Review Essay

It has been suggested (not unfairly) by some of this little blog’s faithful readers that I don’t have much sympathy for mean-spirited movies. My relatively harsh reviews for films like National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation, Mixed Nuts, and most recently Scrooged do seem to bear that out: I didn’t respond well to the tone of any of those films, which all felt to me like they were dragging me in unwillingly as an audience member to participate in some downward-punching humor. Well, I didn’t place this film on the slate for this year thinking that it would offer a counterargument: in truth, I’d never seen it, and in my head I had imagined it would provide a little more solemnity, a perhaps slightly stiff historical drama to give some restraint to this final weekend before Christmas and the end of the blog season. Well, boy, was I wrong…but the fiery, aggressive, and (yes) mean-spirited film I got gave me a lot to delight in. I’ll see if I can explain why.

The premise of The Lion in Winter (a film adapting a stage play of the same name) consists of complicated family politics unfolding at a difficult Christmas gathering…only, unlike most films of this kind, the gathering occurs in a medieval castle (Chinon, in what is now France, for the Christmas feast in 1183), and the family’s internal politics govern the control of most of Western Europe. The family in question is that of Henry II, one of the Plantagenet kings of England, who by might and savvy and deft diplomacy had maneuvered himself to such heights that by this Christmas, he styles himself the Angevin Emperor: at the age of 50, he is a man who knows that his time grows short, and his legacy needs to be provided for. “I’ve built an empire,” he says early on, “and I must know that it is going to last.” Now that his eldest son is dead, he’s left with three potential heirs, and he invites all of them (Richard, Geoffrey, and John) to Chinon for the feast, knowing each of them thinks they can plot their way to the crown as his successor. Invited, too, is the boys’ mother, Henry’s rich and powerful queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, whom he has kept imprisoned in Salisbury Tower for many years now as he’s followed his heart in pursuit of other women: Eleanor may be here as a temporarily paroled prisoner, but she is still Henry’s equal as a politician and a schemer. Henry will, of course, have his mistress there, too: young Alais is her own complication, since she’s formally betrothed to Richard, but Henry has no intention of giving her up. Alais’s half-brother, though, the teenage King of France, Philip, will be at this gathering also, and he intends to force the matter of her marriage or else demand her dowry back from Henry. And you thought your family’s Christmas dinner conversations took place on thin ice, eh?

