Review Essay

Some of my favorite holiday movies make the list because of the depth of their ideas: they make me think the way I want to think at this time of year. But others make the grade purely because of the power of their feelings: they just evoke an emotional response in me that feels like the holidays, regardless of what the underlying film intends to convey. The latter category is, I think, the best way for me to broadly characterize White Christmas, a motion picture that surely most if not all of you are very familiar with: I love this movie, I watch it every Christmas, and if I think about it too much, I start to wonder why I have such a deep connection to it. Let’s try to unpack both sides of that, shall we?

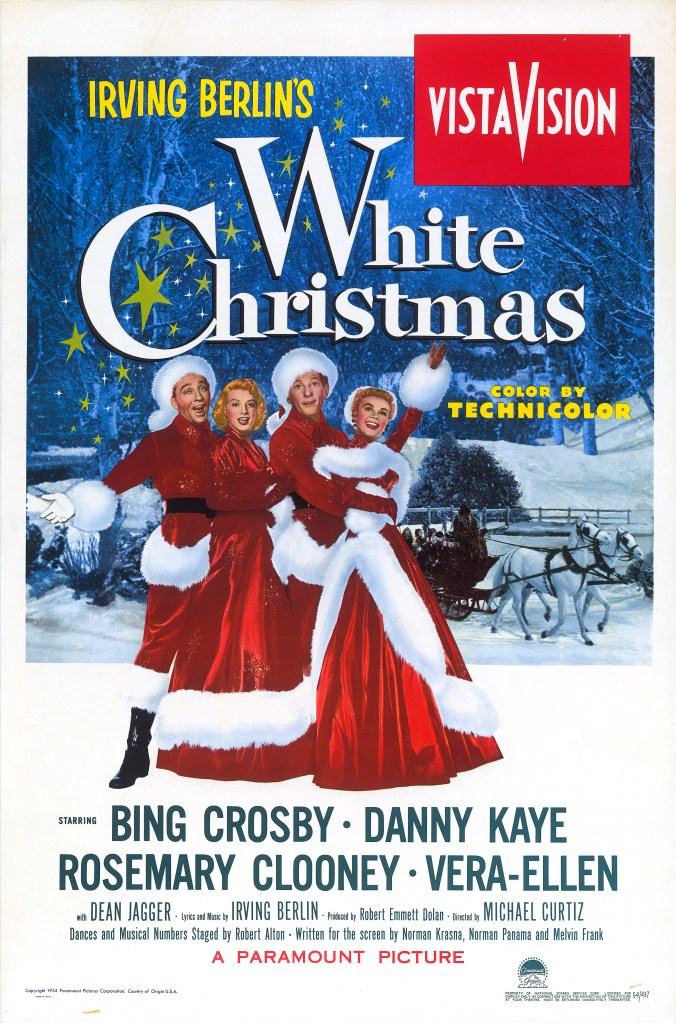

First, the basic premise, in case somehow this movie’s missed you in the past: the movie opens on Christmas Eve, 1944, with two soldiers (one an already-famous entertainer named Bob Wallace; the other an ambitious but green up-and-comer named Phil Davis) putting on a show in honor of their general and Christmas (seemingly in that order) before an artillery assault breaks out and Davis saves Wallace’s life. Having done so, he extracts a series of promises from Wallace — to sing a duet together, to become partners, to start producing big musical revues — before they cross paths with the singing Haynes sisters, Betty and Judy, and find themselves (through a mishap or two) following the girls to Pine Tree, Vermont. There, they discover their old general is a down-on-his-luck hotel owner in a snowless and therefore guestless December, and the boys spring into action to come to his aid (while Phil and Judy try to steer Betty and Bob into each other’s arms). Along the way, there’s a lot of singing and dancing from some of the most talented folks in Hollywood at midcentury: there’s a reason this film endures.

One of the things I noticed on this latest viewing is how the film repeatedly has these men make a promise with mostly good intentions but lacking in a little sincerity…and then that promise turns out to be really meaningful to them in unexpected ways. Wallace promises Davis to sing a song with him out of guilt more than enthusiasm, and his whole life changes. The two of them decide to keep faith with a weird dude they knew in the Army out of obligation, and that’s how they meet the Haynes sisters. Davis’s promise to find Wallace a girl is motivated by a selfish desire for a little leisure time, but, well, other good things come of it for him. I don’t think the film’s message is “do the right thing for the wrong reasons and you’ll succeed” but there’s definitely something going on there, under the surface.

