiques have been misplaced. For instance (and apologies for spoilers, but so much of this movie’s success is about its final half hour that I cannot avoid them all), Mary Hatch doesn’t end up an “old maid” librarian because the movie’s punishing her for not having George in her life — this is what she’s said from the beginning, telling George at one point very plainly that if it hadn’t been for him, there wasn’t anyone else in town she wanted to marry. And the movie’s also not arguing that being an “old maid” or a librarian is a fate worse than death — it’s a fate that feels like death to George, because it IS his death. Or rather, it’s damning proof that Clarence is right, and that this is a world in which he was never born, never did anything, never kissed Mary Hatch Bailey on their wedding night or built a life with her. It’s not Mary he’s grieving: it’s himself.

I’ve heard complaints also about George’s outbursts at his kids, and certainly I can understand that depending on your own experiences, it may be very painful to watch the movie’s “hero” act so dismissively and harshly to his children, shouting at them and smashing things. I don’t want to minimize the harm there, but again, I think the movie doesn’t either. That Christmas Eve, George is facing the ruination of his entire life — he sacrificed everything for the sake of Bedford Falls and the building and loan, and now the business will fail and the town will slip into Potter’s cruel hands and his own family life will be destroyed by scandal and prison, he expects. He’s barely holding it together until those moments when he’s not holding it together at all. But I think it’s clear from the ways the children react that this is not the father they know — that they expect support and love from him, and it is a startling betrayal to find those things missing. That doesn’t make an evening of borderline abusive conduct “okay”, but I think it reframes the situation for us — we have to believe that we’re seeing a man prepare to commit suicide because he believes the world is better off without him. So he has to wreck himself and that family’s peace enough to have that moment where he’s stammering apologies and trying to command them to restore the home he’s terrified of losing, and his wife and children look at him with such fear that he feels they’ll be happier without him. It is not the well but the sick who need a doctor, as the Gospels remind us: for George Bailey to be saved, he’s got to realize the harm he’s done. If you don’t want to roll with that, I get it. But for those of us willing to take that journey with George, it’s the movie’s power.

I refuse to spoil any more of the movie’s final half hour, much of which plays out like a Twilight Zone episode, but of course it’s a Twilight Zone episode that follows 100 minutes of establishing scenes, so that we know every single minor character on screen and we can feel the depths of George’s confusion and ultimate agony as he explores a world without him in it. The movie’s values are on its sleeve throughout, and say what we will about Capra, he understood what endangered American freedom and joy. It’s what endangers it still. This sequence is an indictment of Potter, and of a society resigned to letting the Potters of the world have their way. And the whole time, I know, a new viewer will keep saying to themselves, “okay, this is all happening on Christmas Eve. But where’s this movie that’s supposed to be so holiday-inspirational that it moves me to tears?”

And then you get the ten minutes that either work for you or don’t. If it’s too sentimental for you, too neatly resolved, too implausible, then I get it. There are other movies that maybe will kindle hope for you, if hope’s something you’re willing to take from a world that rarely seems to reward it. For the rest of us, this is where the movie breaks us open. I watched this film for what I am sure is at least the 40th time this December, preparing for this blog post. And I wept like a child for most of its final sequence, even though I could also probably recite it to you by heart. Gratitude is overwhelming like that, I think — when we confront the fact that we can be grateful for life even at its darkest extremes, even when we feel most lost. And what the film is urgent in reminding us is that we are more loved than we know; there is more joy than we’ve yet found. No man is a failure who has friends, as Clarence says, which is both glib and profound. I get that that’s not a comfort to everyone out there, but I hope that the movie’s argument speaks even to those who feel friendless, reminding them that any life has touched so many other lives, and we have given so much more love than pain, those of us who aren’t Potters, at least. Half the people we see in the film’s finale are not George Bailey’s friends. They are people who have known the worth of his life, and who are ready to return blessing for blessing. That’s the Christmas magic of this movie, and the reason that, despite being a film that spends only about half its running time on Christmas Eve and very little of its Christmas Eve time doing anything that feels connected to the holiday, it remains not just a holiday classic, but to many folks THE holiday classic, the film we cannot do without. It’s so powerful for me that there have been Decembers I couldn’t take watching it, because it would have hit me too hard. Whether or not it’s that kind of movie for you, I wish you this movie’s sense of gladness and of hope, of joy at being alive, of the discovery of friendship and fellowship in those places in your life you least expected them. For those preparing for Christmas or Hanukkah tomorrow, or Kwanzaa the next day, or simply preparing for a break in life’s chaos here at the turning of the year, peace to you, and thank you for reading this little blog.