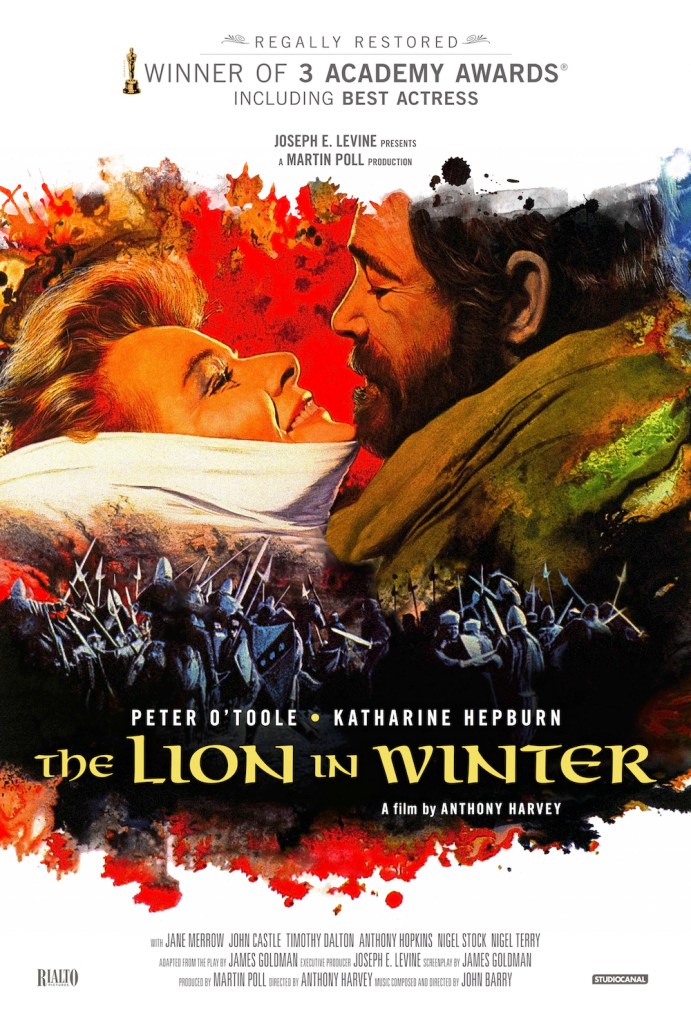

You might think, upon reading this still-insufficiently-detailed summary, that this will be far too complicated a web to make sense of as a viewer (especially if you’re not really up on your 12th Century politics) and that could be true for some, I’m sure. But I think the film works far better than you’d expect for a couple of key reasons, and the first is the strength of the acting. When you put Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in the hands of Peter O’Toole (then at the height of his powers as an energetic British leading man) and Katharine Hepburn (nearing the end of her dominance as a midcentury actress, but still capable of enormous screen presence at any moment, as proven when she wins her fourth Academy Award for this role), you give the audience a real gift: even when we can’t follow every detail of every double-cross, the sound and fury of these characters bears us along with the plot like a boat adrift in a flooding river. Add in a brilliant supporting cast—maybe none of them more scintillating than a young Anthony Hopkins as the brash juggernaut, Richard, whom we know best by his nickname, “the Lionheart”—and almost any dialogue would ring out like dueling swords.

It’s not just “any” dialogue, though: the screenplay (also Academy Award winning) is full of the most poetically intense exchanges, written for the heightened surreality of the theatrical stage, so much so that on film it borders on camp (and might topple over the edge into ridiculousness in the hands of any less gifted cast). I wrote down dozens of quotations as I watched, and will share examples to give you a taste of what I mean: at one point, Richard, goaded into fury by his whinging little brother John (who grows up into the tyrannical King John of the Robin Hood legends), whips out a dagger and chases John around Eleanor’s bedroom, seemingly intent on murdering his brother then and there. John screams out to his mother for help, exclaiming in apparent shock that Richard’s got a knife, to which his mother exasperatedly flings back, “of course he has a knife; he’s always got a knife: we ALL have knives! It’s 1183, and we’re barbarians!” At another moment, Eleanor’s reminiscing about her first husband, King Louis VII of France, and how she accompanied him on crusade—she recalls, “I dressed my maids as Amazons and rode bare-breasted halfway to Damascus. Louis had a seizure, and I damn near died of windburn… but the troops were dazzled.” Did I say it “borders on camp”? Maybe I should correct that: it takes place deep inside camp’s territory. The writing’s not just fireworks, though: sometimes there’s a quiet weight in it that reveals a character’s inner wisdom. Henry, at one point, defends his latest conniving by saying, “I’ve snapped and plotted all my life. There’s no other way to be alive, king, and fifty all at once.” Later, in a crisis, when Richard insists that whatever comes he won’t drop to his knees and beg, Geoffrey mocks his brother, saying, “You chivalric fool… as if the way one fell down mattered.” And Richard eyes Geoffrey, as if from a height his brother cannot touch, and replies, “When the fall is all there is, it matters.”

How is it that I can laugh at the soap opera of this maddening family, and a Christmas gathering in which the vast majority of the words flung between them are harsh, or cruel, or insincere, or condescending, or deceitful….and often more than one of those at a time? Again, I think the strength of the acting and the writing help: the worst insults carry the humor a little better when they’re delivered through really high art, I suspect. But I think it’s also that these people and their problems are so remote from me and mine: I can comprehend (after having played enough hours of Crusader Kings 3) a world in which people have these problems, betrothals lasting decades because they’re complicated feudal land arrangements, and marriages that are annulled decades after the fact but only if you effectively own the Pope, but that’s not the kind of thing I have to maneuver while eating Christmas dinner. Moreover, every single character on screen is just that—they are self-consciously characters. Eleanor and Henry are playing roles, roles that change at a moment’s notice depending on who’s in the room and what they want, and these children raised by them (Alais included) have learned to play the game too or else have learned how to benefit from it. Almost none of these words draw blood because the combatants are too scarred from decades of dueling, and everyone knows that this morning’s enemy may be your ally (or at least the mutual enemy of a more dangerous foe) by day’s end. Every bridge still up between these people was built for the sake of burning. If you watch this film, you’ll hear people saying some of the worst things they can think of—Eleanor and Henry, in particular, are gifted at this—and only you can know if that’s the kind of thing you can let yourself enjoy as a spectacle. I found that, more often than not, I could, and did.