Another element that’s definitely going on under the surface is social and cultural conservatism — this movie is fully locked into the moral landscape of mainstream America in the 1950s, and the “boy, girl, boy, girl” lineup of romance and matrimony fits a little too neatly. The implication that marriage is the most central meaning in life is pretty clear. The valorizing of the army is understandable for the era, but it’s over the top nevertheless: the movie’s absolutely not interested in a depiction of war or its aftermath that feels genuine (unlike say, The Holly and the Ivy, which I wrote about here just two days ago). And not one but two musical numbers take swings at modern entertainment — “Choreography” memorably parodies modern dance (I think specifically the Martha Graham Dance Company) in making an argument that the old tap dancers and soft-shoers were obviously superior. And, of course, the medley that ends with “Mandy” repeatedly reminds us that the performers REALLY miss those old-fashioned minstrel shows — weren’t those the good days? For my part, I think MGDC is fine as a target — yes, there’s something a little sneering about that number, but it’s also pretty funny, and I am unaware of any weird bigotry associated with Martha Graham’s particular style of modern dance. Minstrel shows, on the other hand, were a real blight on American entertainment — Bing Crosby, of course (who plays Wallace here), had appeared in blackface in a minstrel number in an earlier film, Holiday Inn, so he’s only thinking back about a decade as he yearns in song. And of course the thing that’s ridiculous about both numbers here in White Christmas is that they are self-refuting — sure, the modern dance in “Choreography” is intentionally goofy in ways that make me laugh, but doesn’t that suggest that in fact the new modern dance style was capable of pretty evocative communication and therefore artistry? And more importantly, doesn’t the fact that Clooney and Kaye and Crosby can joke around in song on stage, before Vera-Ellen comes out and dazzles us all with her skill as a dancer, prove that you can have all the old vaudeville fun you want on stage or screen without burdening it with awful racist caricatures? We do not need “Georgie Primrose”, as the song here suggests, to have a good time: far from it, in fact.

I know, I know — none of this sounds like me being in love with this movie enough to watch it every Christmas. Well, I haven’t really dealt yet with the four stars of this movie, and I have to say, each one of them is basically ideal casting, simply ideal. Bing Crosby is just coming down from his apex of fame and talent here in the early 1950s: the film needs a proud but affable crooner and that fits Bing to a T. His ability to work as a straight man had been pretty carefully honed, and for my money he is JUST young enough to still be playing a romantic lead in this film. His comic foil, Danny Kaye, is a personal favorite of mine — Danny’s effortless and energetic presence on screen really never fails to make me laugh or hold my attention. Everyone’s tastes are different of course — I complained back in my review of The Holiday about Jack Black dialing it up to 11 a little too often, and I’m sure there are folks who would feel the same about some of Kaye’s goofiness here, but for my money he can dial it up as high as he likes, I’m here for it. As young Judy Haynes, Vera-Ellen is startlingly talented in every kind of dance she’s asked to perform — so good, in fact, that Kaye couldn’t keep up with her (if you’ve ever wondered why that one semi-anonymous dude is suddenly dancing with Judy in a couple of big numbers, it’s because he was a top-tier studio dancer covering the parts that Kaye, despite all his talent, just couldn’t do himself). And I love the way she very subtly breaks the fourth wall — the next time you watch this film, pay attention to how many times Vera-Ellen makes direct eye contact with the camera, and flashes us a little conspiratorial smile as if to say, “God, I’m good. Watch this next bit.” Finally, Rosemary Clooney as Betty Haynes is, in my purely subjective opinion, just about perfect: she takes a role that, on the page, might be a bit stiff or stick-in-the-mud, and presents a woman who’s warm and guarded and winning. Plus she’s got the voice of an angel and she’s a vision in Technicolor in basically every perfectly chosen Edith Head costume — maybe you can take your eyes off her, but I can’t. And the end result of all four of them basically firing on every cylinder in every scene means that the film is always bursting with charisma, no matter how I feel about the writing or the pacing or the underlying message of any given moment.

And White Christmas is such a lush viewing experience too: I don’t know if any film’s color is more saturated than the reds and greens of this movie’s opening titles, and it’s paired with a really effusive orchestral overture. The heightened theatricality of everything about the film somehow works to its advantage, for me: there’s no question that every outdoor setting looks like a sound stage, from the “war zone” in 1944 to the “boat dock” where Davis and Judy first dance to the “parking lot” outside the Pine Tree Inn. But something about the artificial quality of those spaces just makes the whole thing feel slightly dreamlike to me in a way that’s really calming and satisfying. Add in a few incredibly catchy Irving Berlin songs and some scintillating Robert Alton choreography and I just fall in love with the film every time.

Am I falling in love with a holiday movie, though? For a film that opens and closes with two stirring renditions of “White Christmas”, the best selling single song of all time, I think there’s no question that this film is not all that connected to the holidays as far as its running time goes. We get about 10 minutes at Christmas Eve in 1944 (more than half of it about General Waverly and not the holiday at all). Then, while there’s some talk about the Christmas Eve looming at the film’s end, it’s not until the very last segment of the film that we get the holiday tableau you might remember, full of children in costume and Santa hats and the world’s largest Christmas tree. But what a tableau it is. Thematically…well, I’ve talked about this movie’s theme already, a little. The more I think about what I think this film wants to say, the less comfortable I am with it — I don’t think it’s a harmful film, to be clear, but I think it just has a different sense of what’s important and in need of defense than what I believe in. I have a hard time connecting most of the themes I do see to anything I would associate with Christmas in particular. In the end, though, I can’t deny that the power of the movie’s full force being directed at the Christmas holiday really connects for those brief stretches where it’s doing that. I come away fully washed in the VistaVision spectacle of the idealized midcentury holiday. There’s a reason a ton of us watch this film every year and feel Christmassy about it.