I Know That Face: Henry Travers, who here plays the angel Clarence Odbody, plays the businessman Horace Bogardus in The Bells of St. Mary’s, one of those movies that has a Christmas sequence and is therefore a holiday movie, as well as playing Matey, the brother to Anne Shirley’s landlord, in Anne of Windy Poplars…another movie that has a Christmas sequence and is therefore a holiday movie. Ward Bond, who here plays Bert the policeman, plays a different kind of cop in 3 Godfathers, a loose Western retelling of the three wise men (and at least partial inspiration for Tokyo Godfathers), in which Bond plays Sheriff Buck Sweet. And of course we’ve already seen Beulah Bondi, here Mrs. Bailey, in Remember the Night, as well as Jimmy Stewart, here our George Bailey, in both The Shop Around the Corner and Bell, Book and Candle.

That Takes Me Back: As someone who remembers being mesmerized by the spinning of a record on our record player, I love the sight of the phonograph that, while playing, can also turn the spit to roast two chickens on George’s wedding night. My guess is that my daughter would barely understand the phrase “a long distance telephone call” other than from context clues, and therefore would have absolutely no chance at understanding what it means that Harry’s “reversing the charges”. Some things have changed a lot since I was young. This is where I’d normally make a quip about how the movie takes me back to when we held greedy, amoral men with too much money and absolutely no conscience accountable under the law, but in this case there’s nothing at all nostalgic about It’s a Wonderful Life — Potter seemingly will get away with having stolen eight thousand dollars from the Baileys, and go on being the man in Bedford Falls with the most power and capital, even if Harry Bailey is right (as I hope he is) in calling his brother George “the richest man in town,” speaking on a human level.

I Understood That Reference: Speaking of Henry Travers’s filmography (as I was just a moment ago), we see in a couple of shots that The Bells of St. Mary’s is playing at the theater in Bedford Falls that Christmas Eve. Tommy is, I think, wearing a Santa mask when he tries to scare his father and George in his panic doesn’t know what to do other than hug him frantically…but honestly, I could be misreading it, it’s a weird mask.

Holiday Vibes (7/10): This is another one where there’s no easy rating: give it a 10 and a new viewer will, 45 minutes in, wonder what the heck is so Christmassy about it, but give it some low number and that’ll underplay how powerfully this movie’s scenes and its message have taken up residence in millions of people’s experiences of December and the holidays. I think a 7 is fair, given that half the film’s on Christmas Eve, and we encounter enough of it (from decorations to music to the movie’s themes) that it’s playing an important role. Plus the big finish. Knocks me flat, every time.

Actual Quality (10/10): This film has, for some reason, long had a reputation as being underappreciated by critics, but I don’t think that’s true — sure, a few pieces have knocked it for its sentimentality, but it was nominated for a bunch of Oscars, and in recent years it has placed high on almost every kind of movie list from the organizations that put these things out on both sides of the Atlantic. For me, it’s absolutely top tier: those of you I’ve made aware of Flickchart are probably asking where this one ranks, and while it’s moved around a little over the years, I think it’s solidly a top 25 movie for me (and it’s currently sitting at #20). But the movies I love aren’t always the ones I think have the greatest quality, so let me double down here on this movie’s artistry: the cast is tremendous, and the film successfully sweeps us through half a century of American life, touching on the influenza epidemic, the roaring 20s, the crash that started the Great Depression, the second World War, etc., without feeling cheap or cheesy in the ways it uses those contexts. It is hard to pull off this movie’s intended outcomes, mixing some comic moments with a classic romance featuring two stars but wrapping all of it in one of the most fantastic premises you’ll find in a major Hollywood release of that era. The fact that it succeeds on all fronts leaves me feeling there’s no way I can dock it even half a point.