I like, too, the way the movie gives us just enough to keep these characters straight: the three princes, for instance, are all introduced to us while fighting, in three quick, nearly wordless scenes. The economy of it from a screenwriting perspective is impressive. John (“Johnny” as Henry calls him) is dueling his indulgent father, who easily bests this teenager who seems to have no plan at all in life but to swing wildly, trusting that his father won’t hurt him really. Richard, on the other hand, we see at a joust, effortlessly tossing his opponent to the ground like Marshawn Lynch in Beast Mode, and then moving with a swift and apparent ruthless purpose to take his life before something interrupts: we perceive that Richard is a man of action, a fellow who likes to run directly ahead and trust his strength to carry him through obstacles. Geoffrey, then, we see perched high above a beach where his men are stationed secretly: he is never in any danger, and with a few swift hand signals to knights waiting below, he springs a trap he’d clearly set long in advance. He is cold and cunning, a strategist who if given time can get an advantage on his opponent, and who will never ever expose himself to risk. We’re only a handful of minutes in and we can already see the ways this family will find themselves at each other’s throats, with a kingdom up for grabs. As Henry himself later comments, “they may snap at me, and plot… and that makes them the kind of sons I want.” He loves the battles he fights with these young men, and he looks forward to them with a relish that suggests the energy of this conflict is what keeps him young, himself.

I know I haven’t touched on the holiday elements of the film much, but to be honest, despite the feast of Christmas being the ostensible reason for them all to be here (especially King Philip of France, and Henry’s prisoner queen, Eleanor), it comes up very little. It provides a context for some good japes—”What shall we hang, the holly, or each other?” made me laugh—and there are moments when both Henry and Eleanor make reference to religion, and sometimes even elements of Christmas itself, to clarify something about their purpose, but they’re momentary flashes at most. This is a story about power: “power is the only fact,” says Henry, though as the movie unfolds, we learn that there are other “facts” besides power that Henry struggles to understand. Among them is love, though it’s love in a lot of guises, few of them deeply sentimental. Eleanor’s seemingly deep attachment to Henry (much like his own strange, strained attachment to both Eleanor and Alais) is hard to parse: how much of it is performed for the sake of getting what she (or he) wants, and how much of it is honest? How real are Alais’s feelings, either—the girl seems passionate, but is it a passion for the crown, for the chance to bear sons to a king, or is it love for that aging king, himself? Surprisingly, maybe the sincerest expression of love we see in the whole film is an expression of same-sex affection: Richard the Lionheart, we learn in a couple of key scenes, is a man who loves another man, and as Richard is maybe the least subtle or deceitful of all the people in Chinon Castle this Christmas, I found it hard to interpret the things he says as being anything less than true, often painful feeling. For 1968, it was genuinely unexpected to encounter a gay character on screen, not to mention a character who in every other way seems to avoid the kind of stereotypes that would have then been commonly believed about gay men.

I could keep talking about this film for a long while—there are so many splashy scenes to comment on, so many lines of deliciously wicked repartee to quote—but I doubt that really serves you as a reader. If by now I’ve persuaded you to try the film, you’ll get more fun out of these things happening without my advance notice, and if you’re pretty sure it’s not for you, you should probably not be subjected further to my secondhand version. It’s probably just as polarizing a film as A Christmas Tale, which I wrote about earlier this year—shockingly similar, in fact, since in this film as in that French arthouse picture, we get a son asking his mother why she doesn’t love him, and we get to hear her complicated answer—but it’s just that somehow in this situation I “get” the film, in a way that I never “got” the other one. It’s not that this film is historically accurate, to be clear: none of this happened. These people existed, in one form or another, and they were almost certainly all schemers and plotters who played politics with each others’ lives, but they didn’t have a Christmas at Chinon Castle, in 1183 or at any other time. The resolution we get from the film’s final act is a resolution that deepens our understanding of these characters, but it’s not giving us much sense of what would happen next in a tumultuous era in medieval history. The truths that The Lion in Winter has to tell are truths about people, and the ways we lie to ourselves and each other to get what we think we want.