I Know That Face: Mary Wickes, who plays Emma here (the hotel’s housekeeper and professional busybody), has a couple of other holiday turns under her belt: she plays Henrietta Sawyer in The Christmas Gift, a TV movie starring John Denver and Jane Kaczmarek (what an eclectic cast, eh?), and near the end of her career, she plays Aunt March in the 1994 edition of Little Women, another one of those movies that feels like Christmas far more than it is actually set at Christmas. And Bing Crosby, here playing the seasoned entertainer and mogul Bob Wallace, is Father Chuck O’Malley in The Bells of St. Mary’s, a film that has a long enough sequence set at Christmas that it tends to make lists of holiday movies (and would certainly be eligible for this blog). Bing, too, sang in that famous televised “Little Drummer Boy” duet with David Bowie that I alluded to when I reviewed Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence.

That Takes Me Back: Man, as a long-time happy Amtrak traveler (in the days when I could sleep sitting up overnight in coach: ah, youth), the vision of trains full of sleeper cars rolling through the night is nearly irresistible. I loved, too, that in their conversation about whether to take the train or the plane, it’s clear that the train is luxury travel (since you can sleep), whereas on the airplane you’ll wind up sitting up all night. No kidding, Bing. It is fun to see the Haynes sisters have to fuss about their phonograph records (and phonograph) they travel with: technology has changed our relationship to music in so many ways. And I know that I will never in my life get to say, as Bob Wallace does, “Young lady, get me the New York operator.” And that’s okay, you know? But I do kind of wish I’d gotten to do it.

I Understood That Reference: The only Christmas story I heard them alluding to was a quick throwaway line when Ed Harrison tells Wallace he wants to show them off “playing Santa Claus to the old man,” right before Bob says to knock it off…though not in time to keep Emma from getting entirely the wrong idea about the situation.

Holiday Vibes (5.5/10): There is absolutely no way to score this film. For those of us who watch this with religious attention every single year, it would seem ridiculous to set this any lower than a 9.5: when I hear the conductor calling out “Pine Tree” and the gang starts riffing on how they must be in California and not Vermont, it feels like Christmas to me and a few million other people, but that’s pretty silly, isn’t it? And for those of you new to the film, I can easily imagine you, ⅔ of the way through, wondering if Christmas will matter to it at all other than that one opening scene you’ve already forgotten. 5.5 feels like the most honest middle ground I can offer to a movie that’s not about Christmas at all for all but about a half an hour, but those 30 minutes (distributed around the film a little) are incredibly evocative.

Actual Quality (9/10): Again, this is not a measure of how much I love it, but of how good the film is in my opinion. And I would say that I think the screenplay’s pretty wobbly here, in terms of actually pacing things out, delivering the scenes characters need, etc. But everything else — the aforementioned costumes and music and choreography and acting, and I didn’t even mention the really successful direction (from my perspective) by Michael Curtiz whose name you may recognize from little films like Yankee Doodle Dandy and something called Casablanca? There’s a reason the film works despite having a plot that’s kind of barely there, and it’s because the creatives in every other capacity are bringing their A game.

Party Mood-Setter? You mean, is this a perfect background for your holiday festivities? 100%, as long as you don’t find the minstrel number too weird — again, my only quibbles here are with the writing, but if you want to be baking or decorating or hanging with family while occasionally tuning into a fun song or a sweet dance number or just marveling at a perfect outfit, this movie has your back.

Plucked Heart Strings? I’ll be honest: I find Betty and Bob’s connection emotionally investing, but I definitely don’t get choked up here. I get a smile out of seeing the positive resolutions later in the movie for multiple characters, but there are never tears in my eyes.

Recommended Frequency: I can’t tell you it has to be in your annual rotation, but it’s sure in mine and permanently. And honestly, if you’re an appreciater of the genre of holiday movie (to the extent that there’s a good definition of such a genre), I just think this is going to be on your list already. It’s too beautiful to look at, with too much talent to watch and listen to. If somehow you’ve never seen it, I sure think watching it these holidays would be the right thing to do: I hope you enjoy it, if so.

To watch this holiday classic on streaming, Amazon Prime members have access via that subscription; it looks like if you’ve got some premium add-on subscription at places like Sling or Roku or AMC+, you might have access also. You can rent it, also, from all the usual places. Amazon will sell you the movie on disc — and with this year being the 60th “diamond” anniversary, let me tell you, there’s a sweet deal on a three disc combo pack that adds in some TV appearances by cast members, along with commentaries, etc. Worldcat says every library on the planet has this movie on DVD (okay, they say it’s close to 1,500 libraries, but that’s huge when compared with literally every other movie I’ve checked there for this blog).

3 thoughts on “White Christmas (1954)”