Party Mood-Setter? So, it really shouldn’t work in this setting, since the film is complicated and has a pretty wild premise, and then the emotion at the end hits like a truck. But I’d be lying if I said there weren’t households that know this film so well that it can be a Christmas vibe you’re only half paying attention to — how many of us, indeed, remember Christmas Eves where this movie was just on in the background while our families did other things? If it works that way for you, though, you’ll already know it: for folks newer to the movie, I wouldn’t recommend using it in that fashion.

Plucked Heart Strings? I know sometimes we say things like “I cried” and mean them only metaphorically, so I want to be clear: I cried human tears while rewatching this. A lot of them. Tissues were involved. I think it may have hit harder because it’s 2024 and I have a lot of feelings about the Potters of the world and the bravery of communities banding together to protect each other from them. It may also have hit harder just because I was thinking in such detail about the film that its themes really reached me. But I think it’s also just a movie that does this to people — I ran into a “reaction video” on YouTube about It’s a Wonderful Life, where a woman (I think a Millennial) filmed herself watching it for the first time. Yeah, I know, I don’t really get this genre of video either, folks, but I was curious. She got within about 5 minutes of the end and was remarking at how confused she was that her viewers had told her she’d cry at this movie, because it just doesn’t hit like that. And then she spent the last five minutes in full, heaving sobs as the movie came crashing down around her — it hit her so hard that afterwards, in conversation with her off-screen partner, she tells him she feels so embarrassed by her reaction that she’s not sure if she should post it. I share all that just to say, I think that’s how this film works. It surprises us with joy in a way that gets past our defenses. Maybe it doesn’t hit you like that, but I’d come to it, if you are approaching it for the first time or the first time in a long time, ready to let yourself feel this way.

Recommended Frequency: As I mention above, to me, this is only kept off of the “every single year” list by the fact that it’s powerful enough to be hard to take some years. It’s still easily a 9 out of 10 years movie for me, and if you’ve not seen it even in just the last few, I’d tell you you’re overdue. I hope you get a lot of joy out of it.

Before I tell you about where you can watch this movie, I do want to note: this is the last Film for the Holidays movie review of 2024. It might be the last one ever! But the day after Christmas, if you want, I’ll be posting a survey here. It’s intended to get a better understanding of what the blog’s viewers might care about if I was thinking of doing this again — what to keep the same and what to change. It’ll be very short and obviously totally up to you which questions to answer if any. But I hope, if you’ve come here at all regularly, you’ll pop back here and tell me what you think: even if what you think is “yeah, James, failed experiment, use your free time for something else”.

If you want to watch It’s a Wonderful Life, you can go very old school and watch it over the air tonight, Christmas Eve, on NBC at 8pm Eastern / 5pm Pacific. You can stream it on Amazon Prime if you’re a subscriber, or stream it for free (with ads) on the Roku Channel or Plex. It looks like you can rent it from Google Play or Apple TV or Fandango at Home (as well as Amazon, I expect, if you’re not a Prime subscriber). This is a classic, folks, and if you want to own it, I think you should — Blu-ray and DVD copies are really inexpensive (in my opinion) at Barnes & Noble right now. And of course Worldcat assures me it’s in thousands of libraries, so I think you should go check out your local library’s film collection.

If you don’t swing back through here for the survey, folks, it was a delight sharing this journey from Thanksgiving to Christmas with you. Whatever holidays you are or aren’t celebrating, I appreciate you giving me a little time during a stretch of the year where free time is often hard to come by. Perhaps I’ll be back in 2025 and so will you, but if either (or both) of us are not, happy film watching to you, and a happy new year regardless!

6 thoughts on “It’s a Wonderful Life (1946)”