I Know That Face: Peter O’Toole, here the larger-than-life Henry II, appears later in his career as an elderly artist mentor named Glen in Thomas Kinkade’s Christmas Cottage, and lends his voice to Pantaloon, a toy soldier general, in 1990’s animated film, The Nutcracker Prince. John Castle, who in this film portrays the cold, scheming Prince Geoffrey, shows up in 2013 in one episode of the TV series A Ghost Story for Christmas as John Eldred. Nigel Stock, Henry II’s loyal servant William Marshal, plays Dr. Watson in a 1968 British TV episode of a Sherlock Holmes series, “The Blue Carbuncle,” which is the Holmes mystery set at Christmas (Star Wars fans may enjoy that Peter Cushing, Grand Moff Tarkin, plays the great detective in this episode). Anthony Hopkins, an electric presence in this early career-making role as Richard the Lionheart, at nearly the end of his career turns up as an aging and violent king—King Herod the Great—in the 2024 television movie Mary. He’s also an often-forgotten presence as the unseen narrator in the Jim Carrey How the Grinch Stole Christmas, which I’ll review here in the final days of this blog season. And of course blog readers will need little reminder of Katharine Hepburn’s other holiday performances, but in case you do, here she is obviously the Eleanor of Aquitaine, the most skillful of schemers, but we’ve seen her recently as Bunny Watson in 1957’s Desk Set, and as I remarked at the time, she also appears as Cornelia Beaumont in the 1994 TV movie One Christmas, which I kind of doubt will make it to FFTH anytime soon, and as Jo March in 1933’s Little Women, which I think stands a slightly better chance (though it’s undeniably less of a “holiday movie” per se).

That Takes Me Back: Haha, despite the jokes sometimes told by young people about my advancing age, no, I am not nostalgic for the High Middle Ages. I mean…given my personality, I suppose I kind of am. But I don’t have anything here I can point at, saying, “can you believe they’re chanting in plainsong, haha, remember the days before polyphonic harmony?”

I Understood That Reference: At one point, Eleanor slips into Alais’s room and hears her singing a carol—she praises the young woman’s singing as the only thing that keeps the castle from feeling “like Lent”, and goes on to comment that, growing up, she was so conscious of the earthly king’s power (as opposed to God’s) that when she was little she was never sure if Christmas was the birthday of the King of Heaven or of her Uncle Raymond. Shortly thereafter, Henry steps back inside the castle, having stood outside on the ramparts for a while and looked up at the great sea of stars in the night sky, and comments, “What eyes the wise men must have had, to see a new one in so many? I wonder, were there fewer stars then? It is a mystery.”

Holiday Vibes (2.5/10): As I mention above, we know it’s Christmas, but very little celebration occurs: I’d expected a Christmas mass or a big feast, but the events of the story either skip or preclude such gatherings, and as a result, though we do see wrapped presents and hear a little talk of the holiday, it’s not much at all to go on.

Actual Quality (8.5/10): This is a big, loud, well-acted and well-written royal soap opera. It’s probably about the best version of such a thing I can imagine, but it’s also not really high art. I found a lot of it fun, some of it confusing, and at least a few moments were pretty uncomfortable—especially when characters find ways to hurt one another that really do cut to the bone. I mostly loved the fireworks, though, and honestly, so do these characters. Eleanor and Henry are like bitter athletic rivals, who at the end of their careers can take some delight not just from their own remaining talent but from seeing it still burning in their ancient foe: game does not always respect game, maybe, but here, these competitors are happier when they’re getting as well as they give, for the sake of the sport.

Party Mood-Setter? It’s either too complicated to follow or too involving to watch: I don’t think I could leave it on the background of a gathering, though I guess maybe I could be decorating Christmas cookies while laughing at the banter between these spoiled princes and their seasoned warrior parents.

Plucked Heart Strings? Not even Eleanor herself, I think, has any idea how many of her tears are real, if any, and though Alais is badly treated by Henry, in time we see her true colors as a schemer, too. Maybe a person with a very particular romantic history could find themselves leaning in and feeling Eleanor’s attachment to Henry in spite of it all, but it doesn’t resonate for me. If I can feel it in any part of the film, I think it is in Richard, and what little we are shown of a love he knows must remain a secret.

Recommended Frequency: It’s a lot of fun, but there’s so little Christmas content here that I really think this is best left for whatever time of year you feel like picking it up, especially because it’s not just that we’re missing much in the way of references to the holiday, but because I feel like most of the thematic content runs counter to the best holiday narratives we’ve got to work with. It’s just out of step with the season, I feel like, though if you feel like trying it out once to see if a wintry medieval castle is close enough to the holiday spirit for you, I don’t think there’s any harm in it.

There doesn’t seem to be any free streaming option for watching The Lion in Winter, but you can rent it from all of the usual streaming services, it appears: pick your favorite. Or, of course, you can get it on disc: Barnes and Noble would be happy to sell you a copy, obviously. The easiest approach, though, might just be to trust your local public library—Worldcat promises that over two thousand libraries have a copy of this on the shelves, and my guess is that of all the “holiday” movies I review here, this one might not be in quite as high demand at this time of year. If ever you watch it, I hope you can get the entertainment out of it that I was able to find.